Our Best Friends

Flora Annie Steel:

Punjab's Story Teller

Flora Annie Steel (April 2, 1847 - April 12, 1929) was an English writer.

She was the daughter of George Webster. In 1867, she married a member of the Indian Civil Service, and for the next twenty-two years lived in India, chiefly in the Punjab, with which most of her books are connected.

When her husband's health was weak, Flora Annie Steel looked after some of his responsibilities. She acted as school inspector and mediator in local arguments.

She was interested in relating to all classes of Indian society. The birth of her daughter gave her a chance to interact with local women and learn their language.

She encouraged the production of local handicrafts and collected folk-tales.

Her interest in schools and the education of women gave her a special insight into native life and character.

In 1889, the family moved back to Scotland, and she continued her writing there.

Some of her best work is contained in two collections of short stories:

From the Five Rivers (1893); and

Tales of the Punjab (1894),

while her most ambitious effort was her novel, On the Face of the Waters (1896), describing incidents of the Indian Mutiny.

She also wrote a popular history of India. Her later works were:

In the Permanent Way, and Other Stories (1897);

Voices in the Night (1900);

The Hosts of the Lord (1900);

In the Guardianship of God (1903);

A Sovereign Remedy (1906);

India Through the Ages; a Popular and Picturesque History of Hindustan (1908);

Mistress of Men : a novel (1918).

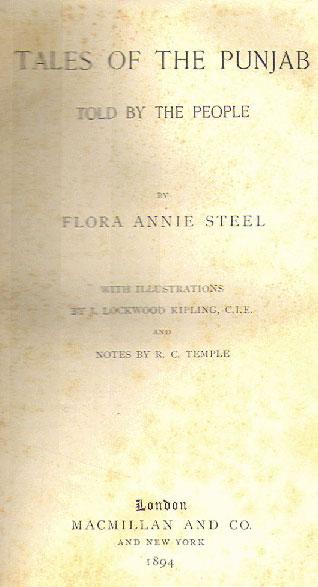

TALES OF THE PUNJAB

An Extract from the Preface by Flora Steele et al., in which she explains how she garnered these Punjabi Tales

Many of the tales in this collection appeared either in the Indian Antiquary, the Calcutta Review, or the Legends of the Punjab.

They were then in the form of literal translations, in many cases uncouth or even unpresentable to ears polite, in all scarcely intelligible to the untravelled English reader; for it must be remembered that, with the exception of the Adventures of Raja Rasâlu, all these stories are strictly folk-tales passing current among a people who can neither read nor write, and whose diction is full of colloquialisms, and, if we choose to call them so, vulgarisms.

It would be manifestly unfair, for instance, to compare the literary standard of such tales with that of the Arabian Nights, the Tales of a Parrot, or similar works.

The manner in which these stories were collected is in itself sufficient to show how misleading it would be, if, with the intention of giving the conventional Eastern flavour to the text, it were to be manipulated into a flowery dignity; and as a description of the procedure will serve the double purpose of credential and excuse, the authors give it - premising that all the stories but three have been collected by Mrs. F. A. Steel during winter tours through the various districts of which her husband has been Chief Magistrate.

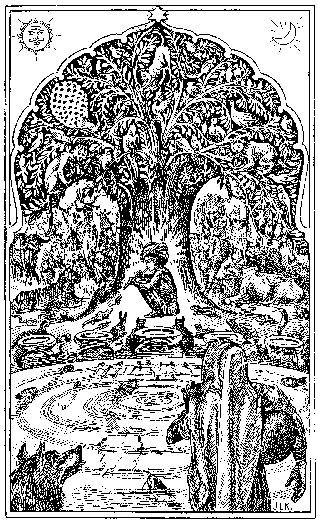

A carpet is spread under a tree in the vicinity of the spot which the Magistrate has chosen for his darbâr, but far enough away from bureaucracy to let the village idlers approach it should they feel so inclined. In a very few minutes, as a rule, some of them begin to edge up to it, and as they are generally small boys, they commence nudging each other, whispering, and sniggering. The fancied approach of a chuprâsî, the "corrupt lictor" of India, who attends at every darbâr, will, however, cause a sudden stampede; but after a time these become less and less frequent, the wild beasts, as it were, becoming tamer.

By and by, a group of women stop to gaze, and then the question "What do you want?" invariably brings the answer "To see your honour" (âp ke darshan âe). Once the ice is broken, the only difficulties are, first, to understand your visitors, and secondly, to get them to go away. When the general conversation is fairly started, inquiries are made by degrees as to how many witches there are in the village, or what cures they know for fever and the evil eye, etc.

At first, these are met by denials expressed in set terms, but a little patient talk will generally lead to some remarks which point the villagers' minds in the direction required, till at last, after many persuasions, some child begins a story, others correct the details, emulation conquers shyness, and finally the story-teller is brought to the front with acclamations: for there is always a story-teller par excellence in every village - generally a boy.

Then comes the need for patience, since in all probability the first story is one you have heard a hundred times, or else some pointless and disconnected jumble.

At the conclusion of either, however, the teller must be profusely complimented, in the hopes of eliciting something more valuable. But it is possible to waste many hours, and in the end find yourself possessed of nothing save some feeble variant of a well-known legend, or, what is worse, a compilation of oddments which have lingered in a faulty memory from half a dozen distinct stories.

TO THE LITTLE READER

by Flora Annie Steele

Would you like to know how these stories are told?

Come with me, and you shall see.

There! Take my hand and do not be afraid, for Prince Hassan's carpet is beneath your feet. So now! - "Hey presto! Abracadabra!" Here we are in a Punjabi village.

It is sunset. Over the limitless plain, vast and unbroken as the heaven above, the hot cloudless sky cools slowly into shadow. The men leave their labour amid the fields, which, like an oasis in the desert, surround the mud-built village, and, plough on shoulder, drive their bullocks homewards.

The women set aside their spinning-wheels, and prepare the simple evening meal.

The little girls troop, basket on head, from the outskirts of the village, where all day long they have been at work, kneading, drying, and stacking the fuel-cakes so necessary in that woodless country.

The boys, half hidden in clouds of dust, drive the herds of gaunt cattle and ponderous buffaloes to the thorn-hedged yards.

The day is over, the day which has been so hard and toilful even for the children - and with the night comes rest and play. The village, so deserted before, is alive with voices; the elders cluster round the courtyard doors, the little ones whoop through the narrow alleys.

But as the short-lived [Punjabi] twilight dies into darkness, the voices one by one are hushed, and as the stars come out the children disappear. But not to sleep: it is too hot, for the sun which has beaten so fiercely all day on the mud walls, and floors, and roofs, has left a legacy of warmth behind it, and not till midnight will the cool breeze spring up, bringing with it refreshment and repose.

How then are the long dark hours to be passed? In all the village not a lamp or candle is to be found; the only light - and that, too, used but sparingly and of necessity - being the dim smoky flame of an oil-fed wick. Yet, in spite of this, the hours, though dark, are not dreary, for this, in a [Punjabi] village, is story-telling time; not only from choice, but from obedience to the well-known precept which forbids such idle amusement between sunrise and sunset.

Ask little Kaniyâ, yonder, why it is that he, the best story-teller in the village, never opens his lips till after sunset, and he will grin from ear to ear, and with a flash of dark eyes and white teeth, answer that travellers lose their way when idle boys and girls tell tales by daylight.

And Naraini, the herd-girl, will hang her head and cover her dusky face with her rag of a veil, if you put the question to her; or little Ram Jas shake his bald shaven poll in denial; but not one of the dark-skinned, bare-limbed village children will yield to your request for a story.

No, no! - from sunrise to sunset, when even the little ones must labour, not a word; but from sunset to sunrise, when no man can work, the tongues chatter glibly enough, for that is story-telling time. Then, after the scanty meal is over, the bairns drag their wooden-legged, string-woven bedsteads into the open, and settle themselves down like young birds in a nest, three or four to a bed, while others coil up on mats upon the ground, and some, stealing in for an hour from distant alleys, beg a place here or there.

The stars twinkle overhead, the mosquito sings through the hot air, the village dogs bark at imaginary foes, and from one crowded nest after another rises a childish voice telling some tale, old yet ever new - tales that were told in the sunrise of the world, and will be told in its sunset.

The little audience listens, dozes, dreams, and still the wily Jackal meets his match, or Bopolûchî brave and bold returns rich and victorious from the robber's den. Hark! - that is Kaniyâ's voice, and there is an expectant stir amongst the drowsy listeners as he begins the old, old formula -

"Once upon a time ..."

March 6, 2009