Talking Stick

Passages:

The Talking Stick Colloquium #58

Convenor: RAVINDER SINGH

I have borrowed the title for this week’s colloquium from Gail Sheehy’s Passages, which made quite a splash in the late seventies - some of it for the wrong reasons. I stumbled across a write-up on Sheehy’s sequel, Passages in Caregiving and that caught my attention.

My interest in presenting this to you is to provoke some thinking around notions of human development and the life cycles (or stages) that we appear to go through, the “crisis” or fracture that we experience and the therapeutic models of healing offered by Gurmat and the Freudian traditions of the West.

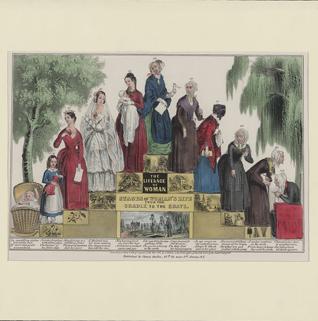

The notion of passages or stages of life is, of course not new or confined to any one region of the world.

Shakespeare’s As You Like It speaks of the world as a stage and the seven ages of man that starts with childishness and ends with a second childishness - sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans every thing.

The Hindus divide life into four stages with clearly marked duties and activities for each.

In the West, Freud’s rigid determinism that personality takes its final shape during infancy was challenged, first by his disciple Jung, and more recently by psychologists like Erik Erikson. In his now classic study of Gandhi (Gandhi’s Truth), Erikson showed that that later experience and what he calls an “identity crisis,” (in this case, the Ahmedabad steel workers strike in 1918) were important shapers of personality.

Reading about Sheehy’s latest book got me wondering about the passages from gurbani that speak to the stages of human life. Several passages in gurbani speak to stages of human life (one from Kabīr comes to mind, and there is of course, the very familiar salok of Guru Tegh Bahadar), but I picked one from Guru Nanak for consideration this week.

Pahilai piār lagā thaṇ ḏuḏẖ.

First, the comforting love of mothers’ breasts

Ḏūjai māe bāp kī suḏẖ

Second, awareness of parents,

Ŧījai bẖayā bẖābẖī beb

Third, of brothers and sisters-in-law,

Cẖauthai piār upannī kẖed

Fourth, the desire for play,

Punjvai kẖāṇ pīaṇ kī ḏẖāṯ.

Fifth, the race for food and drink,

Cẖẖivai kām na pucẖẖai jāṯ.

Sixth, lust knows no boundaries,

Saṯvai sanj kīā gẖar vās.

Seventh, settling down with spouse,

Aṯẖvai kroḏẖ hoā ṯan nās

Eight, anger wreaks havoc

Nāvai ḏẖaule ubẖe sāh.

Ninth, the greying begins

Ḏasvai ḏaḏẖā hoā suāh

Tenth, the return to dust,

Gae sigīṯ pukārī ḏẖāh

Companions crying aloud

Udiā hans ḏasāe rāh

The soul-swan has flown not knowing the Way.

* * * * *

Ḏas bālṯaṇ bīs ravaṇ ṯīsā kā sunḏar kahāvai

At ten, was childhood, at twenty, a blooming youth and at thirty, fetching good looks.

Cẖālīsī pur hoe pacẖāsī pag kẖisai saṯẖī ke bodẖepā āvai

Full of life at forty, the stride slows at fifty. At sixty, old age catches up.

Saṯar kā maṯihīṇ asīhāʼn kā viuhār na pāvai.

At seventy, a diminishing intellect, and at eighty, the world becomes a chore.

Navai kā sihjāsṇī mūl na jāṇai ap bal.

Bed ridden at ninety, stupefied by the embrace of feebleness.

[GGS:137-138]

LETS CONSIDER:

There is striking similarity in Guru Nanak’s delineation of human life and Erikson’s so-called epigenetic principle, the notion of a predetermined unfolding of our personalities: for instance, the first line speaks about the comforting love of a mother’s breast, an infant experience that Erikson defines as oral-sensory and one that is designed to inculcate the habit of trust.

But it is the differences in the paradigms of healing that are of greater interest because it seems to me that diaspora Sikhs confront them in their daily lives in the form of cultural contradictions, issues of identity and assimilation.

The gurmat paradigm of healing is explicit in the following preamble by Guru Nanak to verses being discussed here:

Gur ḏāṯā gur hivai gẖar gur ḏīpak ṯih loe

Guru the Giver, Guru the Abode of Peace, Guru the Light of all Worlds

Amar paḏārath nānkā man mānīai sukẖ hoe.

Fix your mind on the Guru – the ultimate wealth

[A Caveat: here, the word 'Guru' is used for Waheguru, and not for Guru Nanak himself.]

How does the gurmat model fit into the framework of the West that rests on the works of people like Freud, Jung, Adler, and Piaget?

Maybe the psychologists in our midst can help develop this dialogue.

August 22, 2011

Conversation about this article

1: Prakash Singh Bagga (India), August 22, 2011, 2:48 PM.

Ravinder Singh ji: I would like to bring to your notice that in the bani of the Vaars in Guru Granth Sahib, it is the saloks along with relevant pauris that gives the complete message. Here you have given only one salok and one other. There are in fact three saloks and one pauri, which give the complete message.

2: Ravinder Singh (Westerville, Ohio, U.S.A.), August 22, 2011, 5:31 PM.

Prakash Singh ji: Thanks. I realize (now) that I failed to state that I was being deliberately selective - including the pauri would have made the piece longer than I wanted it to be. My thought was simply to pick a couple of saloks to get the discussion rolling, assuming that most readers are familiar with the source. In any case, thanks for pointing out the lapse.

3: Ravinder Singh (Westerville, Ohio, U.S.A.), August 24, 2011, 4:11 PM.

My interest in this topic stems in part from the contradictions I face from being shaped by two different cultures with diametrically opposed views of the self. The very emphatic notion of individualism (with all its expressions) in the West is quite muted in the East, where the larger unit, be it family or social structure is more important. One manifestation of this difference that I see is that we Sikhs don't quite know how to be assertive - we are either too aggressive or defensive. Despite our assimilation into Western societies, some of us still view each other very much through filter, such as caste (jutt, khutri, etc). More later.

4: Ravinder Singh (Westerville, Ohio, U.S.A.), August 25, 2011, 1:53 PM.

Evidently, this is an issue that I alone seem to be pre-occupied with! Or maybe I am having trouble framing it. More later.

5: Prakash Singh Bagga (India), August 25, 2011, 2:14 PM.

We should realize that the English transliteration from Gurmukhi words in gurbani is incorrect in several ways, which is a fundamental cause of confusion in their interpretation. For this reason it would always be better to give the Gurmukhi version too. [EDITOR: That is why we give the citation - the Gurmukhi version can easily be accessed online.]

6: Yuktanand Singh (MI, U.S.A.), August 27, 2011, 1:35 PM.

There are various ways to approach it. We can learn from each approach and thus I did not want to disrupt your train of thought. It is tempting, and useful, to compare gurbani with science, philosophy, psychology, the oral/anal fixation, etc. as a didactic exercise, but it is difficult to draw these parallels beyond a very short distance. We are compelled to notice that the stress here is on regaining something that we have lost, during all (or any) of our developmental stages. It appears that analyzing each developmental milestone was not the intent of these verses, but to impress the urgency, to seize the opportunity before senility has taken over. I am curious to learn from other insights.

7: Yuktanand Singh (MI, U.S.A.), August 27, 2011, 1:45 PM.

We are born as spiritually-aware beings. But we are born without an intellectual grasp. This serves us well, but only as infants. The cognitive development that is required for our survival in the world breaks us away from the spiritual state, our simple awareness of the self. Then, the hormones and the hungers take over and replace it entirely. Ideally, we would attempt to regain it as soon as we are aware of our loss. The so-called misfortunes repeatedly beckon us to look inwards, away from the world. But we live in denial. To fill this emptiness, we analyze everything under the sun except analyzing who is behind our own eyes, our own mind, and in every heart. An intellectually honest person dies bewildered because not all experiences have a rational explanation. Others retain their sanity through a 'rational' dismissal citing the scholars who have done so successfully in the past. Thus, we die a manmukh living as a social animal, rather than living as a gurmukh or a spiritually fruitful soul.

8: Ravinder Singh (Westerville, Ohio, U.S.A.), August 28, 2011, 9:31 AM.

In concluding this week's discussion, I would have to agree with Yuktanand ji's comment that drawing parallels between gurbani and science and other disciplines can only take us so far. Actually, I would go further and say that drawing a parallel, or making comparison, is not even correct. For a Sikh, gurbani is supreme and other modes of inquiry and thought are just subordinate tools used - to borrow Yuktanand ji's word - for a didactic exercise such as this one. Sometimes, it can deepen our understanding of gurbani.

9: Ravinder Singh (Westerville, Ohio, U.S.A.), August 28, 2011, 9:44 AM.

Perhaps the passage I picked from gurbani was not the most appropriate to draw out the discussion around the notion of "ego" in a Freudian (western psychoanalytical sense) and the sense of a separate self, "haumai" in gurmat parlance. It would have made an interesting inquiry, I thought, because the two terms are a great example of how, to quote Prakash Singh Bagga ji, the translation/ transliteration of English terms to gurbani terms can be the source of confusion. In this case, our trouble begins when we use ego and haumai interchangeably.

10: Mohan Singh (Toronto, Ontario, Canada), August 28, 2011, 10:15 AM.

Comparing our Guru with some ordinary philosopher reveals our lack of confidence in our own gurbani. No one is greater then the Guru. Our gurbani is the divine word, spoken by our Gurus.

11: Prakash Singh Bagga (India), August 28, 2011, 11:57 AM.

If we make reference to Guru as one in human form - in the context of the verses being canvassed, for example, then we have made an error. Gurbani guides us on this: "sach poore gur updesiyaa Nanak sunaavae". [EDITOR: A gentle reminder - if readers give us quotes from gurbani, without a proper English translation and citation, it is then of little or no benefit to most of our readers."