Columnists

I See No Stranger:

Early Sikh Art and Devotion

Reviewed by Laurie Bolger

I SEE NO STRANGER: EARLY SIKH ART AND DEVOTION

by B.N. Goswamy and Caron Smith, Rubin Museum of Art, New York, in association with Mapin Publishing, 2006.

214 pages. Price: $ 39.95

This catalogue was published in conjunction with the exhibition, "I See No Stranger: Early Sikh Art and Devotion," held at the Rubin Museum of Art in New York City from September 18, 2006 to January 29, 2007. It was authored by the exhibit's joint curators: Dr. B.N. Goswamy, Professor Emeritus at Panjab University and Dr. Caron Smith, the Rubin Museum's Deputy Director and Chief Curator.

This exhibition is the first of its kind in New York City, where the largest population of the half a million Sikhs in the United States live. Unlike earlier shows in San Francisco, Toronto, London and New Delhi, and the ongoing installation in Washington, D.C.'s Smithsonian Institution, which all displayed a broad and comprehensive view of Sikh art and culture, it focuses closely on what its co-curators term "visual reflections of fundamental beliefs."

Despite Sikhi's place as the world's fifth largest religion, with over 24 million adherents worldwide, even its most basic beliefs -- the oneness of God and the equality of humankind -- remain largely shrouded in mystery and misconception here in the West. It is greatly to be hoped that this catalogue, along with the exhibition it represents, will play a part in fostering much-needed awareness and understanding of Sikhs and Sikhi to society at large.

This wish is optimistically expressed in the book's Preface, along with a "nutshell" overview of the origins of Sikhi and its fundamental tenets. This introductory section goes on to divide the art selected for the exhibition into three parts: a popular genre of paintings depicting reconstructed events in the life of Nanak, Sikhi's founder-Guru, images of the nine Gurus who succeeded him and shared his divine light, and manuscripts of Guru Granth, the faith's sacred scriptures. Since Guru Granth is also the living, eternal Guru of the Sikhs, it would have been considered inappropriate to install it as part of the exhibit. Instead, photographic images of its illuminated text are used on the gallery floor.

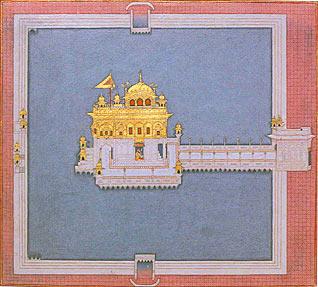

A single essay, written by the co-curators and accompanied by small illustrations showing details of more than a dozen of the show's images, precedes the catalogue. It begins with a description of the morning and evening ceremonies undertaken at Harimandir Sahib, the Golden Temple at Amritsar, revolving around the formal opening and closing of Guru Granth. The essay goes on to speak briefly of the text's compilation, and its installation as the eternal, living Guru by Guru Gobind Singh, the last human Guru, before his death in 1708. Throughout its entirety, the deepest and most abstruse thought is effortlessly translated into lyrical poetry of incomparable beauty, with intense love for and devotion to an immanent, transcendent God reflected in every line.

This section stresses two central points. The first is the fact that, although Guru Granth is considered to be one integrated whole, it is the product of Hindu and Muslim saint-poets and bards, as well as six of the ten Sikh Gurus. The second is the primacy granted to musicality, as evidenced by its unique arrangement based on thirty-one classical North Indian musical modes, or ragas.

In clear and jargon-free prose, Goswamy and Smith give a brief overview of the "three pillars" of Sikh spirituality, a framework for ethical daily living set forth by Guru Nanak. These are naam japo (the remembrance and recitation of God's Holy Name), kirat karo (honest labor), and wand chhako (sharing what one has with others). Primordial place is given to the shabd, or the sacred Word of the Guru, and great value is placed on seva, selfless service to all humanity, not just fellow Sikhs.

Although Guru Granth has no narrative content -- "prayer follows prayer, hymn succeeds hymn" -- many of its tenets are embodied in janamsakhis, literally, "eyewitness tales of a lifetime." Goswamy and Smith briefly but skillfully recount a variety of these reconstructed accounts of the life of Guru Nanak. Whether the Guru is shown in Mecca, sleeping with his feet towards the Muslim's holy Ka'aba stone, outside the hut of the poor carpenter, Lalo, enjoying the honest craftsman's wholesome food, or splashing in the river at Haridwar, debunking the Hindu pilgrims' superstitious rituals, paintings were done to reflect the spirit of these rich parables that conveyed Sikh precepts, with subtlety and humor, to all of the faith's followers.

It is commendable that Goswamy and Smith not only emphasize the fact that Sikhi is a unique religion, distinct from Hinduism and Islam, but also stress the exemplary continuity in the teachings of all ten Gurus, from Guru Nanak to Guru Gobind Singh. "No one swerved from the path that Guru Nanak had founded. The message was always the same. Nectar continued to rain; the stream never ceased to flow."

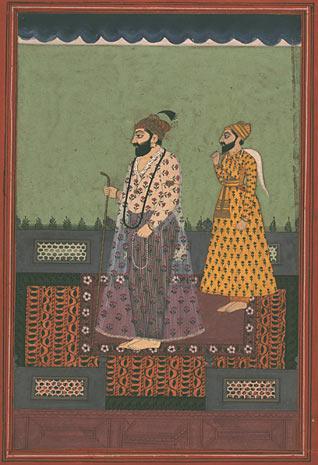

These concepts are used as an introduction to their discussion of the artistic conceptions of the various Gurus. Needless to say, Guru Nanak is most frequently depicted; however, images of three other Gurus -- Guru Hargobind, Guru Har Krishan, and Guru Gobind Singh -- have also been established with considerable clarity. Guru Nanak is almost always accompanied by his virtually inseparable companion, the Muslim minstrel, Mardana. In most portraits of Guru Hargobind, he is shown with a falcon, symbol of sovereignty, and his twin swords of miri and piri, or temporal and spiritual authority. Guru Har Krishan, who died in childhood, is, of course, always seen as a young boy. Guru Gobind Singh is often portrayed as a martial hero and man of action riding a spirited stallion, an aigrette adorning his turban and a falcon perched on one hand. The other six Gurus -- Angad, Amar Das, Ram Das, Arjan, Har Rai and Tegh Bahadur -- are also represented in Sikh portraiture, but it is not always easy to distinguish them from one another.

Goswamy and Smith then proceed to detail the evolution seen in manuscripts of Guru Granth. They characterize early ones as relatively simple and austere, often scripted by the devotees themselves. From the 17th century onward, many bore floral and geometric patterns reminiscent of Persian illumination. In the closing years of the 18th century and at the start of the 19th, richly illustrated manuscripts appear, the work of Kashmiri painters and scribes.

The authors use one of the most sumptuously illustrated manuscripts, commissioned by Sodhi Bhan Singh from a Kashmiri painter in 1839, to introduce an aspect of this exhibit that has provoked a measure of controversy and contention. This is the depiction of the Sikh Gurus among a pantheon of assorted Hindu deities, as well as symbols of that religion such as the twelve-petaled lotus and the sacred syllable, Om. They give various reasons for these types of portrayals. One of these is that Sodhi Bhan Singh came from a family outside the mainstream of Sikh orthodoxy, and was not concerned with drawing a clear delineation between Hindu and Sikh beliefs. These images might possibly be regarded as highly complimentary, pointing to the exalted status Guru Nanak had attained among Hindus, who often considered him to be a veritable incarnation of God. Furthermore, they may illustrate the fact that Sikh devotion held no hostility towards other faiths, only towards their false practitioners and mindless rituals. It is on this note that Goswamy and Smith conclude their essay, speaking of "a time when in the words of the Guru Granth Sahib, no one was a stranger."

This essay is followed by the body of the catalogue, which divides the artwork, produced for the most part during the 18th and 19th centuries, into the five sections used in the exhibition.

The first, "Searching for Answers," portrays various janamsakhis of Guru Nanak -- as a child entering school, a young man at his wedding, propagating his teachings to his followers, or speaking to holy men of various faiths during the years of his voyages. Although the historical accuracy of janamsakhis is debatable, they possess immense evocatory power in the popular imagination. Many of these images come from different generations of Pahari ("of the hills") painters in the workshop tradition of Nainsukh of Guler, which was active during the last quarter of the 18th century; others come from the Kashmir region of Northern India. This section contains what is, in my opinion, one of the most fascinating aspects of this exhibition: the existence of preparatory drawings done prior to the paintings themselves, where the similarities and differences of these two media are evident.

The second, "All is One," begins with an amazing portrait of Guru Nanak as an older man, wrapped in a robe inscribed with calligraphic verses from both the Muslim Qur'an and the Sikh "Japji" prayer. This is the section that includes the depictions of Sikh Gurus among Hindu deities, as mentioned above.

The third, "A Light Moving Across Time," includes not only additional portraits of Guru Nanak, but various depictions of his successor Gurus as well.

The fourth, "Meditations on the True Name," contains objects of devotional significance -- gold tokens embossed with Guru Nanak's image, a pair of wooden sandals evoking his travels, and water pots carried by wanderers and ascetics, among others.

The fifth, "Faith in Labor -- Warrior Chiefs," as its name would imply, shows depictions of various craftsmen at work, reflecting the high value placed by Sikhi on honest toil, as well as portraits of Sikh chieftains such as Jassa Singh Ramgarhia and Bhag Singh Ahluwalia. This section also gives a small glimpse of something otherwise largely missing from this exhibit -- an idea of the lives of Sikh women. This is not only shown in a group portrait of a princess and her female companions, but also in a stunning array of textiles known as phulkari. Literally translated as "flower work," they are said to have been originally conceived by Guru Nanak's beloved older sister, Nanaki. Woven on a base of homespun cotton called kadhi, they are made by and for women as exquisite representations of all the stages of the feminine lifecycle, and expressions of female hopes and dreams.

This book concludes with a timeline entitled "Chronology of the Sikh Gurus, the Mughal Empire, and Western History," a Glossary, and a short Selected Bibliography.

This work will enrich the experience of these who are fortunate enough to visit this exhibition in person. For others, it will serve quite acceptably as a vicarious substitute for "being there," as its illustrations are well-reproduced and of uniformly high quality. In either instance, the introductory essay, as well as the texts accompanying the images, will afford a brief, but meaningful, glimpse into early Sikh devotion. Examination of the artworks in the context of the time and place in which they were created will be extremely valuable to all readers.

Those who belong to the Sikh faith can enjoy this book as a visual representation of a seminal period in the development of their religion. While some Sikhs may indeed take offense at the works of art that portray the Sikh Gurus among a panoply of Hindu deities, others may be able to accept the explanations for these depictions given by the book's authors, and consider them to be complimentary -- that the artists so admired the Gurus that they wanted to show them in the company of revered personages from their own faith. Hopefully, all Sikhs will be able to view this book as an artistic confirmation of the richness of their spiritual heritage.

Non-Sikhs as well can appreciate what this book offers. It can be methodically paged through, cover to cover, or perused in a more casual, random way, as a "coffee-table book." Members of other faiths do not risk being intimidated or confused by unfamiliar, inadequately explained terminology, or esoteric aspects of a religion of which they may know little. Those possessing an open and receptive mind will no doubt be able to capture a feel of the timeless and universal relevancy of the teachings of Sikhi.

This book might have become a highly valuable reference work if it had included more than one essay. A piece capable of remaining on an introductory, user-friendly level, while still providing a more comprehensive treatment of Sikhi's basic tenets would have added much worth to this catalogue. An established Sikh writer with proven appeal to a wide audience would have amply filled this bill. I.J. Singh, mentioned in the book's Acknowledgement section, who gave a series of orientation sessions for the Rubin Museum's staff of guides that considerably deepened their understanding of Sikhs and Sikhi, immediately comes to my mind in this capacity. Moreover, the addition of his recent essay, "Art, Faith & History," which discusses issues of artistic freedom of expression regarding representations of religious figures, including the Sikh Gurus, would also have greatly enriched this book.

These two contributions could have been accompanied by a strictly art-related piece, aimed at clarifying the techniques and media used in the creation of the artworks, and providing an overall glimpse of the major schools of Sikh art.

The inclusion of this selection of additional writings would have left co-curators Goswamy and Smith free to display, in a main essay, the impressive arsenal of artistic knowledge they both surely possess.

Conversation about this article

1: Jassa (Canada), April 07, 2007, 6:39 AM.

i haven't checked out your whole site yet. But of what I have seen so far, I'm very, very impressed. I must applaud you for this magnificent work. Thank you.