Daily Fix

The Man Who Knew Everything:

Part II

T. SHER SINGH

It was in the 1960’s, a little more than a dozen years after independence, that things began to slide in India.

Nothing seemed to be moving forward in the country. Hence, a growing nostalgia for the good ol’ days of the British Raj. Gone was the initial euphoria of being free, long since taken over by the stink of those cashing in on wild and exaggerated claims of having ’fought’ in the struggle.

The miniscule middle-class, well-fed enough to spare the time to think, would look enviously at their Pakistani neighbours. In one breath, they cursed the betrayal of the partition, in the next they yearned for a dictator of their own … one who could get the trains back on time.

By this time, Nehru -- the only leader India had had since its creation -- had proved himself to be no more than a pretty face who could talk up a storm in his Cambridge intonations, but do little to pull out the country from its medievalism. To make matters worse, he had taken India to the brink by starting and then badly losing a costly war to the Chinese. Then, in shame, he withered away … and, conveniently for the country, died. In 1964.

It is with this backdrop that the wacko underbelly of Hinduism began to rear its head around the country, egged on by warped interpretations of its obscure texts, and turning to extreme positions in its slide towards militant fundamentalism.

Pakistan increasingly became the bugaboo, the explanation for all of India’s ills. Hence, the openly stated goal to destroy it and bring back the ’errant’ Muslims to the fold … which, in Hindutva parlance, meant ‘putting them in their place‘.

A country-wide campaign was launched to make Hindi the sole national language ... by removing all traces of English from public or private life. It was a two-pronged action plan.

First, the process of sanskritizing the Hindi language because, it was argued, it had been contaminated in recent centuries by Urdu. The language spoken by the masses was no longer acceptable. It had to be purified; only the fossilized language-code of the pre-historic Vedas would do.

Secondly, mobs began to scour neighbourhoods, painting over English signs to make the point that only the Hindi script was to be used. If your car license plate was in English letters and numerals, you would be stopped mid-street by a handful of goondas with brushes and cans of paint, and the plates would be given an instant paint-job. If they slobbed some on the car itself, well, that was your problem. If you protested, you were pulled out of your car and thrashed.

The next, natural step was to proclaim the ‘Gau Raksha Andolan” -- the Movement to Defend the Cow. All government agencies were to recognize the supremacy of the Cow and no expense was to be spared to help ‘protect’ and ‘nurture‘ the Nation‘s Mother.

There were corollaries to the 'holy cow' sentiment. If a cow strayed onto a road or highway, the traffic was to patiently wait for it to move, or go around it. The cow, being holy and the 'Mother of the Hindus' couldn't be messed around with. Next: surely, the consumption of beef had to be banned from the holy precincts of Hindustan!

Then, the movement to purify each populace. Henceforth, we were told, Bengal was for Bengalis, Gujarat for Gujaratis, Maharastra for Marathis, etc., etc. Those who didn’t ’belong’ were to go back to their ‘own’ states. The fact that families by the millions had been living in different parts of the country as local-borns was to be of no consequence. Flash mobs would -- and did - decide on the spot if you met the criteria.

And so on and so forth progressed the insanity that began to infect the country. Anarchy and mayhem was to be expected any where, any time. You simply had to learn to lie low until things blew over, if it was your area that was affected.

Then there was the phenomena that every cause required public protests and demonstrations in which everyone -- yes, E-V-E-R-Y-O-N-E -- had to participate.

The ’bandh’ -- a new version of the strike requiring all public activity to be shut down, and the streets be deserted -- was re-invented.

So was the ‘dharna’, whereby a crowd of hooligans would storm a government office (or that of a university or any other targeted institution) and occupy the premises, day in and day out, until the demands were met, no matter how outrageous they were. The occupants of the office were held hostage. No one could leave, no one could enter. No food or water or medical supplies. No bathroom breaks.

How Gandhian!

I recall our university classes being cancelled for weeks, sometimes even months. Exams would get postponed indefinitely. Unpopular Vice-Chancellors and professors got beaten or humiliated, publicly.

All was not lost, though. You could buy protection from the dominant caste group in your area. Once you became their ’client’, you were guaranteed safety.

And where was the media, the watchdog of democracy, through all of this?

With the British long gone, with little law and order to replace theirs, journalistic and professional standards had become even more malleable. As a media outlet, you were either aligned to one group or the other, or you kowtowed to the flavour of the day.

There was no civic pride, no identification with the nation as a whole, no understanding of or commitment to the greater or common good.

It is into this melee that Khushwant Singh stepped in.

He was wooed and cajoled and pampered for years until he finally relented and agreed to take over as Editor of “The Illustrated Weekly of India“, known by the few who read it then as the ‘Weekly‘.

It was at this time, essentially, a weekly adjunct to the news daily, The Times of India. It had been started in its original incarnation in 1880 as a loose imitation of The Illustrated London News, which had been launched a few decades earlier. But the Indian version never managed to reach its English counterpart’s standards or circulation levels, even though the British target population was but a fraction of the subcontinent’s.

It was probably because the London journal was heavy on news and crime coverage, with a clear emphasis on the illustrated aspect of it, to which it did considerable justice.

The Weekly in India, however, became more of a society rag, covering the antics and shenanigans of expats who turned up on every transcontinental boat in droves, looking for employment, adventure and advancement. Since being merely British-born, pigment-challenged, and little more, was the primary qualification required for the top jobs in the land, most of the coverage in the Weekly was of, relatively, a dull nature. Free-range gossip, endless notices of arrivals, departures, betrothals, dances and comings-out, were the journal’s mainstay.

With the departure of the Brits in 1947, the Weekly’s raison d’etre seemed to evaporate into thin air. It stumbled along with its British editor for a few more years until both he and the journal’s new Indian owners realized the futility of having him around.

The Weekly’s first Indian editor came along. His qualifications? An economist with a special interest in Hindu mythology, Avadhanam Sita Raman had been hand-picked -- the rumour goes -- by another expert in Hindu mythology: Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, the then Vice-President of India.

Needless to say, the Weekly limped along for a few more years until its owners were left with two options: to infuse a shot of adrenalin or pull the plug.

Enter Khushwant Singh.

By the time he took over the Weekly, it’s circulation had plummeted to around 60,000 per week. That is, on an average, a mere one copy was read between the entire population of a dozen towns and villages in the country.

I was in my late teens when I began to notice a ‘new’ magazine on the news-stands in Patna. “New” because even though I had noticed the masthead before, and even picked up the magazine a few times, it had failed to interest me. For a magazine that labelled itself ‘Illustrated“, it was lack-lustre; its choice of articles was obtuse; its connection with all that was going on in the country or the world, tenuous, to put it kindly.

So, what had caught my eye now was indeed ‘new’.

It grabbed my attention, I remember, because of its vibrancy --- in its colours, its new cover design, its daring imagery. And its let’s-push-the-envelope Table of Contents. The book-seller -- who I knew well because of the hours I spent hanging around his store every week -- yelled out from behind the counter: “It has a new editor, that’s why! Khushwant Singh!”

In short shrift and quick succession, each weekly issue appeared to be a Special Issue. One focused on the Muslims of India. Then the Buddhists. Another on the Jains. India’s Christians. India’s Jews. [India had Jews? That was an eye-opener!] The Hindus, of course. And, lo and behold, one whole issue on the Sikhs.

It was as if someone had suddenly discovered that there was a multiplicity of communities in India, each with a rich lode of its own heroes and giants, its own literature and poetry, its own heritage and history, its own dreams and aspirations ....

Each weekly edition was a jaw-dropper. We were discovering a new India. And began to notice things around us which had, oddly, escaped our attention until now, even though we were surrounded by them.

People. Places. Customs. Practices. Beliefs. Attitudes. Behaviour. Mannerisms. Each other’s music and foods and festivals.

All of a sudden, the religious processions we saw clog our streets every now and then, began to make sense. We nodded ours heads knowingly in our respective corners, seeing the similarities and began to enjoy each other’s eccentricities.

It didn’t take long before the Weekly itself was making news. It had achieved a miraculous and unprecedented turn-around. From a measly 60,000 circulation, it was now surpassing the 400,000 mark. On specific issues, it was selling a hundred- or even two hundred thousand more!

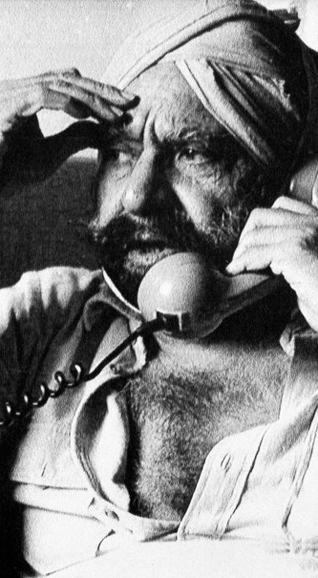

Its editor -- the Sardar in the Light-Bulb, as he was now lovingly referred to, because of his signature logo -- was being hailed as a marketing wiz.

And people were beginning to rave about his writng too. It was daring, uncompromising, irreverent, fearless, humorous …

And something else.

Bawdy.

He made fun of the country’s hang-ups, and challenged it to be honest with itself. To shake off its Victorian pretensions and face its dreams and its nightmares honestly.

And the bottom line?

The more he pushed them, the more he dragged them kicking and screaming into the twentieth century -- about time, he said, we’re way into the second-half! -- the more they loved him.

His staff was dumb-founded. They refused to increase the numbers of copies they printed each week as fast as he wanted to. As a result, there was always a shortage.

Back where I lived, our book-seller -- he was the only source for the Weekly in the city, his copies being shipped in by express train and picked up and brought to his store by the early afternoon each Tuesday! - insisted that we reserve our copies by paying him in advance. Otherwise, sorry …

And there was more.

He had a standing offer: if we returned our copies to him within four days, he would buy them back at cover price. Thus, he could re-sell them to those on the waiting list at a premium. “Black” was the term used for such a practice.

Imagine! A weekly magazine -- not Playboy, not Hustler -- but The Illustrated Weekly of India was selling on the black market!

But very few availed of his offer, because they were quickly becoming collector’s items.

Khushwant Singh’s own column became addictive. And the columnists he brought in were ‘different‘. They knew how to write English -- proper English, that is, not the desi pidgin version -- and they thought outside the box.

There was one -- unfortunately, I don’t remember his name any more -- who I think of even now, every time I sit down to write a political column. He always looked at things from a novel perspective, questioning the very basics, and never satisfied by easy answers. I remember he got his break on the Weekly, and then went on to become one of the leading political commentators in the country.

The Sikhs? They loved it all for a simple reason: for the first time, our stories were being told in a national journal. Accurately. Respectfully. Thoroughly. There was a piece on the martyrdom of Guru Tegh Bahadar, for example. Another on Hari Singh Nalwa. A Special issue even on the “Ramgharias” who, hailing themselves as an artisan class within the Sikh community, laid claim to a whole slew of leading architects, engineers, builders, artists, and craftsmen who had left an indelible mark on the nation.

It wasn’t that the Sikhs were suddenly getting special treatment from Khushwant Singh because he was a Sikh. It was that we were getting a fair share of the coverage for the first time.

It was widely recognized that the new editor saw the country with the eye of a Ranjit Singh … all its constituents were looked upon as full-fledged equals. He seemed to be able to find a new, hitherto undiscovered community week after week and put it in the national spot-light.

We are a community of communities, he said, and celebrated the land and its people like they hadn‘t been since Ranjit Singh.

No wonder the people of India fell in love with him. I can’t think of another person in India even today who is as well known and hailed universally as this man. And all of it goes back to the days in the 1960s and 70s when he breathed life into a comatose journal and introduced the country to the joy of reading.

When my family and I immigrated to Canada in 1971, I didn’t have the heart to leave my collection of Weeklys behind. They were invaluable as a reference on India. I packed them up in a box and shipped them off, along with the rest of my choice books. I hung onto them for decades, until a flood in the basement claimed them a few years ago.

There’s a footnote to Khushwant Singh’s journey with The Weekly. He resigned as Editor in 1978 or so because of a difference of opinion with the owners: he had refused to be dictated by them on editorial policy.

The Weekly spluttered along thereafter under two other editors. Until it finally died in 1993, starved of the genius it had become accustomed to as its diet.

The people of India -- remember, it was a time when a wacko and virulent form of Hindu fundamentalism had begun to infect the land -- saw in Khushwant Singh an antidote to the madness and readily lapped up every word he wrote.

But, like Manmohan Singh, he too found himself outnumbered in a sea of hyenas.

To Be Continued …

[To access Part I of this article, please CLICK on the "DAILY FIX" box on the top right-hand corner of the sikhchic.com homepage, which will take you to the index. Scroll down ...]

March 25, 2014