Partition

Partition Of Punjab:

A Love Story

SOUTIK BISWAS

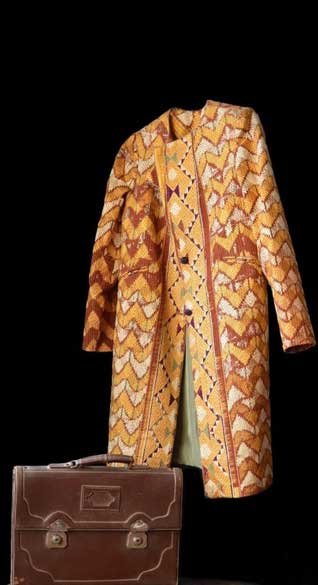

These are two unremarkable, ordinary items: a traditional embroidered jacket and a drab, brown leather briefcase.

They belonged to a man and a woman who lived in Punjab during Britain’s occupation of the subcontinent. They had been introduced to each other by their parents and were to be engaged when violence broke out in 1947.

The troubled subcontinent was lurching towards a bloody partition of, inter alia, Punjab as it split into the new independent nations of India and Pakistan. Communal violence erupted, leaving more than a million people dead and displacing tens of millions.

Punjab was divided - western, mostly Muslim parts went to a newly created Pakistan and eastern, mainly Sikh and Hindu parts, went to a newly created India. The newly-engaged man and woman were Sikhs living in what is now Pakistan.

The jacket and the briefcase were their most valuable possessions as they fled their homes to escape death as communities butchered each other in a prolonged frenzy of religious rioting.

Three of Bhagwan Singh Maini's brothers had already been slaughtered in the violence, so the 30-year-old man stuffed his certificates and property claims in the fraying briefcase and fled his home in Mianwali.

More than 250km (155 miles) away, in Gujranwala, Pritam Kaur's family slipped out of their house and put her on a train to Amritsar.

Pritam Kaur, 22, travelled across the blood-stained border with her two-year-old brother on her lap. In her bag was her most precious possession, the phulkari (embroidered) jacket, a reminder of happier days.

Torn apart by what turned out to be the greatest mass migration - or transfer of population - in human history, the two landed up in teeming refugee camps that dotted Amritsar city. They were among the more than 15 million people who had crossed the new borders.

One day, in the food line, a miracle happened.

Both Bhagwan Singh and Pritam Kaur had joined the queue of bedraggled, hungry refugees. There, they met again.

LIFE, LOST AND FOUND

"They exchanged notes about their tragedies, wondering if it was destiny that had brought them together once more. Their families, or whatever was left of them, also reunited in due course," says Cookie Maini, daughter-in-law of Bhagwan Singh.

In March 1948, the two got married. It was an austere ceremony; both families were struggling to pick up the pieces.

Pritam wore her favourite jacket. Bhagwan got together his certificates and papers from his briefcase to start a new life: he joined the judicial service in Punjab, got a small house in compensation and moved to Ludhiana with Pritam.

The couple had two children, who both served as civil servants. Bhagwan died some 30 years ago; Pritam died in 2002.

"The jacket and the briefcase," says Ms Maini, "are testimony to the life they lost and found together."

They now survive as two of the most valuable possessions of a fledgling Partition Museum, which opened in Amritsar, Punjab, in October.

By early next year, the museum, housed in the magnificent and restored Town Hall, will showcase photographs, letters, audio-recordings, belongings of refugees, official documents and maps and rare newspaper clippings relating to the event.

"This will be the most comprehensive archive on the partition, and the only museum of its kind in the world," says Mallika Ahluwalia, chief executive officer of the two-floor, 17,000 sq ft Partition Museum.

There are the stark black-and-white pictures of the never-ending caravan of Sikh, Hindu and Muslim refugees, trudging wearily to what will be their new homes. Bullock carts overflow with sparse belongings and withered humans. Millions of refugees were on the move; one single convoy was reported to have stretched for 10 miles.

Trains awash with the blood of murdered refugees steamed across the new borders. Too few police and soldiers were deployed to check the ensuing violence. Historian Ramachandra Guha says the "protection of British lives was made the first priority", while the rest of the country was abandoned by the fleeing occupiers. Women wore the brunt of the violence: tens of thousands were abducted, though many were eventually recovered.

Tent cities sprouted all over the country to house the displaced farmers, artisans, government workers, traders and labourers. By 1950, there were some 200,000 refugees in squatter colonies in the eastern city of Calcutta alone.

Refugees abandoned millions of hectares of their own farm land and many received scant compensation: a widow who lost her husband's 11,500 acres of land in two districts which went to Pakistan was given 835 acres in a village in Indian Punjab.

Months after the event, the bloodbath was still continuing. The front page of a Punjab-based newspaper in October paints a picture of utter despair and anarchy in the state.

Armed mobs were attacking villages, towns were plunged into darkness, there is a story about the "moon coming to the rescue of millions" after a power outage as well as accounts of a cholera outbreak , floods and details about millions of people stranded in refugee camps awaiting evacuation.

"Life here continues to be nightmarish," wrote India's first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in October 1947. "Everything seems to have gone awry".

Until you hear - and see evidence - of stories of hope and redemption, of lives lost and recovered, as in case of Bhagwan Singh Maini and Pritam Kaur.

With these stories and more, the museum in Amritsar hopes to remind people of an event which author Sunil Khilnani described as "the unspeakable sadness at the heart of the idea of India".

[Courtesy: BBC News. Edited for sikhchic.com]

March 27, 2017