Sports

Kabaddi in New Zealand

by GREG DIXON

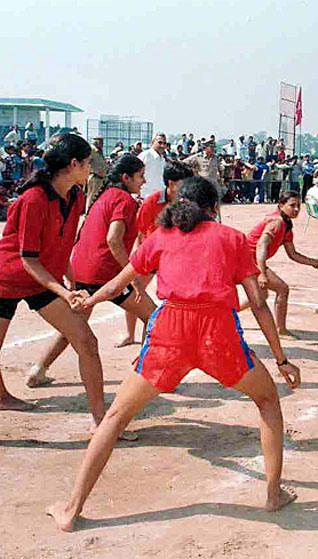

The raider moves in carefully, like a hunting cat. Slowly, he approaches his quarry - four men with linked arms - his own arms outstretched, waiting for his moment, his body taut. The hundreds watching seem to hold their breath, waiting, waiting for the moment.

All at once, the raider lunges, then touches one of the four and the real game is on. The raider flees for home, pursued by the man he's just tapped. The younger members of the crowd cheer as the raider is caught by his opponent and thrown to the ground. They briefly wrestle before the raider twists his body, regains his feet and sprints for safety. A whistle blows. Another point has been scored. And it all begins again.

There is nothing quite as strange as other people's games.

To an American from rural Mississippi, the game of cricket must appear a most queer sort of thing. To the Kamayura of the Amazon Basin, the game of rugby would no doubt seem a brutal, bizarre waste of eighty minutes and thirty people's time.

So it is that, to the eyes of the uninitiated, the game of kabaddi appears a most exotic affair - even here, in the far from exotic back blocks of Takanini, New Zealand, where light industrial warehouses press up against modest homes and damp paddocks.

It is a game that consists of two teams of twelve players. Each side possesses half a playing circle and alternates between defence and attack. However, its strangest detail, for those who have never seen it played before, is that no ball is involved.

But more later on the game. First food and prayers.

The kabaddi matches, which will run for a couple of hours on this late autumn Sunday, are light entertainment for the Sikh faithful who have come for weekly prayers and devotions at Takanini's Gurdwara.

The large white temple was built just over two years ago, on three and half hectares, and is something to behold. With three large and six small gold domes on its roof, it has a large golden entranceway - also with three gold domes - and contains two, large open floors, each half the size of a football pitch, one for eating and one for devotion.

More than a thousand people of all ages begin arriving in the late morning for the service that will run for a couple of hours, and the carpark out front is so full by 12.30, the traffic spills onto part of the grassy field where the kabaddi matches will be played.

After we remove our shoes and don headscarves, Manpreet Singh, secretary of the New Zealand Sikh Society, guides photographer Adrian Malloch and me into the temple's large downstairs langar hall, where mats are laid out in rows for sitting on while eating. There is no high table as it were; everyone from elders and priests to young children may sit where they want. It is the Sikh way that all are equal under God, and all are welcome.

There is a light snack offered before prayers begin, with lunch after. All the food is homemade, and though it is men who are toiling out in the large, commercial kitchen on the lower floor when I arrive, much work has been done earlier by wives, daughters and mothers.

We queue with Singh at the kitchen's large hatch for a little, stainless-steel bowl containing a small bread-like pakora, a spicy vegetable slice covered with a sweet, tangy sauce and, for dessert (though Singh eats his first), a bright orange deep-fried confection much like a soft fruit chew. Tea - sugary and milky and very, very hot - is also provided in stainless-steel tumblers.

After our bite, Singh takes us upstairs, where devotions have already begun. There are chandeliers and windows dressed in formal, mauve drapes. The thick carpet is covered by thin sheets of white cloth. Men and boys - some with traditional turbans, but many wearing headscarves like me - sit on the right.

Women and girls in bright salwar-kameezes - green, blue, red and orange - sit to the left. At the front of the room, a bearded, silent member of the congregation sits on a low platform, in front of which the Guru Granth Sahib, Sikhism's holy scripture, lies open.

It is surprisingly informal, compared to a church or mosque. People come and go. Kids run around. But most sit listening to the readings from the various speakers, who voice their devotions through a microphone from a lectern near the platform and priest.

The service is what has brought the faithful here, but Sunday congregations are also about family. "We're very social animals", 28-year-old Navtej Singh Randhawa tells me. "We're very collectivist". And the family that prays together also likes to play together.

The field of dreams was mown slowly by a bloke on a small ride-on mower, about half an hour before match time.

Varinder Singh Bains, who began playing the game in the early 1990s and will help ref the day's matches, supervises as a string is used to measure the diameter of the circle and the mower loops round clipping a thick flat ring of grass, before cutting it in two with a strip down its middle to delineate the field's halves. Young boys play and scrag and yell at each other in the middle of the circle as the makeshift field is completed. Excitement is building.

As lunch finishes inside the temple, people make their way outside, some bringing chairs with them, which they set up around the kabaddi ring. It is only when the congregation is outside that the clear distinction between the generations appears.

Many of the older men, as Sikh tradition demands, have full beards, uncut hair wrapped in turbans, and wear formal attire. The boys and young men are in fashion shirts, jeans and caps (one cap reads "Proud to be Punjabi").

Tradition seems stronger for the girls, who mostly dress like their mothers in bright, light suits of many colours.

Kabaddi is one of the world's oldest games and is known by various other names including chedugudu or hu-tu-tu in southern parts of India, hadudu (men) and chu-kit-kit (women) in eastern India, and kabaddi - which apparently derives from an Indian word meaning "holding of breath" - in northern India. The game is also played in Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Japan and Pakistan, with the Indian subcontinent's diaspora having taken the game even further afield to Canada, Britain, Australia and New Zealand.

Most who attend the Takanini gurdwara trace their roots back to (or originally came from) the Punjab in northern India. Indeed, the first Punjabis came to New Zealand well over 100 years ago; there are now close to 10,000 Punjabi Sikhs in New Zealand.

"Punjabis are a frontier people," Randhawa tells me. "I'd say, we were invaded more than twenty times. This [kabaddi] was seen as an extension of us being a warrior people. This is the only game Punjabi Sikhs support unreservedly because it's one on one".

The first New Zealand tournament was held in Hamilton in 1990, and there are now several tournaments a year and eight clubs around the country. Because today's games are simple friendlies, there are just three makeshift teams playing in the afternoon's round robin, with some of the players ring-ins.

The gurdwara held a large, formal tournament a month earlier, to mark the second anniversary of its opening and about thirty professional players, thanks to sponsorship from local Sikhs, came from India. One even came from Italy.

On the international pro circuit, which includes India, Canada and Britain, the best players can earn something like $100,000 a year. New Zealand is now plugging into these players, because sponsoring kabaddi teams is fast becoming a big deal for local Sikh businessmen.

"Funds are no problem, we are an affluent community", says Randhawa. "So, what's starting to happen now is a lot of senior members of the community field a team and there's a lot of pride riding on that. They've got to show that, among their community, they have arrived.

"It's a positive thing. Instead of putting money into fuelling wars, we're putting money into this and into our next generation. And locals come because they see it as keeping their culture alive".

The game is fast, very fast.

Kabaddi, or at least this version, consists of twenty-minute halves with a break of five minutes in between. The two teams form up in their halves. A small "gate" is marked on the line bisecting the circle. A raider must leave and return from his raid through this gate, and the teams alternate in sending a raider across to the other's territory.

These days, the raid is timed; in the past, the raider was supposed to take one breath and prove this by chanting, "Kabaddi, kabaddi, kabaddi..." during the attack. Now the raider has exactly thirty seconds to cross into enemy territory, touch one of the four defenders and return to his own half. Success means a point. The most points at the end of forty minutes mean a win.

To an outsider, the game appears to combine the speed, strength and elusiveness demanded by rugby's back play with all-out wrestling. It certainly can be brutal. If a raider is caught by a defender, it can become a life-and-death-like struggle, as the former attempts to escape, while the latter struggles to hold his opponent until the whistle to mark the end of the thirty seconds is blown.

Pain is borne in silence. One bloke has his thumb dislocated and pulled back into place without uttering a sound, though his face said enough. The rate of injuries is high compared to other sports, says Randhawa, who no longer plays, because his wife was too concerned about him.

"It's a very high impact game. But once you've played, you can't get away. It's a rush".

[Courtesy: Metro, Auckland]

Image on Home Page: detail from painting by Sukhpreet Singh, from "Games We Play" - 2007 Calendar by The Sikh Foundation International, Palo Alto, California, U.S.A.

A short video called "Sikh and Destroy" has been produced by Anthony Ferraro and Matthew Sultan. Duration: 00:06:50.

Please click here to view it: http://www.current.tv/pods/sport/PD06595

Conversation about this article

1: D.J.Singh (U.S.A.), August 31, 2007, 8:54 PM.

The thrill of a sport like kabaddi lies in defeating the adversary against all odds. The bliss in a religion like Sikhism lies in maintaining faith against all odds. Sports and religion are different, yet so similar. Sava lakh se ek ladaaoon....

2: Harinder (Mohali, Punjab, India), September 01, 2007, 4:03 PM.

Great to see Punjabi sports, music, culture spreading around the world. Our ancestors were original in inventing a novel game called Kabaddi. Wish our young men and women today will continue the innovative spirit and, who knows, maybe invent another game of their own!

3: Jas (California, U.S.A.), September 07, 2007, 12:47 PM.

Great Sport. It deserves more than what we are offering to date.

4: Daljit Singh (India), September 09, 2007, 9:16 AM.

I want to commend the Sikhs of New Zealand for their phenomenal work in carrying the torch forward.

5: Ghazal (Tehran, Iran), February 10, 2013, 3:48 PM.

How can I connect with the Kabaddi Federation in New Zealand? Any contact info?