Travel

A Historical Gurdwara In Peshawar Is Allowed To Open Its Doors After Several Decades Since Partition

MIRZA KHURRAM SHAHZAD

As the inheritor of Gandhara, one of the world’s oldest civilisations, Peshawar is the living part of an ancient history. It is a city of the past, present and future.

It has suffered barbarism, tyranny and massacre at the hands of invaders as well as those who rose from its own soil. It has survived its past. It is surviving today and it yearns for a grand survival in the future.

Its traditions are alive, its bazaars abuzz and its buildings teeming with life. The interior of Peshawar is as vibrant as it always has been. The narrow streets, the old buildings, the wooden doors and balconies. The beards. The loud greetings in Pashto and Hindko.

Behind the dusty Grand Trunk Road, which snakes through the heart of Peshawar, connecting the ancient plains of the subcontinent with Central Asia, Russia and beyond, there is another world.

Then there are parts of this city which seem to be away from the boom of bombs, dead bodies, bullets and bigotry. A giant gate made of concrete and bricks in Hashtnagri opens to one such place. There are eateries, tailoring outlets, and shops that sell glittering jewellery for women who wear richly embroidered clothes.

There is a police station in an old building, perhaps built before Partition. Narrow, crowded streets; old, majestic houses; small but colourful shops overflowing with merchandise. One street leads to the Jogiwarra Mohalla (the place of jogis). Children run around here; the grownups walk.

Two men -- probably in their mid-60s -- with white beards sit at a cemented cradle. We ask them about the gurdwara; they express their ignorance.

Just then, another man, in his mid-40s, who is passing by signals towards a grand house in front of us. There it is.

There is a green ancient door of carved wood beneath the two-storey, yellowish brick house. Above the door is a cemented, curved mast. On the second storey, there are rows of windows.

The mast is plastered with torn fragments of election posters, a few bricks have fallen from the walls. The door is shut. There is a smaller door within the big door to enter and exit. We bend to get through the small door that leads to a passage with empty rooms on either side -- all in a highly insecure 19th-century building.

In front of the main door, the sun shines brightly down on the courtyard. On the right side of the entrance, there is a two-storey school where girls are memorising their lessons and also shouting at each other. On the left, a large portion of the complex containing several rooms, some damaged in the 2005 earthquake, awaits total collapse.

The December sunshine in the courtyard is pleasant. But better still is a charpoy, where an old woman sits with two young men in their thirties. They are savouring naan and chana for breakfast.

The woman, Ishrat Fatima, is 81 and has been living in the compound since 1954. She was the first head of the vocational training department in the province and established 14 technical education schools for girls. She rented a room in the gurdwara from the Evacuee Trust Property Board, which is looking after the building, and never vacated it.

She has family in England and Faisalabad. They have pleaded with her to join them but she doesn’t want to leave. The death of a dear nephew has dealt a severe blow and now she murmurs meaningless sentences, but is adamant to stay on in this building. Her white hair and flower-patterned dress, her room which is full of plastic bottles and other old items and mattress, all these are taken care of by a gurdwara caretaker.

In front of their charpoy, there are a couple of citrus fruit plants. And then there is the main building of the Gadara.

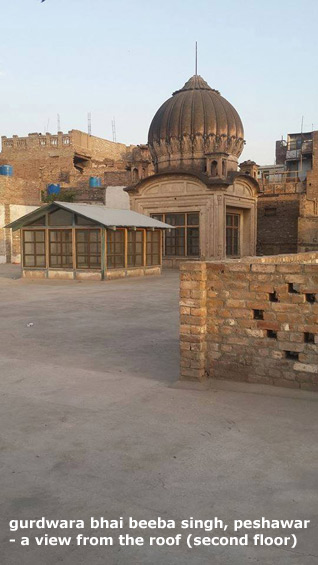

Its wooden balcony is half-broken. A signboard placed in one of the rooms reads, “Gurdwara Bhai Beeba Singh”.

Inside this room is a table and another charpoy over the brick floor; this is the office-cum-residence of the caretaker. Further left is the main worship hall, which is locked. The staff refuses to open it for us. But a while later, we manage to ‘sneak in’.

There, renovation material is spread everywhere. The walls, pillars, rooms and balconies are being painted in gold, off-white and black; the false ceilings are being renovated too.

“This historic Sikh gurdwara named after Bhai Beeba Singh, one of the beloved aides of our Tenth Master, Guru Gobind Singh, was closed at the time of Partition after the (forced) exodus of Sikhs,” says Sardar Suran Singh, adviser to the Pakhtunkhwa chief minister. “This is now being reopened after decades-long efforts by us. The Sikh community is really grateful to the federal and provincial governments and the local population for its reopening.

“The reopening of this place will send a positive message across the border where Modi is suppressing the minorities,” he adds.

Despite agreeing to the reopening of this gurdwara, locals still express concern about its activities.

“The gatherings in the gurdwara disturb the attached girls’ school and families in adjacent houses,” says Muhammad Ibrahim, a local social worker. “We agreed to its reopening after assurances that walls would be built around these buildings. The violation of the preconditions will lead us to protest.”

[Courtesy: Dawn. Edited for sikhchic.com]

January 5, 2015