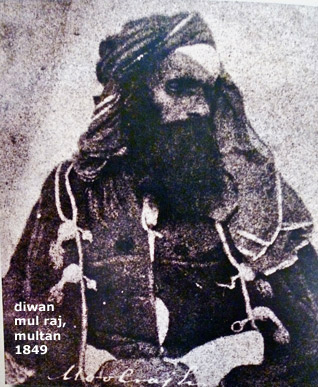

Image below, first from bottom: Diwan Mul Raj's photo was taken while he was in British custody in Lahore.

History

A Pride of Lions:

A Display on War & Sikhs

MELISSA VAN DER KLUGT

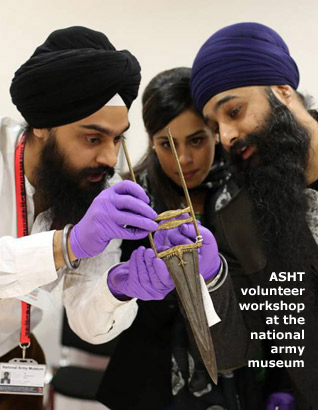

On regular Saturdays in recent months, casual observers in Chelsea, one of London's most renowned areas, may have noticed groups of Sikhs gathering at Sloane Square tube station and making their way to the National Army Museum. Their mission , as part of a pioneering project between the museum and the Anglo Sikh Heritage Trail, was to offer a new perspective on collections which had rarely been in the public eye. The following article in The Times reveals the whole story:

A long-lost cache of Victorian photographs has opened a window on Sikh military history

A series of photographs taken in India by an off-duty Scottish surgeon on the eve of war and now being dusted off in a Chelsea museum are being used to re-examine the beginnings of the 150-year relationship between Sikhs and the British Army.

John McCosh was stationed in Lahore in 1848 with an East India Company regiment and fought in the second Anglo-Sikh war in which the Sikh empire that had stretched from modern-day Afghanistan, across modern-day Pakistan, all the way to the suburbs of Delhi, fell to British rule.

Although initially disarmed, Sikh soldiers, much admired by their British counterparts, were quickly recruited into East India ompany units and fought in conflicts from the Indian Mutiny to the Afghan wars.

In one famous Victorian battle, just 21 Sikhs fought to the death against ten thousand Afghans.

Hundreds of thousands of Sikhs fought for the Allies around the world in the First and Second World Wars.

“Many Sikhs in Britain have relatives who served in these wars,” says Jasdeep Singh of The National Army Museum, who works in conjunction with The Anglo Sikh Heritage Trail which promotes shared inheritance between Sikhs and the UK. “The general consensus is one of pride.”

However, McCosh’s photographs and other rare artefacts in the large archive relating to Sikh military history at the National Army Museum in London have not been seen by anyone from the Sikh community.

This summer a group of volunteers has begun a project to re-examine Sikh contributions to Britain’s Armed Forces and the museum’s material, often poorly labelled or understood by its Victorian collectors.

McCosh’s portraits are a glimpse of 19th-century Punjab and its capital, Lahore, where the Sikh faith was born and flourished, and its people and rulers on the cusp of war. Among McCosh's subjects was the 10-year-old Maharaja Duleep Singh, the last Emperor of Punjab whose father Ranjit Singh, the Lion of Punjab, was the founder of the Sikh Empire.

Ranjit Singh rallied the empire’s warriors against neighbouring Afghan, Mughal and European invaders, carved out new territory and built a reputation as a fierce military opponent, developing his own armoury and cannons. His sword (shamshir), donated by the family of a British officer who served in Punjab, is among the museum’s prized artefacts, along with a fortress turban (dastar boonga), worn by warrior Nihang Sikhs to hold their daggers and protect them in battle.

After Ranjit Singh’s death in 1839, his kingdom fell into disarray through, inter alia, British machinations.

The rare photograph of the young Duleep, who took the throne aged 7, backed by the British, hints at his sad fate. After the annexation of the Sikh empire the boy was placed out of the way in the care of a British guardian in a quiet backwater on the Ganges and given, while still of tender and impressionable age, a 'Christian education'. 1n 1854 he came to Britain where he was embraced as an exotic figure by Victorian society, living for a time in a Scottish castle where he was known as the “Black Prince of Perthshire” and enjoying the attentions of the Queen with whom he went to stay at Osborne House.

However, in later life, disillusioned with his treatment by the British, he reconverted to Sikhism and was involved in several unsuccessful attempts to regain his kingdom. He was buried in a Suffolk churchyard.

McCosh’s images have an extra significance: they are the earliest known photographs of Sikhs.

“They are a window for us on the dress and architecture of the time,” says Jasdeep. Punjab was partitioned between India and Pakistan amid much bloodshed in 1947 and millions of Sikhs were forced to flee, leaving behind their homes and history in places like Lahore, where Ranjit Singh had once lavished money on arts and building and presided over booming trade and wealth.

The photographs are also some of the earliest examples of war photography.

The success of the National Army Museum’s workshops at gurdwaras from Hounslow to Birmingham to re-examine its 19th-century collection means the project will be extended for several years.

Jasdeep Singh of The National Army Museum, along with the volunteers at the Anglo Sikh Heritage Trail, will begin the enormous task of exploring archive material relating to Sikhs’ contributions to the First World War in time for its centenary next year.

[Courtesy: The Times. Edited for sikhchic.com]

August 26, 2013