1984

Punjab and India Need Paramjit Kaur Khalra’s Voice in Parliament

PREETIKA NANDA

In April 2017, the Indian Academy of Fine Arts in Amritsar, Punjab, was transformed into a People’s Tribunal. As I sat beside each person, usually an elder, they would slowly look for a small pocket in their salwar kameez, and bring out a passport-sized photo of a loved one, a phone number on a scrap of paper. Others carefully took out folders with ruined edges, from plastic bags creased like the skin on their hands.

For the 700 people present that day, the action of presenting those papers, photos, telegrams and petitions was repeated daily. All of them were kin of Punjab’s extra-judicially executed.

It was then that I met Bibi Paramjit Kaur Khalra, wife of the murdered human-rights defender Jaswant Singh Khalra. Powerful yet deeply humble, Paramjit’s image is etched in my mind. Her hands stayed folded gracefully as she thanked us for organising the Tribunal.

The Independent People’s Tribunal aimed to present some preliminary findings of the Punjab Documentation and Advocacy Project. The PDAP had been operating for almost nine years. The families present had spent much longer, waiting for loved ones who never returned.

Their absence was palpable in the memorabilia their relatives had preserved, also in testimonies, records – and even in the seeming banality of who sat beside whom.

Families of those abducted or killed on the same day sat together. They explained this after giving me their initial information. I would then mark a square bracket beside the victims’ names and write, “killed together”. In retrospect, I understood their attachment to a collective past and a frail hope for closure.

A one-woman pillar of memory

Paramjit Kaur Khalra had stood by many such families. For two decades, she has been committed to the unseen families of Punjab, making the ‘Khalra’ name almost a metaphor for resilience, truth and sacrifice.

Now she is a Lok Sabha candidate, from Khadur Sahib.

Her husband, Jaswant Singh, was a human-rights pioneer who systematically investigated links between enforced disappearances and illegal cremations. After his friend Dara Singh’s death in 1994, Jaswant Singh uncovered that the Punjab Police had killed him in an extrajudicial encounter, and cremated his body at the Durgiana Mandir, labelling it “unidentified and unclaimed”.

Seeking an independent investigation, he approached the Punjab and Haryana High Courts with a Public Interest Litigation, which was dismissed.

Jaswant Singh’s perseverance against growing hostility from the state led him to travel across Punjab. He conducted interviews with attendants of cremation grounds, and uncovered how, at times, multiple bodies were cremated on a single pyre, how doctors dispensed with post-mortems, how families of the victims had similar stories of abductions and eliminations. Jaswant Singh’s work laid the blueprint for documenting mass-executions in Punjab.

On September 6, 1995, Jaswant Singh was washing his car outside his home in Kabir Park, Amritsar, when he was abducted by the Punjab Police.

He was never seen again.

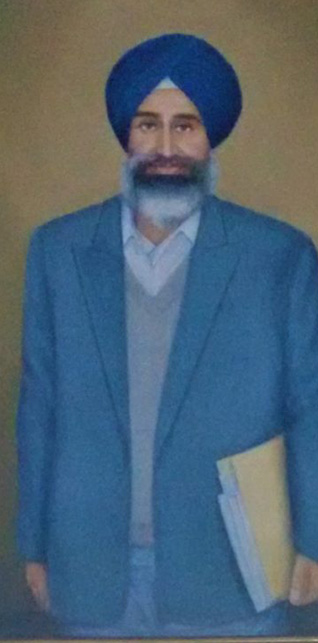

In the summer of 2018, when I visited his home, it was hard to not be affected by his visceral presence. On one wall is a portrait of him, in a blue blazer and a turban, with calm yet determined eyes, carrying documents in a khaki covered file.

Jaswant Singh was only ever armed with documents: collated by scrutinising, say, the firewood purchase registers maintained by Municipal Committees. Records that were the moorings of a bureaucratic state creating an “aura of legal operation” around overtly illegal (and violent) acts.

Paramjit Kaur’s habeas corpus petition to find her husband culminated in two sets of enquires by the CBI: one into Jaswant Singh’s abduction, and one into police abductions and mass secret cremations in Punjab.

After a long legal battle – filled with cover-ups, intimidation, disinformation campaigns, false charges of rape against witnesses – six police officials were convicted of Jaswant Singh’s murder and abduction in 2005.

Jaswant Singh had been tortured in custody, then shot dead during interrogation on October 28, 1995. His body was disposed of in the Harike canal, like the many others killed and disposed of in Punjab’s ‘watery graves’.

Paramjit refused to be silenced. With Jaswant Singh’s friends, she formed the Khalra Mission Organisation in 1995 and reignited the struggle to keep Punjab’s “disappeared” visible and relevant.

She continued to work as a librarian at the Guru Nanak University, Amritsar, and to parent her two children. Her personal life blended with filing claim-forms to the National Human Rights Commission, organising memorial meetings, following up on cases in courts, preserving newspaper archives.

The labour of memory came entangled with trauma. Every case brought up memories of her own struggle.

Bureaucracy vs memory

In December 1996, the Supreme Court entrusted the NHRC to redress all matters related to the Punjab mass-cremations case. The sixteen-year proceedings at the NHRC revolved around “procedural lapses” in mass cremations in just one district of Punjab.

No victim or survivor testimonies were heard through all those years, rendering their suffering invisible.

While establishing 2095 illegal mass-cremations by security forces in Amritsar alone, the circumstances – whether genuine encounters, extra-judicial executions or custodial killings – that led to the cremations were not investigated.

Instead, the NHRC categorically refused to fix responsibility, helping perpetrators to remain invisible as well.

On June 9, 2017, Paramjit was in the village of Behla in Amritsar for the annual memorial meeting of the Behla kaand. On June 9, 1992, six civilians were killed after they were used as human shields in an encounter. The operation was led by Khubi Ram, security advisor to the current chief minister, Amarinder Singh. Police officials covered up the killings by claiming to have killed nine terrorists.

Paramjit Kaur demanded action against culpable police officers who still hold high positions in power. Victims and survivors’ families expressed solidarity with Farooq Ahmed Dar and called the infamous incident in Kashmir a war crime. The villagers recollected their memories of a 34-hour long encounter during which they were used as human shields. They name police officials responsible for the operation. Importantly, they name the six civilians who were killed. This was crucial, since the records at the NHRC said the six were unclaimed and unidentified.

Punjab was just the beginning

Paramjit says: “A lot of people talk about ‘new normals’ in the country, but these were set in Punjab many years ago — in terms of mass disappearances and the silence of civil society.”

Verne Harris, once the head of Archive and Dialogue at the Nelson Mandela Foundation, wrote that the documentation of mass violence “is open to the future and to every “other”’.

The location of violence and upheaval changes, but the replication of patterns of abuse and impunity helps us understand the real nature of a polity.

The Manipur government is yet to grant sanction to the CBI to prosecute fake encounter cases. The case, which led the Supreme Court to order a probe into at least 1,528 alleged extra-judicial killings, remains stalled.

Similarly, between 2001-2018, the Ministry of Defence denied sanction to 47 out of 50 cases relating to alleged custodial killing, rape, murder and torture of civilians by security forces. All these instances mirror the 16-year-old stay on trial for 37 cases clubbed together under Devinder Singh & Others vs. State of Punjab, only lifted by the Supreme Court of India in 2016.

The legacy of Paramjit Kaur is a repertoire of lessons. She is a human-rights crusader. Her life is a testament to bravery, perseverance and grace in the face of an intransigent judiciary, apathetic civil society and a pliant media. She continues to believe in the people and democratic institutions.

We need her voice in the Indian parliament.

The author has worked with the Punjab Documentation and Advocacy Project and researches Violence, Memory and Resistance in ‘post-conflict’ Punjab.

Courtesy: The Wire. Edited for sikhchic.com.

May 15, 2019