Fiction

Emperor:

Duleep Singh & The Company

Chapter IV

A Serialized Hiistorical Novel by T. SHER SINGH

Previous and subsequent chapters are accessible by clicking on the DAILY FIX icon on the HomePage.

CHAPTER IV

Once back in the camp in Firozepur, Lord Auckland and Colonel Wade turned into whirlwinds of activity: meeting, dictating, studying charts, mapping strategy, sending out couriers in every direction.

I had time on my hands. My thoughts turned to Lahore. I felt an emptiness in the pit of my stomach for having been away from the city. I moped for a while, mulling over all that I had missed in just these last few days.

I mused that a mere 130 years had passed since the tenth and last of the blessed teachers of our Faith had ascended from his earthly sojourn. I wish I had been alive then, to have had a single sight of him, to have been able to walk in his shadow only once. I have met men who have actually talked to those who had served him. Alas, I was born a few generations too late for the great blessing they enjoyed.

But then, I did have the good fortune to be alive in another golden era and had actually seen Runjeet Singh, the greatest mortal our nation has produced since. Oh, how I wish I had been there that day in the walled city, the day they took the Lion on his final journey.

I fled to the stables. There’s no better place to catch the latest gossip. You need to know what’s going on in the world? That’s where you go.

I have talked to many who were in Lahore, pestered them for every little detail. And later, when I did get the opportunity to visit the court again -- though long after its heydey was over, I’m afraid -- I grilled those I knew had been there amidst the heaving and jostling humanity on that fateful day.

They say every moment in time is the fruit of all that is past … and the seed of all that is to come.

So was that eventful day.

Prince Kharak Singh -- rather, Maharaja Kharak Singh, I should say now! -- had with his own hands washed the body of his father. Then dressed it in silks, and covered it with jewellery. A pride of generals and noblemen then carried the bier out to the courtyard on their shoulders.

Lying in wait was a ship which would take the Sarkar on the final lap of his journey.

A towering ship carved out of sweet-smelling sandalwood, with gold and silver covering every inch of it, its inlaid firmament of precious stones sparkling like a night-sky. Large sails of silk and pashmina rose upwards, flapping from the masts, each also wrapped in the fabrics, in the morning breeze. Soft, intricately embroidered shawls -- the hallmark of the court’s furnishings for four decades! -- lined the interior.

The funerary ship had been commissioned several weeks earlier, in preparation for what all knew was but around the corner.

It took a mob of courtiers to carry the bier on board, where it was placed in the centre, on the raised deck.

Stretching out from where this scene was unfolding, a double-line of infantry, each soldier in the full ceremonial regalia of silks and jewels always demanded of them by the Sarkar, stood in sombre attention as it wove its way past the ancient Pearl Mosque, across the grounds facing the Great Court of the People, down the steps, through the gate, and out into the bazaar.

Word had spread like wild fire the previous evening, the moment loud wailing was heard from the queens’ courtyards, even above the din of clouds of parrots returning to their trees at day’s end. The locking of the gates and the boom of cannons from the ramparts had confirmed the sad news to the populace.

The city had not slept that night.

People poured out of their homes and rushed to the walled city. They flocked outside the gates. From balconies, ledges and rooftops, trees and walls, wherever a perch could be found, anxious faces peered up at the ramparts of the fort-palace, hungering for a final sight of the man who had brought peace and prosperity to the lives. The streets and bazaars were swollen until they could take no more, as even more poured in from the countryside.

When the three Bhai Sahibs of the Royal Court had administered the final rites and followed the bier into the courtyard, one of them - Bhai Gurmukh Singh - had briefly stepped into the pavilion by the north wall, dug through the crowd therein, to take a glimpse through the lattice window overlooking the Roshnai Gate, past which the cremation was to take place.

It was a few hours before they would get there, but noise from the multitude below was already a crescendo. There were people as far as he could see, all the way into the sprawling Great Mosque in front of the Fort. People everywhere. On its walls and on each of the minarets, even the distant ones.

It looked like there couldn‘t have been a single soul left in any home for miles.

This was a man they had loved like no other. They had tasted his generosity, his kindnesses and compassion, and seen in him one of their own, an unlettered, uneducated man who had risen to the pinnacle of power, but had kept his feet on the ground.

How could they forget that when he became master of all of Punjab, he had refused a coronation, and even scoffed at being called Maharaja -- the Emperor -- though the world did. He took on no grandiose titles even when he, for example, brought Kashmir under his wing. Or when he conquered the oppressive Afghans. Or when he had eye-balled the scheming English into accepting the Sutlej as a boundary to their ambitions.

They remembered that in his own court he had insisted on being called simply ‘Sarkar‘: the “government“. With no further honorifics or titles.

Any man, woman or child could enter the court and speak to the Sarkar. For the government itself, he had insisted, was Sarkar Khalsa ji” - the Government of the People. His court was “Darbar Khalsa ji” - the Court of the People.

The ominous day in 1801 he assumed the spartan title -- and responsibilities -- of “Sarkar,” he had proclaimed: “I promise to serve you, the people, and no other. In the name of Nanak and Gobind Singh!” The images and names of the Gurus were the only ones that adorned the coins of the kingdom, never his own.

Sohan Lal, the man who meticulously reported the daily goings-on in the Sarkar’s court, once showed me the proclamation that the Sarkar had made that day four decades ago.

He had looked tall despite his short stature, dashingly handsome despite his pock-marked facial features and a blind-eye, as he had sat on his horse outside the Alamgir Gate and made a pledge to the crowd: he would perform six duties, but only as long as the people wanted him to be their sarkar, not a day longer:

Bring law and order. Save them from foreign invaders. Bring prosperity to the land and people. Unite the Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs under one banner. Deliver justice impartially to all, rich or poor, high or low. And give all -- Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs -- positions of power, but solely based on merit.

Each of the multitude that had gathered outside the same gate 38 years later knew that he had kept his promise. And they knew in their heart of hearts that they would not see another like him.

* * * * *

The funeral procession was about to begin when the attention of the royal mourners was drawn to the queens’ apartments.

Another small procession had emerged and was heading towards the funerary ship. Quick words were exchanged, and a number of the ministers rushed towards the female entourage.

It appeared that a few of the queens had decided to perform “suttee”, the Hindu practice prevalent in some of the neighbouring kingdoms, requiring widows to immolate themselves on their husbands’ funeral pyre.

The Sikh Bhais, being responsible for the Kingdom’s religious matters, were enraged. It was a barbaric practice denounced and prohibited in Sikhdom, they protested. Certainly, the Sarkar had never permitted it within his dominions.

The Fakir -- Runjeet’s Prime Minister -- too tried to dissuade the women, but withdrew quickly. “I am Muslim,” he said to the Bhais, “and you are Sikh. We have to tread softly, we’re dealing with religious sensibilities. Because the queens who wish to suttee are Hindu. They claim it is an observance required by their faith, and we have no say!”

Matters had got exacerbated when Hindu priests had spoken to the women earlier that morning. They had said that if any of the Hindu widows were childless, it was their duty to suttee: it would guarantee them every wish fulfilled in the next life; if they didn’t, they would be cursed in this life, and for all eternity thereafter.

The Bhais turned to Dhyan Singh, the new minister. Himself a Hindu, he had not helped things any. He fell at the feet of the women, hailing them for their great sacrifice, and then offering to suttee with them. That created its own commotion, with one and all now trying to dissuade Dhyan Singh.

“You have promised the Sarkar to guide the new Maharaja,” they implored. His brothers held him back as the women moved forward.

Runjeet Singh’s Empress -- the Sikh Rani Raj Kaur, Kharak Singh’s mother -- had predeceased her husband. So had her predecessor in rank, Rani Mehtab Kaur, also a Sikh, and the mother of the younger prince, Sher Singh.

Which had left a Hindu princess from Kangra -- Rani Mahtab Devi -- the senior in-charge of the Queens’ apartments.

Now four of them had decided to suttee. Each was a daughter of a Hindu raja from a distant fiefdom who had been offered in marriage to forge a political alliance, but having done so, had continued to live in her ancestral home, but supported by the Sarkar.

Now, childless and widowed, they had rushed to Lahore, and were not to be deterred from their mission.

Thus was added a heart-rending sight, to the further dismay of a nation of sunken hearts.

The ship was lifted by a hundred soldiers clad in white and began its circuitous journey, followed by another hundred like them, poised to take over the load at regular intervals.

The new Maharaja followed right behind on foot, surrounded by the entire court. Each in white, without jewellery or ornamentation, each bare-footed.

A group of Sikh minstrels was singing hymns from the Sikh scriptures, accompanied by drums and cymbals, sarangis and chimtas.

Behind them, similarly, a Hindu contingent was chanting bhajans. And a group of mullahs singing verses from the Quran.

And then, a sight never seen before in public. A palanquin with the senior-most suttee queen. The curtains were drawn back. The face too was bare of any veil. In a white sari. Closely followed by a retinue of her attendants.

This scene was repeated thrice, with each of the other suttees. At the end of this procession in white walked seven more women. Girls, really. They were the personal attendants of the four queens, and had also opted for suttee, once again over the angry protests of the courtiers.

Thereafter followed what appeared to be an endless march of the regiments, each bedecked in its ceremonial colours, in the formations they had been taught so meticulously by the European generals Runjeet had hired. Each general marched at the head of his unit.

Nagaras -- war drums -- rang out not only from within reach regiment, carried on festooned elephants and camels -- but different parts of the fort itself. Other drums could be heard from the city below, the beats wafting up and over the ramparts.

Punctuating all of this, as the endless column snaked its way through the palace and fort buildings, were the cannons being fired in salute from the outer north-eastern walls facing the parched bed of River Ravi.

When the ship reached slowed down to maneuver into the already clogged bazaar, the four palanquins were lowered to the ground and the women stepped out. A collective gasp was heard from the crowd.

They began to walk, each shockingly bereft of veils and fineries. In plain white, without any ornaments, bare-foot. Walking immediately in front of each of the four was a man facing them, walking backwards. He was holding up a mirror. So that each suttee could check her countenance at all times to ensure that she betrayed no fear, no regret, no doubt.

They were to show no emotion. They were to go to their deaths with no weeping, no wailing, no crying, no screaming, even as the fire would consume them. Otherwise, they had been told by the brahmins, their sacrifice would be futile and unworthy.

Beside each suttee was an attendant holding up a basket. Of jewels. Every few steps, the suttee would dip into the basket, pickup a handful -- her own jewellery -- and throw it into the crowd.

Elsewhere, at regular intervals, gold coins and ornaments made of gold and silver and precious stones were being tossed to the crowds: acts of charity meant to ease the deceased’s journey into the beyond.

The sun was getting higher and hotter. Which ensured that the procession kept up its pace. It took hours, though, to negotiate the quarter-mile.

Finally, past the Pavilion of the Twelve Arches and the Alamgir Gate, it turned left and then swung into the Roshnai Gate, towards the mountainous pyre of sandalwood and sweet spices awaiting the final destination of the ship.

The ship in its entirety was then lifted in perfect precision by the soldiers to the top of mound.

As the suttees walked past the noblemen, they were once again begged and implored, chided and scolded, for their planned suicide. They showed no reaction, and continued on their path without a flinch. They climbed the ladder, one by one, until they were on the deck.

The Bhais who had assembled atop the mound to do the final ardaas again beseeched the women. The latter simply ignored them and proceeded to position themselves around the body. Mahtab Devi settled down next to the head of the Sarkar, and then lifted it and slid under it so as to nestle it in her lap. The other three huddled around her. The seven servant girls sat down in a cluster at the feet.

The Bhais came down, and Kharak Singh then ascended the ladder. He was not sure of foot and had to be assisted all the way. Atop, he lifted the silks and shawls that covered his father's body, leaving him in the simple clothes he was always at home with, and tossed them, one by one, into the crowd. He did the same with all the jewels that adorned the body. He then covered it with straw and strips of sandalwood.

He bent over and tried to talk to the suttees but the chants of the brahmins nearby, intentionally raised in volume, drowned his entreaties. He looked at the young girls at the other end. Their eyes were shut in prayer. He shook his head in despair: this had turned into a tragedy of multiple proportions.

Suddenly, a scuffle seemed to have broken out below.

The Dogra Dhyan Singh, it appeared, was trying to clamber up the ladder, loudly wailing that he too would be a suttee. His brothers and son were holding on to him. They gently lifted him off the rungs, brought him down and pulled him back until he once again stood amongst them.

After Kharak Singh came down, the Dogra seemed to try to break away from his brothers again. Twice. And twice they held him back.

Sentries went around valiantly attempting to widen the circle of humanity around the ship. It was an exercise in futility.

Finally, amidst rising prayers and chants, a flame was flung by Kharak Singh onto the pile from a distance.

For a few moments, nothing happened. And then, a ball of fire arose and within seconds engulfed the entire ship.

The flames did the trick: the crowd staggered back, but by a grudging inch by inch.

A thunderous cry, the likes of it never heard before or since, I am told, enveloped the hundreds of thousands who saw the white sky turn orange. If you had a keen ear, you could have heard the booming “Akal! Akal! Akal!” too of the Akalis: "Hail! The Timeless One!"

No one heard the cries of the women, though. No one could have, even if there had been any.

Gradually, the crowd went silent. The drums continued their dirge, egged on by the thump and roar of the mourning cannons.

A crowd of Sikhs gathered in the shrine a hundred yards away - marking where Guru Arjan had been tortured to death on another hot day more than two centuries before - continued their recitation of Arjan’s own verses: The Psalm of Peace.

The fire raged for hours.

The crowd remained seemingly motionless, except to shuffle back further as the fire progressed, to escape the flying embers.

It was the hottest day Lahore would ever see, someone cried out.

And then, suddenly, a shadow appeared over the crowd: a cloud, hovering straight above the burning bier. A few drops of rain fell on the crowd.

Was it a sign, an omen, some whispered.

Two doves appeared through the smoke, circled the flames dizzily, and then flew right into the fire.

* * * * *

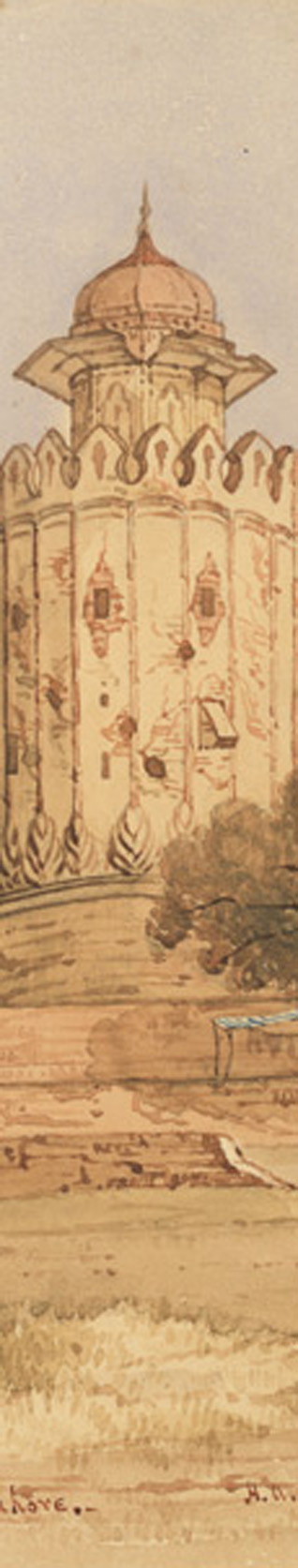

High above all of this, immediately behind the crowd, rise the outer walls of the fort. Further behind it, past the moat, is the inner wall -- the famed Picture Wall, decorated with framed inlays of intricate flowers and animals in bright colours, within the stone -- which rises a hundred feet into the air. It guards the Emperor’s apartments, his palace, his fort.

Crowded behind the latticed windows hovered the household, grief-stricken … and worried about the uncertain future.

Removed from the crowd, a small cluster stood separate, huddled within a balcony. The window was too small to allow more than one of them to peek through to catch a glimpse of the goings-on down below.

Looking through the window was a young, strikingly beautiful woman. She held a child, deftly balanced on her hip, as she observed the funeral.

Of her husband.

The woman was Rani Jind Kaur, the youngest of Runjeet Singh’s queens, considered insignificant by the court and courtiers alike, and therefore relegated to the periphery of the household. And ignored.

Perched in her arms, barely a toddler, was the youngest son of Runjeet Singh.

"Duleep Singh", his father had named him only the year before.

To be continued ...

COPYRIGHT: sikhchic.com

December 4, 2012

Conversation about this article

1: Sukhindarpal Singh (Penang, Malaysia), December 05, 2012, 8:53 PM.

One Sher describing the last moments of The Sher ... WOW!

2: Raj Singh ( Montreal, Quebec, Canada), December 06, 2012, 1:18 PM.

Love the foreshadowing. The author has done a fantastic job with his writing style. I feel like I'm going back in time, with a front row seat to history.