Partition

Train to Pakistan

A Book Review by MANJYOT KAUR

TRAIN TO PAKISTAN, by Khushwant Singh. Photographs by Margaret Bourke-White. Roli Books Pvt Ltd, New Delhi, 2007. Illustrated Edition. ISBN-13: 978-81-7436-444-9. xxv + 263 pages. Price: Rs. 495.

As a writer of towering stature (in addition to being an accomplished journalist, columnist and historian), Khushwant Singh needs no introduction. Train to Pakistan, which marked fifty years of its existence in 2006, remains his all-time classic work. A bestseller when it was first published, it is now widely accepted as being one of the most important examples of modern Indian fiction.

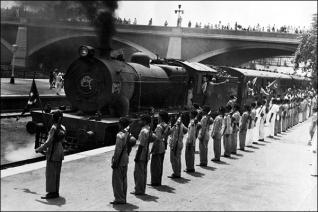

Margaret Bourke-White is considered one of the most influential photographers and photojournalists of the twentieth century. A native New Yorker, she was associated for many years with Life magazine, a publication with heavy emphasis on the power of visual imagery.

In March 1946, she was sent by Life to cover the Indian subcontinent, as "an eyewitness to the fall of the British Empire". There, she produced photographs of extraordinarily powerful impact, some of which are widely considered to be among the most poignant ever taken. Dozens of these utterly heart-rending pictures, many never before seen by the public, are included in this latest incarnation of Train to Pakistan: an illustrated edition released earlier this year.

Its front cover bears an attached sticker stating: "Disturbing images inside" - this is indeed the case.

As Pramod Kapoor writes in this book's excellent introductory section, this special edition, published to commemorate sixty years of Indian independence, is "an exercise in perpetuating the memory of those who perished and a lesson for future generations to prevent a recurrence of this tragic chapter in our history".

In his own preliminary remarks, Khushwant Singh opines that, for millions of people, history has been divided into two distinct eras: "BP (Before Partition) and PP (Post-Partition)". He characterizes Partition's aftermath as "beastlier than anything beasts could have done to each other", describes the "deep sense of remorse" that "set in on both sides when ill-temper and hatred abated", recounts several touching stories of relatives and friends whose lives were indelibly altered by these events, and proffers his opinion that "the only way to prevent their recurrence is to promote closer integration of people of different races, religions and castes living in the sub-continent".

The first line of Train to Pakistan is typical of the author's matter-of-fact sense of understatement and irony that thoroughly pervades the entire book:

"The summer of 1947 was not like other Indian summers".

The reader is then immediately taken on a tour of the novel's setting, the border village of Mano Majra. At the narrative's start, we are told it is one of the area's few remaining "oases of peace". In this hamlet live about seventy families, only one of them being Hindu; the rest are divided equally between Sikh and Muslim.

Mano Majra has always been known for its train station and its proximity to a major railway bridge. Although not many trains actually stop in the town, Singh tells us, using a plethora of charming little details, how the entire routine of daily village life is closely regulated by their comings and goings.

The plot's action swings swiftly into gear, during a chilling scene in which Ram Lal, the head of Mano Majra's only Hindu family, is brutally murdered in his home by dacoits. This episode results in our introduction to two of the book's main personages.

One of them is Hukum Chand, the magistrate and district deputy commissioner, often simply referred to as "the Government". In a work replete with in-depth characterizations, his is among the most finely delineated. This is often adroitly accomplished through his own thoughts. As communal bloodshed begins to occur on both sides - killings of Sikhs and Hindus in newly-created Pakistan and retaliation via an attack on a Muslim refugee train - Hukum Chand's mindset evolves accordingly.

"Life was too short for people to have consciences. You took it as it came, shorn of silly conventions and values which deserved only lip worship. (...) The only absolute truth was death. The rest was to be taken with a pinch of salt. What did it really matter in the end?"

The other is Juggut Singh, the infamous village gangster, or "Budmash Number Ten". As the author pithily informs us, "His equation with authority was simple: he was on the other side". Despite Juggut's well-deserved reputation for lawlessness, it is clearly evident to us that he bears no guilt for the killing of Ram Lal, as that night, we see him off in a field on the outskirts of town, lustily enjoying the seductive charms of his clandestine lover, Nooran, the daughter of the village mullah, Imam Baksh.

The next day, a train provides the vehicle for us to meet two of the other principal characters. One of the few passengers disembarking at Mano Majra is Iqbal, a Communist Party social worker educated in England. The deliberate ambiguity of his first name, which could be Sikh, Hindu or Muslim (we are not told his surname), is emblematic of his unexpected and mysterious arrival.

He is told to seek lodging at the village's gurdwara, presided upon by the granthi, Meet Singh. The author gives his sense of irony ample expression in Iqbal's pompous thoughts and pronouncements. Although he outwardly promotes the uplift of the masses as a whole, he takes quite a dim personal view of them as individuals. As he confides to the granthi during one of their first conversations, "Morality, Meet Singh ji, is a matter of money. Poor people cannot afford to have morals. So they have religion".

In reality, however, the ordinary townspeople, while leading simple and often downtrodden lives, are portrayed as pragmatic and astute. As one of them remarks during a conversation with Iqbal, who is unsuccessfully exhorting them to participate in his esoteric conception of the class struggle, "Freedom must be a good thing. But what will we get out of it? Freedom is for the educated people who fought for it. We were slaves of the English, now we will be slaves of the educated Indians, or the Pakistanis. (...) We were better off under the British. At least there was security".

The absurd, evidence-less arrests of Juggut Singh and Iqbal for the murder of Ram Lal are quickly followed by even more ominous occurences: the arrival of two "ghost trains" from Pakistan, full to overflowing with murdered Sikhs and Hindus, all of whom have been gruesomely hacked to pieces or bludgeoned to death.

After the thousands of bodies are cremated in huge piles or bulldozed into mass graves, escalating acts of horrendous manmade mayhem are joined by the turbulent forces of Mother Nature herself. During the monsoons, as the turbid floodwaters of the Sutlej River that borders the town begin to rise unchecked, the gory remains of Muslims killed in retaliation float by, joined by the carcasses of their still-yoked cattle and horses. Flocks of vultures hover ubiquitously overhead, ready to devour the dead.

Whether he is describing the hellish scenes inside the "ghost trains", the smell of burning human flesh, or a stream choked with bloated corpses, the simple, everyday manner in which Khushwant Singh speaks of the unspeakable, only serves to make his depictions of the mind-boggling carnage perpetrated by both sides even more hauntingly powerful.

Here is one example, as viewed by a group of Sikh villagers gathered on the riverbank after the rains had ended: "An old peasant with a gray beard lay flat on the water. A child's head butted into the old man's armpit. There was a hole in its back. There were many others coming down the river like logs hewn on the mountains. (...) Some were without limbs, some had their bellies torn open, many women's breasts were slashed. They floated in the sunlit river, bobbing up and down".

Before these happenings, when Mano Majra was as yet untouched by the results of Partition, the town's Muslims had been reluctant to join their co-religionists making their way westward. As Imam Baksh remarked to his Sikh counterpart, Meet Singh, "What have we to do with Pakistan? We were born here. So were our ancestors. We have lived amongst you as brothers".

In touching displays of true interfaith solidarity, Mano Majra's Sikhs had always pledged to defend their fellow villagers, even at the cost of their own lives.

However, groups of now-homeless Sikh refugees have started pouring eastward across the border into India, bearing horrific reports of massacres and desecrations. As has been the case throughout the entire book, the author's sense of understatement and irony (here, with added doses of sarcasm) immensely enhance his already potent prose.

For example, there is the following recounting of the fate of young Sundari, who "made her tryst with destiny on the road to Gujranwala". Alone with her husband for the first time in their four-day-old marriage, her arms still covered with red lacquer bangles and her palms bright with henna, she is happily day-dreaming on her way to her new home when the bus on which they are riding is attacked by Muslims. Her husband is stripped naked and dismembered before her eyes; she is gang-raped. "The mob made love to her. She did not have to take off any one of her bangles. They were all smashed as she lay in the road, being taken by one man and another and another. That should have brought her a lot of good luck!"

Plunged into the abyss of religious hatred, Mano Majra becomes a chaotic battlefield of conflicting loyalties. Hukum Chand realizes that the local situation is now an untenable one, and that his duties as a magistrate lie in getting the village's Muslims to leave as quickly and painlessly as possible.

While their evacuation to a nearby refugee camp is supposed to be only temporary, it soon becomes clear that they will never return to their homes (which are quickly looted), but will shortly be taken away by train to Pakistan. When a plot is fomented to sabotage the train as it crosses Mano Majra's railway bridge, events spiral totally out of control.

Imagining himself at the center of the crisis, and feverishly devising ways by which he might use the situation to become a glorious hero, Iqbal wrestles with the concepts of sacrifice and self-preservation, the difference between intrinsic and perceived goodness, and the eternal struggle between right and wrong. But, entangled in his own web of abstract ideas, paralysis by analysis is the only result he achieves: "Wrong triumphs over right as much as right over wrong. What happens ultimately, you do not know. In such circumstances, what can you do but cultivate an inner indifference to all values? Nothing matters. Nothing whatever..."

It will all come down to one man - Juggut Singh - in an immensely thrilling climax that is guaranteed to have you enthralled until the book's very last word.

Train to Pakistan is a tremendously absorbing novel that tells a highly believable story from multiple viewpoints. Among its motley assortment of brilliantly-crafted characters, there are no "good guys", no "bad guys". No blame is ever placed on a particular group; all are held responsible. As Khushwant Singh says in one of the book's first paragraphs, "The fact is, both sides killed. Both shot and stabbed and speared and clubbed. Both tortured. Both raped".

Indeed, one of the major hallmarks of this tautly-woven narrative is its impressive sense of authenticity. (There is one very small exception: a few formal-sounding euphemisms - "You seducer of his mother!", for example - have crept into the dialogue's exclamations. It must be remembered, however, that this book was written in 1956.)

Episodes of mind-searing brutality are interspersed with delicate visions of immense compassion and humanity. No prefabricated answers are at hand; no situation or person is portrayed as wholly black or white; no clear path to redemption or salvation is evident. Immediately after completing a heartfelt prayer, a religious gathering morphs into a meeting intended to plan a violent attack designed to kill hundreds of innocents. One moment, a man is portrayed as crassly opportunistic and amoral; the next, he is full of genuine tenderness and caring.

These are only some of the true-to-life complexities that make Train to Pakistan a veritable masterpiece that shows Khushwant Singh's pen at the height of its powers.

The inclusion of Margaret Bourke-White's exquisite photographs makes this special anniversary edition an even more desirable acquisition. Like the story they so appropriately accompany, her unforgettable images are sure to touch your mind and heart forever.

Highly recommended; a real "must-have"!

October 31, 2007

Conversation about this article

1: Hans (Union City, CA, U.S.A.), October 31, 2007, 5:10 PM.

The film (now available on DVD) is excellent too!

2: I.J. Singh (New York, U.S.A.), November 01, 2007, 9:04 AM.

It seems to me that three life altering events have impacted Punjab and Sikhs during the past 150 years - the loss of Ranjit's Singh's kingdom, the partition of 1947, and the events of and around 1984. The partition of 1947 has received the least attention from historians and scholars. Much of what happened still remains undocumented and uninvestigated, even though records, documents and even personal accounts are still available. This is what gives "Train to Pakistan" veracity, relevance and timelessness well beyond what a work of fiction would normally enjoy. We now have a generation of Indians and Sikhs who are only marginally connected to or aware of 1947 and its importance. I surely hope that this new edition of a classic and its highlighting by sikhchic.com would renew our interest in our very colorful recent past.

3: Amrik Singh (New Delhi, India), November 01, 2007, 12:28 PM.

Great review! I missed the book the first time around. Thanks for bringing it to our attention now that it is available again. Sounds like Khushwant Singh has managed to capture some of the pain and horror of the monumental human tragedy that the Partition of Punjab and India was. Wish he and others will re-visit that era and write about it more ... it is a chapter of human history that has yet to be given its full and proper due in the pages that record turning points in human history.

4: Deepjot Singh (Sydney, Australia), November 19, 2007, 9:57 PM.

Can anyone please tell me if and where this film ("Train to Pakistan") is available in Australia?

5: Prabhjot singh (Mumbai, India), February 23, 2009, 3:22 AM.

My grandparents told me the following stuff before taking their last breath. He told me that he used to live in thr Pakistan part of Punjab. During partition, they were assured that at any cost the Punjab would not be partitioned. They remained there and then one day they were told, we can't help you? The Sikhs were in hell, with the Muslim mobs rampaging behind them and the Muslim refugees fleeing India who, having been looted and brutalized in India, took every single chance of taking their revenge for losing their family members and properties. There is so much to say ... Let God decide what he wants us to see in future, let him be the Savour.