Partition

The Sikhs of Potohar

Tales of Haripur, Part IV

by Dr. Bhai HARBANS LAL

In 1946, Hindu-Muslim riots started in Bihar [a state in eastern India, adjacent to Bengal]. It was expected that they would be replicated in short shrift in the Northwestern provinces. This meant that the Haripur inhabitants could expect the same.

It didn't take long for bad news to pour in. There was daily and hourly news about riots, assaults, stabbing, looting and murder somewhere or the other in the Hazara area. It was no longer safe to live even in our ancestral town of Haripur. The situation in the surrounding villages was even worse. Sikh and Hindu families were moving to Haripur for shelter with their relatives and friends.

The situation concerning students was also precarious and rather peculiar. Sikh and Hindu students could not walk to school for fear of being killed en route. On the other hand, they could not leave town, because that would put their getting their imminent high school degrees at risk, by jeopardising the completion of the school year in their regular school. Even then, many students decided to leave school and accompany their parents to somewhere across the new border to safety.

When the time for the final High School examination arrived, most of them had already decided to move out of Haripur. A few who were left would not go to the school to take the final examination.

I was afraid that without taking the final examination there would not be any record available for my attendance for the full term in that school. In that case, I would have to spend at least one more year in school, once peace prevailed.

That would mean missing at least a year in starting my college, a probability that I could not accept. Thus, along with Manmohan Singh Kohli, I decided to stay on in our home in Haripur until the examination day. We started studying at home and risked our lives to walk to the examination hall on the given day.

We were relieved somewhat when the army offered us an escort to and fro between our home and the examination hall. We accepted the offer, albeit reluctantly, and proceeded to the school. Upon reaching the hall, to our utter amazement, we found it virtually deserted.

The seats were only scantily filled. None of the non-Muslim students - except two of us, Mohan and I - had shown up.

As soon as the examination papers were distributed, we heard a commotion in the hall. One examinee had pulled out a revolver, another a dagger, and they had placed them on their desks in front of them, for all to see. Having done so, they then pulled out their text books and notes, and spread them out on their desks. While freely consulting them - a definite no-no during an exam - they also freely consulted with their friends to help them in answering the exam questions.

Understandably, the supervisors turned their backs in fear of being shot. Later, we heard that two of our friends had been stabbed earlier while making their way to the same examination hall.

With prayers on my lips, I finished the examination. When the results were announced - several months later, when I was safe in India - I was delighted to see that I had done very well. My high grades enabled me to enter college for my pre-medical education.

* * * * *

The deep commitment of the Sikh inhabitants of Haripur Hazara to the Sikh way of life was known far and wide; the reputation dated back to the time of the Sikh kingdom of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Sikh scholars, raagis, parcharaks, as well politicians from all over Sikhdom were frequent visitors, and graced our congregations. So were Sikhs from the West ... from as far as Afghanistan.

In fact the Sikh inhabitants of this area were important components of the Potohari segment of the panth.

Potohar Sikhs, in general, were held in high esteem among the Sikh nation for their deep commitment to the Sikh ethos and flair. The town of Haripur and its surroundings were a part and parcel of the Potohar region of the North West Frontier Province within the sub-continent. Rawalpindi was the nearest large city to Haripur. As such, the Sikhs of Haripur and its surroundings were closely knit and connected to the Sikhs of Rawalpindi.

Rawalpindi dates back to 1493 A.D., when it was given its name by Jhanda Khan, a chief of the Ghakkhars. The Ghakkhars were defeated by the Sikhs in 1765 - a significant event that attracted many Sikh traders to the area. They brought with them prosperity and the atmosphere of kinship, peace and neighborly love among all inhabitants, irrespective of their religious or ethnic background.

In 1849, the British took Rawalpindi away from the Sikh rulers but the Sikh populations continued to excel in trade and prosperity.

The Sikhs of Potohar region had made big strides in all walks of life. They exhibited the highest literacy rate and higher levels in education. Similarly, their employment ratio was higher than their neighbors. Partition of Punjab and India scattered this cultural and business groups of Sikhs, leading them to be forgotten as a distinct group. It is precisely for this one overriding reason that I wish to record my memories of this distinctive group of Sikhs in my memoirs.

Potohar Sikhs shared many cultural characteristics and features with the Muslims of Potohar. Resemblance of physical features is understandably apparent because they had lived together for centuries, and had common ancestors. Some of them continued to live together until the recent past.

One of the most striking resemblances was the Potohari dialect of the Punjabi language, both written and spoken. The Potohari language is enriched with many Farsi (Persian) and old Sanskrit derivatives. Besides, the native traditional Potohar dress makes them strikingly distinct in appearance from the other ethnic communities on the subcontinent.

A large number of the Potoharis are Pashtoons. There seems to be a common identity of features and likeness between them and the Sikhs. Pride, warmth, courage, hospitality, openness, boldness, simplicity and, above all, personal honesty, were some of the traits that one could find common between these two communities.

Among the Potohari Sikhs of Hazara, most of them were sehajdhari Sikhs. This segment of the community, unlike the khande-di-pahul-dhari Sikhs did not distinguish themselves with unshorn hair. The unshorn hair generally is a distinctive feature of Sikhs who have taken on a greater degree of discipline of the faith.

Hazara's Potohari inhabitants were inspired to be Sikhs by local and visiting Sikh raagis and exegists. Some of the sehajdhari Sikhs accepted khande-di-pahul to become Khalsa Sikhs during the period of 1910-1945 through the efforts of Sant Baba Jiwan Singh and later Baba Prem Singh Niroliwale, Sant Attar Singh and their generation of Sikh exponents.

All Sikhs had great esteem for the Khalsa initiation by khande-de-pahul. Every Vaisakhi, the initiation ceremony would take place with great enthusiasm and fanfare. Some Sikhs from the neighboring villages would come to take Amrit. However, there was a difference in the level of commitment then, compared to what we see today.

A saintly figure would come to the town a few weeks before Vaiskahi to initiate the faithful. He would spend weeks in interviewing the faithful who travelled from distant villages to take the vows.

Each interview was to determine if the seeker was qualified. He or she was interrogated regarding their life-ethics. Did they ever tell a lie in the past year? Did they ever miss reciting of the five daily banis? Had they committed sacrilege of any of the kakkaars? If they passed those tests, only then were they then declared ready to be admitted to the fold.

There were a few who would qualify every year. Others were given another year to practice the “rehat” before they could try again. Thus, there were few but thoroughly committed seekers to join the Khalsa fold. It is only because of this prior coaching that no one was ever known to not practice the disciplined Khalsa life after the Amrit baptism. I had not known any Khalsa Sikh in town who ever trimmed his/herhair, not do the daily nit-nem or to ever tell lie for any reason whatsoever, or any other kind of

crossing the line.

It was this commitment of the initiated Sikhs that brought the elevated reputation of the Sikhs among the neighboring communities, including the ruling British. Moreover, sehajdhari Sikhs and the Khalsa Sikhs lived close to each other and respected each other as parts of the same Sikh community.

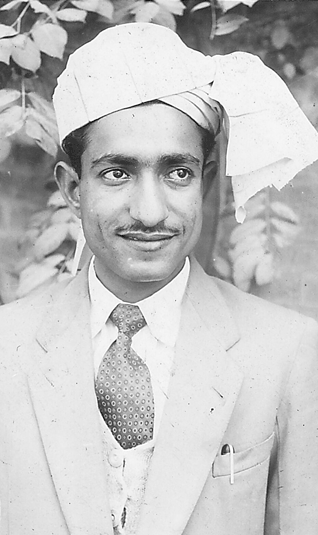

Both sehajdhari and keshadhari Sikhs wore the mashedi silk turban, commonly known as puggri or turban, which was also worn by the Pathans and Afghans. Sehajdhari Sikhs wore their turban around a supportive kula or a round shaped hat. The kula is a kind of soft cap made of a thick cloth or compressed paper covered by cloth, or both. It was used by non-Muslims and was usually embroidered with silk. It served the purpose of holding the turban in place ... exactly what the joorrah did for the keshadhari Sikh.

The tail of the turban worn by a sehajdhari Sikh would hang loosely down the back of the neck. Sikh men wore the Kandhari vest, apparel consisting of a long loose shirt and salwar or pathani pants, and the gold-threaded jutti or khusa (Pothohari shoe). A long shirt was worn outside the trousers, hanging down almost to the knees.

The unique costume and language were the typical signature of the Potohar people of yesteryear - they made them conspicuous amongst all others on the sub-continent. Some older folks from ‘Hazara-Pindi-Peshawar’ region still wear such clothes that we see occasionally in parts of Punjab and Delhi.

When I migrated to U.S.A., I specifically brought with me a set of Potohari clothes, including a kula-puggri combination, to be worn on special occasions.

In Haripur, Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs lived quite amicably. There was not the slightest semblance of any animosity until the time of Partition. The places of worship or those related to the respective religions were venerated by all. The people usually participated in all the major festivals of these three main religions that, inter alia, included Guru Nanak’s Birthday, Diwali and Eid. This demonstration of cordiality and homogeneity formed part of the Potohari culture that blended well with the perceptions and practices of the Sikhs.

Before the Partition, the Indian National Congress Party enjoyed a majority for several years in the State legislature in NWFP. Dr. Khan Sahib, a prominent member of INC, was the Chief Minister. Dr. Khan was a strong proponent and preacher of communal harmony and was therefore respected by Muslims, Sikhs and Hindus alike. His followers and party activists were known as “Khudaa-i Khidmatgars” meaning “The Servants of God.”

Continued next Wednesday, August 24 ... Part V ...

August 18, 2011

Conversation about this article

1: Gurpreet Singh (New Delhi, India), August 18, 2011, 10:55 AM.

This is a great series, taking us through the by-lanes once traveled by our ancestors. Is there a consolidated version of Dr. Bhai Harbans Lal's memoirs? Also, a link to the previous parts? [EDITOR: You can access the previous chapters in the PARTITION section of sikhchic.com anytime.]

2: Daljit Singh (Surrey, British Columbia, Canada), August 18, 2011, 12:21 PM.

This brings back a lot of memories of stories being told by my parents. My mother was born and raised in Rawalpindi and my entire 'naanke' are from the Potohar region. To this day, I admire the Sikhi in people from this region, whether Sehajdhari or in Keshadhari form. It was their indomitable spirit that, even after losing all material possessions, kin and friends, and being tagged with refugee labels - 25 to 30 years after partition, they were prospering in all parts of the world. My salute to them!

3: Gurnek (United Kingdom), August 19, 2011, 8:54 AM.

Indeed. a great article. i feel a lot of our woes were exacerbated by the sidelining of this community and other West Punjabis after Partition and the subsequent rise of those who were living in eastern Punjab.

4: Harpreet Singh (Delhi, India), August 22, 2011, 4:18 PM.

It is hard to imagine for people today that such communal amity had ever existed amongst different communities. All we have seen in India in recent memory are communal riots, tales of dirty politics and mindless violence, atrocities on innocent Sikh youth and others, over and over again - their only crime being their religion, or the region they hail from. Will we ever see a time without such anarchy and mayhem again? Leaders of all faiths must be willing to do this and avoid unnecessary conflicts.

5: Jasvinder Singh Obhan (Bangalore, India), November 06, 2011, 2:45 AM.

My parents and grand parents were from Village Saria Niyamat Khan, City Haripur and Zilla Hazara. Do you have information or memories re this particular village, please?

6: Jagmohan Singh Rana (Delhi, India), October 10, 2013, 2:49 AM.

Indeed very informative. I would like to know about Duberan / Diberni, the native place my parents ... if anyone has any information, please.

7: Aziz (Haripur, Hazara, Pakistan), November 09, 2013, 6:02 AM.

The elder people still remember and recall good memories. Kindly send the particulars of your elders. We will send you the pictures of your house and village.

8: Nadeem (Haripur, Hazara, Pakistan), January 15, 2016, 8:13 AM.

Any Sikh from Haripur Hazara who wants pictures of their family's former home(s) can contact me through this site.

9: Musa Khan (London, England), February 09, 2016, 2:16 PM.

As a native of Potohar, to be specific, of Gujar Khan, I have many fond memories of the area. One striking part of our culture is our dialect and our traditions, which are quite different from southern Punjab. I have heard some stories from my grandfather about pre-47 Gujar Khan but not enough as he has passed away. If there are any Sikhs who had family in this area, I would love to know your story. I feel it is very important that we do not lose these memories to time.