Sports

Monty Python

by EMMA JOHN [Guardian]

"I am neither a child, nor a young man, nor an ancient; nor am I of any caste" - Guru Nanak

They call it the Monty Effect.

Since Mudhsuden Singh Panesar - nicknamed Monty by an affectionate aunt - was picked for England two winters ago, his first club, Luton Town and Indians CC, have not been able to cope with the demand. "There's a constant stream of children wanting to join," says Viren Patel, the team manager. "We could fill this place with 250 kids. But we're a small club and we don't have the resources. We're having to send them elsewhere."

Panesar's appeal, throughout and beyond cricket, has been a summer sensation. Perhaps it's because you couldn't make this person up. Some will remember the wickets he took this summer with his left-arm finger-spin - great, ripping deliveries, such as the one that bowled the excellent Younis Khan during the Headingley Test against Pakistan. Others might celebrate his being the first Sikh to play cricket for England, at a time when the search for multicultural icons has never seemed more urgent.

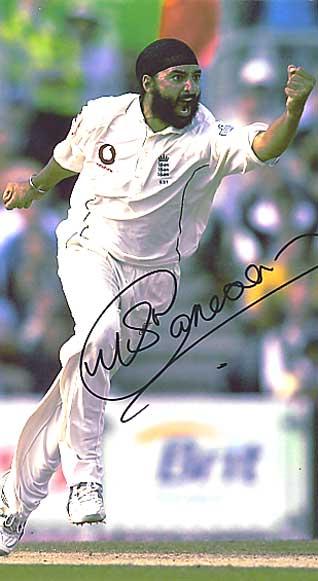

Most, however, will remember the exuberant dance that followed each of his 27 dismissals. With an elongated leap through the air, eyes on stalks, he hurled himself towards his team-mates in an ecstasy of cartoonish disbelief.

There is, too, his hapless fielding and incompetent batting that have brought ironic cheers from the crowds and so frustrated England coach Duncan Fletcher. Even after Panesar took eight wickets in the match to inspire England to victory against Pakistan at Old Trafford in July, Fletcher remained grudgingly sceptical.

"Would we need Monty on a green top?" he asked. "It's very important that we look at Monty on wickets that don't help him as much as it did [here] ... I still have slight reservations about his batting and his fielding."

We first meet in late August at the Regent Lodge Hotel in Luton, the kind of bland, dilapidated structure that has given the town such a bad rap, but it's conveniently situated near his parents' home, where he still lives and which he feels no urgency to leave. Family is important to him. Plus, his mum's an ace cook and he doesn't have to do his own laundry.

There is no sign, in the quiet man who greets me, of the bowler who glares at opponents with such intensity. Panesar is dressed casually - he has come straight from a cousin's 18th birthday party - and talks, patiently but awkwardly, about the two summer series, against Sri Lanka and Pakistan, in which, at 24, he became England's latest bowling star.

"I was very much star-struck," he says. "The team would do things to help me, like playing darts with Andrew Flintoff and Steve Harmison, getting me involved. It helped get the nerves out of my system."

Panesar has been playing county cricket for Northamptonshire for five years, but has been an England player for only eight months and retains a charming naivete. While Andrew Flintoff returns after a Test match to his million-pound house in Cheshire, Monty heads back to the family's modestly sized semi-detached. In the driveway, his sponsored BMW X5 sits alongside his dad's old blue van. A family friend, Dave Parsooth, manages his diary. The sudden demand for Panesar is tough on Parsooth, too, who combines his diary-keeping role with a full-time job at a Luton scientific supplies firm.

You suspect that, whatever the pressures, Panesar will remain largely unchanged. When the England team go out to celebrate a Test victory, he loves being with them, but he does not drink. He remains a vegetarian and no sports nutritionist will persuade him otherwise. While some British Sikhs have shed outward symbols of their faith, Monty's beard and his patka - the under-turban he wears to contain his long hair - are two of his defining features.

His athletic physique, stretched across a six-foot frame, draws less immediate attention. The brawny shoulders and biceps would be imposing if it weren't for the self-effacing nature of the man who carries them. During the days of the Ten Sikh Gurus - who lived between the 15th and 18th centuries - followers were instructed to lead an active life and wrestling became a particularly popular exercise. You sense Panesar would have done well against the early disciples.

He has become the most visible Sikh in the country. Inderjit Singh, editor of the Sikh Messenger and a well known voice for Britain's 330,000-strong Sikh community, says he is proving a fantastic role model. "He's had a huge effect on raising the morale and feelings of the Sikh community," says Singh. "There is traditionally little recognition of turbaned Sikh people. But here is a young man whose religion is his driving force. In Sikhism we are taught that if we go into anything we must try very hard. And he, more than many other cricketers, keeps working hard."

Panesar has said that religion has helped him to be disciplined. But he underplays his role as an ambassador. "Religion's a faith, cricket's a dream. They're two separate issues."

Still, his busy cricket schedule has made it difficult in the past for him to worship with his family, who attend a temple in Coventry in the Midlands, where most of the UK's Sikh population is concentrated. They're not too concerned. "It's something natural to us - we don't get into anything too deep," he says, laughing. "It's just part of me, who I am."

Halfway between Luton Town Cricket Club and Monty's parents' home is Bury Park. It's the unofficial town centre for Luton's Asian community, including its five hundred Sikhs; running through its heart is a half-a-mile long drag of Asian businesses, shops and services. Mosques, temples and even churches sit side by side; salwar-kameezes and hijabs intermingle with three-piece suits and denim. Its immigrant population began arriving in the 1950s and has since extended to the third generation. Like Panesar, most young people here speak two languages in their home.

Panesar's parents, Paramjit and Gursharan, both grew up in the Punjab, a largely Sikh state in the north-west of India. A young carpenter, Paramjit was 19 when he arrived in England in the mid-1970s to stay with family. "Mum had friends here, too - they both only came over for a visit," says Panesar. "But they met through friends and got married."

They settled in Stopsley, an area of Luton that, unlike Bury Park, is predominantly white. Paramjit began a construction business. "He's hard-working, always has been," Panesar says of his father. "He likes to keep himself busy. And he's very skilful. He works that hard because he enjoys it."

Monty was born in 1982, followed a couple of years later by a brother, Isher - who is a promising cricketer - and a sister, Charanjit. With only four years between them, Panesar says they grew up treating each other as equals: none of that big-brother stuff. "I think my Dad's there for that - he protects all of us."

All three went to Stopsley High, the local state school. The importance of education is a guiding Sikh principle; the children were taught to take their studies seriously.

Paramjit has what Panesar calls a "technical, mathematical" bent and passed the same down to his offspring. All three have shown an aptitude for science, in which British Indians are traditionally strong. "We just found it easier to study those subjects than the arts, maybe it's nature," says Panesar. Isher is now at King's College in London studying mathematical engineering; Charanjit is a biochemistry student.

Monty's three Bs at A-level, in chemistry, physics and maths, were followed by a computer science degree at Loughborough University. He has an inquisitive mind and every experience is a learning opportunity. "He definitely asks a lot of questions," says his Northamptonshire captain, David Sales. "He's always trying to find out what people think. Most of all he's keen to know the batsman's point of view: 'How would you look to play me in this situation?' "

Studies came first, but cricket same second, third and fourth. Panesar was ten when his father first took him along to Luton Indians CC. Those who played with him at the time remember a "flat-footed young lad who turned up and couldn't hold a bat". Like Ashley Giles, the player he replaced in the England team, Panesar started out bowling seamers - Pakistan's Wasim Akram was his hero - but everyone agrees that the result was pretty horrible. In fact, much though he loved games of all sorts - he threw himself into tennis, snooker, cross-country running and football - few would have given you odds on this gawky teenager becoming a professional sportsman.

Luton Indians were a family club and Monty's first coach was a friend of his father, Hitu Naik. "He was the one who was at me to try spin," recalls Panesar. Perhaps Naik spotted Panesar's unusually large handspan. Panesar looks down at his digits, which extend like spoons, and laughs. "I think the fingers may have helped."

Naik would encourage him not to worry where the ball landed but concentrate instead on turning it as much as he could. Naik taught him more than how to spin the ball. Not even Paramjit could match Naik's passion for the game, which was soon infecting the young Panesar.

"If I did good work he'd be happy," says Panesar. "That made me want to do well." Within months, Luton Indians' cricket ground, on Lancaster Avenue, had become his second home.

Panesar was not, as he concedes, the most talented guy at the club. That was his best friend, Nitin Parsooth, son of Dave. But he was the most determined. "He was never particularly agile," says one of his old team-mates, who remembers teaching a teenage Panesar an important lesson.

"There's a small bit of parkland opposite his house and I used to see him and his little brother up there all the time, practising and practising their cricket. His problem was he was flat-footed, he always used to land on his heels, so I'd take him for jogs to practise running on his toes."

One December day in 1998, Viren Patel drove past the club's ground. It had been locked up for the winter two months previously and there was heavy snow on the outfield. He saw footprints leading, in the distance, to a small silhouette throwing a ball high in the air while a larger figure bounded around beneath it, trying to judge its swirling trajectory. Patel didn't need to look twice. It was Naik and a 16-year-old Monty.

By this time, Panesar had won a sports scholarship to Bedford Modern's sixth-form college, where he was a keen badminton player and gave the county champion, also at the school, a few close games. His parents were now living closer to Dunstable, a pragmatic move. Scouted by the county's development officer David Mercer, who recognised the maturity in his bowling, Panesar was now playing for Dunstable Town and for Bedfordshire, and soon had a trial at Northamptonshire, the nearest first-class county.

Like Mercer, the coaches at Northants were amazed not only by his talent and skill, but also his determination. "There was something a bit different about him," recalls David Capel, the former England all-rounder who was then the coach of Northants' second XI.

"He had a lot of energy, and he was a real sponge for information."

It prompted an unusual decision: they offered him a contract immediately, even though he made it clear that he would not delay taking up his degree.

In 2000-01, Panesar was selected for an England under-19s tour. He had visited his grandparents in Punjab before, so the chaos and intensity of India was nothing new. But the attention he raised, as the first Sikh to play for a representative England side, was remarkable. Kirk Russell, who has known Monty for several years, was the team physiotherapist.

"None of us had experienced that sort of hype before on a youth tour," says Russell, "and everyone was talking about him."

Crowds of Indians went to watch the 18-year-old train. The travelling was not easy, either. One 14-hour round-trip to Vijayawada in midsummer heat was endured on a bus without air conditioning. "He handled it all unbelievably well," says Russell.

Panesar took a detour of his own, to Delhi, to meet the most famous Sikh ever to play the game. Bishan Bedi's left-arm finger-spin won countless glories for India and, coincidentally, he played for Northants in the 1970s. His action was the template for the young Panesar. Bedi remembers how the two discussed "the philosophy of the left-arm spin" which is, apparently, a simple one: patience.

"I liked his attitude," says Bedi. "He has great cricketing intelligence."

The following summer, Bedi brought a team of Indian youths over to England. The Panesars invited him round for dinner. "It was very kind of him to come," Panesar told me, "and it was a pleasant experience." His mother cooked lasagna especially. His father was "overwhelmed". But for all that, Bedi was treated as one of the family. "I liked what I saw," says Bedi. "They're very nice, down-to-earth people."

It was in India, five years later, that Panesar played his first Test and took his first Test wicket. His victim was the greatest Indian batsman of all time, Sachin Tendulkar. Pradeep Vijayakar's excited commentary on All India Radio captured the romantic mood.

"This is the stuff that dreams are made of. Imagine growing up in England, an ex-pat Indian boy hoping to play one day for England, and now that dream has been fulfilled, and what a message this sends out to Indian youngsters all over the world that they must have the guts to dream, and have the right to make their dreams come true, as Monty Panesar has done by dismissing the great Sachin Tendulkar at the Nagpur VCA stadium."

The rest of Panesar's India tour was not so kind. His fielding and batting were ridiculed, especially after he dropped a couple of relatively easy catches and looked out of place at the crease. He was beginning to imitate his great spin hero, the cack-handed Phil Tufnell, a little too closely. While everyone was still sniggering, he returned to Luton, and to Naik, for some serious hard work. Panesar is unfussed by the memory.

Sikhism promotes equilibrium as an ideal state - "Don't get over-excited when you do well, or really down when you don't do well," says Inderjit Singh. Instead, Panesar persevered the way his faith taught him to. International cricket was new to him, but it was not the first time he had fallen back on his good disciplines to see him through.

"The really frustrating time was the two years when I didn't play first-team cricket for Northamptonshire," he told me. The nadir came at the start of a second XI match when Panesar discovered he was one of 12 players on the pitch. The coach, the former England spinner Nick Cook, came on to tell him he wouldn't be taking part. "I just had to persevere and stay patient. David Capel [now Northants head coach] said keep enjoying it, and keep doing your stuff well, because at any time you could get your chance. I always had that in the back of my mind."

The second time I meet Panesar, he says very little. We've met, along with Parsooth, for a lemonade and a quick chat. Parsooth fills me in on Panesar's schedule, which is becoming ever more demanding; he has also changed agents and is now with Paragon Sports Management. Panesar, meanwhile, is texting insistently. He's a veteran, his right thumb hammering the keypad like a piston.

His shyness and his impatience to be with his friends keep him zoned in on the mobile phone. It's not a front, but it is a contradiction. The young man who expresses himself on the cricket field with such enthusiasm, such abandon, turns out when you meet him to be so contained that all emotions are as one.

Sometimes, I get the sense that it's distrust; that he's watching me, as he would an opposition batsman. I can only listen, enviously, to the descriptions of those such as Capel and Sales, who know him as "bubbly" and "a real chatterbox". Or the memories of Kirk Russell, who has seen an excitable Panesar perform hip hop to his team-mates: "He thinks he's a bit of a rapper."

Panesar loves music - R'n'B is a particular favourite - but clubbing and dancing have never been his scene. Good times mean something simpler. I once asked for his favourite childhood memory. He thought hard, then answered: "Probably when I got my GCSE results. We'd all done well, we were really happy, and we spent the day just hanging around town together."

Those friends, who have gone on to be engineers, accountants, traders, remain a close-knit group, still go to the cinema together, still play five-a-side football on Luton's Astroturf pitches whenever they can get a game.

It's October, and Monty is back from an extended break at the end of the cricket season. Only a month has passed since we last met, but life has taken on a tangibly different flavour. He has been named in the Ashes squad, which, after this summer's achievements, is both the reward and the challenge he craved. His career so far has become mere preparation for the winter to come.

The commercial side, too, has acquired a new urgency since we last met. Operation Monty is go. There's merchandise, an appearance on A Question of Sport, and a website (monty-panesar.com, soon to go live). There is the obligatory book deal: Monty has signed a reported £300,000 contract with Hodder & Stoughton that will, I have been told, preclude him from talking about anything personal - his family, his upbringing, his faith - until the book is published. I have never heard of such a gagging order before. For someone as reticent as Panesar, it's like putting a muzzle on a poodle.

We're back at Luton Cricket Club. Panesar pulls up in his hulking silver 4x4. Parsooth's here, too, straight from his day job. He wants to know if Monty should do an interview for ESPN in America. Well, is Monty keen for American exposure? No one seems sure. But their expectations are growing and there's a feeling that he should be doing better out of sponsorship opportunities.

I like Parsooth; he's caring and humorous. Still, when he takes a call I could swear he's about to shout out the command from the film Jerry Maguire: "Show me the money!"

Monty hacks and coughs, but stands patiently for the photographs, determined, as ever, to give of his best.

We retreat to Parsooth's house, a large semi-detached behind one of the sightscreens at the northern end of the pitch. The family dog is sent upstairs - Panesar doesn't like dogs - and we sit in the dining room, which serves as Parsooth's office, and drink the chai his wife brings us. There are, still, glimpses of Panesar's naivete. I show them a copy of the latest GQ Sport, which features him on the front cover, and joke that he's sharing the magazine with Jude Law. "Who's she?" Monty asks.

Panesar, it transpires, is happy to answer personal questions after all. So I jump straight in. Sikh marriages are usually arranged. Will his parents be doing him the same service? "No, not really, they're pretty open-minded parents. They let me do my relationships." Like all other aspects of his life, he plans to pursue them discreetly, and although he has a girlfriend, a university student, he doesn't like to talk about her.

We talk, instead, about the Ashes. At the first mention of the tour, he perks up. His animation carries an echo of the player I recognize from the field.

"It'll be so exciting, bowling to all of the Australian players," he says. "They have done so much for the history of the game."

Is he aware of the less charitable comments that the Australians have been making about him? Glenn McGrath has said that he's "soft" for talking to the England team's sports psychologist, Steve Bull.

"I think I heard it on the TV," Monty says equably. "It's something you just accept."

Another tenet of Sikhism, and one of Panesar's favourites: create no difference with anybody. As Bishan Bedi says, Panesar chooses another path. "He's a well brought up Punjabi and he's hanging on to his identity as a Sikh. I think he quite likes to be different."

Kirk Russell agrees. "It's funny," he says, "he is different, and not just because he's the only Sikh in the team. He's always got a smile on his face - even on a bad day he'll smile. I've never seen him lose his rag. That's why he'll do well in Australia."

I ask Panesar how he would describe himself. He says he's never really thought about it and tries to evade the question. "I probably just try my best at everything," he says, eventually. "And if anyone needs any help I'll try to give them whatever help I can."

It's surely no coincidence that he's just described two of the guiding principles of Sikhism.

But he hasn't finished. "And enjoy each moment as it comes."

[Courtesy: Guardian Unlimited]

Conversation about this article

1: Satnam Singh (Vancouver, Canada), May 23, 2007, 3:21 PM.

A very well written and inspiring article!