Fiction

Let Your Mind Be

Part III

ROSALIA SCALIA

Continued from yesterday ...

Early the next morning, the phone jangled, the first of series of calls from neighbors upset about the presence of a commercial

vehicle in the drive way. Throughout the day, the week, two weeks, telephone complaints mounted.

”It’s not my damned truck,” Amrit yelled at callers, frustrated that the truck that nearly killed him had now become a further source of aggravation.

Pinkie refused to erase the voice mail complaints or pay the growing pile of parking tickets, opting for court dates. Fines and penalties mounted and so did the tension between them, between them and their neighbors, and his parents.

Amrit craved that 15-second blissful rush but fought it, his cough a painful reminder of damaged lungs. He cut, stirred, mixed and cooked to avoid temptation, his rising anxiety transformed kitchen counters, the table and the refrigerator into surfaces overflowing with pakoras, samosas, rotis, stuffed and plain naans. Before long, their extended families and friends joined them for dinner since he cooked enough for two langars, and by June, family and friends began gathering regularly for dinner around the backyard picnic table.

“Did anyone check the truck to see if any ice cream is in it?” Qurban asked in mid-summer.

Amrit and Pinkie glanced at each other, then ran to the driveway, opening the truck door for the first time since Harris parked it. The odor of putrid ice cream gagged them, and a cloud of flies buzzed inside.

“Crap!” Amrit shouted. Everyone scrambled to kill flies, scrubbing and disinfecting the truck before hosing the driveway, working well past midnight.

“Maybe we should just sell the thing,” Amrit said later after everyone left. He and Pinkie lay exhausted in bed. “What do we gain by forcing him to take it back?”

“He can’t arbitrarily decide the outcome for his negligence. Dealing with the truck is a finite inconvenience. After-effects of

injuries can turn debilitating. What if your leg develops rheumatism or crippling arthritis? You’ve been recuperating and out of work for months. That should be compensated. You could have been killed. What then? Forcing the truck on us is insulting,” she said, drifting to sleep.

“Where do you think compensation will come from?”

Already asleep, Pinkie didn’t answer. Awake, as Amrit watched the digital clock’s red numbers rotate, he recalled his first high. Back in India when he’d been visiting Biji, they’d gone to the Widows’ Colony where his grandmother visited the ladies, and he played cricket with the boys in the lanes there. Boys like Raju and Gurmeet and Tihar, sons of rickshaw drivers, of chai-wallas, and of workers at his grandfather’s hosiery factory, all boys orphaned like his cousins on that crazy, mob-filled day. The men who’d injected him laughed as the smack rush overcame him. He’d smiled, too, nodding, not realizing that over time the joy would diminish, and he’d need increasing amounts to feel it, and that he’d spend his life and money chasing it.

Raju, then 10, had overdosed before his 14th birthday, the first to die. Biji’s letters had chronicled the boys’ deaths, one by one, from overdoses, from having been beaten by drug peddlers, or by police, or by people who’d caught them stealing, or killed in jail.

One day, after he’d chopped his hair, he came home to his father weeping over Biji’s most recent letter saying Taya ji’s two sons, Mahinder and Surinder were both dead from drugs. Finally he’d told them the truth, about the men who’d first injected him, and for the first time since he’d cut his hair, his parents held him, forgiving his sin, saying better to have a live son with missing hair than a dead one.

“Bastards!” his father had shouted, shocking him. “Sardars’ sons can’t demand justice for lost lives or stolen property if they’re addicts,” his father had yelled, lobbing his shoe at the living room wall. “Mahinder and Surinder were targeted because of the factory, I’m sure of it. Amrit happened to be in the wrong place at the right time.”

Amrit had entered his first rehab center shortly thereafter, but he’d slipped, within a month of returning, thus beginning the cycle of failed rehabs. His stomach clenched. He nearly failed again, if it weren’t for Qurban. Amrit felt neither dead, nor alive, but stuck in between. Unable to sleep, he retreated to the kitchen where he dumped chickpea flour into a large bowl and began mixing batter with his hands for another batch of pakoras. He decided on samosas too, thinking he’d exhaust himself from cooking, a distraction from thinking about the dead, about the losses, and dumped a bag of potatoes into the sink. He peeled potatoes, chopped onions, cleaned and diced vegetables, poured oil into two frying pans, concentrated on the individual preparation steps for pakoras and samosas and cooked to avoid remembering Raju and his cousins.

“Fuzzy, you’ve got to slow down with all this!” Pinkie said, yawning. In her pink nightgown and robe, she resembled a tiny, frail bird. Already, she was preparing for work. “Were you cooking all night? The entire family is getting fat! Except you!”

She surveyed the trays of pakoras and samosa lining the kitchen counter.

“Ok, we’ll sell it.”

“You changed your mind?” He dipped the last of the broccoli florets, onion rings, mushroom tops into the pakora batter to fry.

Pinkie sighed. “I hate to see you hurting like this.” She spooned instant coffee into a mug, filled it with water, sugar and cream and stuck it in the microwave.

“Too bad we can’t put all this food in that stupid truck and give it away, a rolling langar,” Amrit said, washing batter off

his hands, neglecting to towel them dry.

“Langar is for the gurdwara,” Pinkie said, matter-of-fact.

Anxious to finish, he dropped the remaining batter-covered broccolis into the hot oil. Water from his hands dropped into the pan, splattering hot oil in every direction, burning his arms and hitting the corner of his right eye. “Shit,” he shouted, rushing to the sink to splash cold water into his eye and over his arms.

“Watch the pakoras,” he told Pinkie. “Don’t let them burn. There’s potato samosas you can have for breakfast.” Head bent into the sink, turned on the cold water and thrust his face under the faucet.

The sound of the running water coupled with the sting from the burns transported him to Delhi, to the Rakab Ganj Gurdwara, to the day he desperately tried to forget. He was 10 - like Raju - with everyone he’d known huddling inside, locked in against people outside, carrying sticks and clubs, screaming “Kill the Sardars!”

“What harm can come if I can ask them nicely not to destroy this sacred spot? They can reason, can’t they?” Papa ji, grandfather, had asked Biji, who’d begged him to stay inside. Papa ji touched Biji’s shoulder, but fixed his eyes on Amrit, whispering, “Sing, and listen, and let your mind be filled with love. ‘dhukh parehar sukh ghar lai jaae'. Your pain shall be sent far away and peace shall come to your home.”

After Papa ji disappeared through the front door, Amrit never saw him again. Taya ji watched Papa ji through the front window, and then he too ran outside. Watching through the window, his father and others had cried out. Men holding his father prevented him from running outside, screaming , “Think of your sons!”

Then something happened, and his father and some men dashed outside with a carpet, half carrying, half dragging only Taya ji inside.

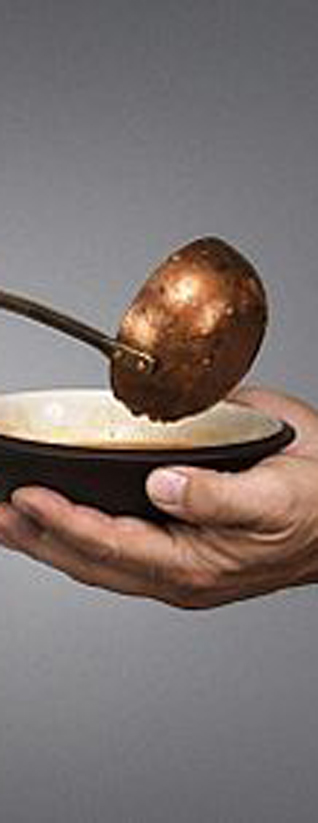

Taya ji’s entire body was scorched. Biji had wept and prayed. Someone had opened the faucet in the langar kitchen. The swoosh of water running through the pipes drumming the sink and Biji’s hoarse-voiced prayers rose above the din outside. A chain of hands had passed water in glasses and jars to Biji, who poured it over Taya ji.

“Everything is Yours, O Inner-knower, Searcher of hearts; You are the Lord God of all,” Biji had repeated, weeping, pouring

water over Taya ji, her first-born son inert on the carpet. From his mother’s lap, Amrit had spotted a single circle on the bridge

of his Taya ji’s nose that still looked smooth, brown, and unburnt.

Just as he reached for that spot with his pointer finger, Biji had slapped his hand away with such force, it thrust him onto the floor, and he’d wailed, his cries converging with the sounds of running water and Biji’s keening prayers.

Now, running water swooshed through his own sink’s pipes, gushed onto his face, drummed the basin, immobilizing him. His nightmares, restlessness, the painful vortex that had ensnared him with the smack, were bound by an invisible but formidable thread to that day at the Rakab Ganj Gurdwara when both Taya ji and Papa ji had been murdered and where he and the others remained trapped inside for endless hours, protected only by the strong main doors keeping out the mob.

Cool water turned icy, and he pictured Taya ji’s charred body, understanding Biji’s impotent protection of her dying son. Now bent over the sink, icy water gushing over his face, he submitted to the suppressed anguish of the events at the Delhi gurdwara that no one spoke about since, events that rippled across time and geography, weighting the trajectory of his life, and he wailed as if he were 10 again.

“Fuzzy!” Pinkie hurried to him. She shut the faucet, wiped the water from his face with her pink robe, wrapped his hands in a kitchen towel, and held his gaunt, shivering, body. A coughing jag hit him, and he bent forward, hacking into a dish towel. No blood.

“I saw my uncle die, murdered,” Amrit said after a few minutes. “Papa ji, too, murdered.”

“Qurban told me,” she said, hugging him. “I know everything. Qurban told me long ago. Everything will be alright.” Surrounded by a mountain of patakas, snacks, she held him close and they rocked. “We can’t eat all this food,” she said.

An idea struck him. “What’s in the driveway?”

“You mean that monstrous problem of an ice cream truck?” Pinkie asked.

“A rolling langar,” he said.

Pinkie stepped back, smiling. “I think you found a job! Living in your parent’s basement has allowed us to build a substantial savings. We could do it, a langar on wheels.”

Amrit considered this. “I’d need help. Lew Harris might be just the man. He can have his livelihood back, just not as a Good Humor Man.”

“Why not both of you take a small salary. There’s two gurdwaras in Baltimore. Maybe members from both could be on a board, and people from both can volunteer,” she said. “You can make this happen.”

Torpor gone, Amrit researched companies on the computer, found merchants willing to reduce labor costs for sweat equity. He replaced the ice cream truck’s freezers with stainless steel, propane fueled grill tops. Keeping a small freezer and one of the soft ice cream machines, he installed a mini stainless steel microwave, sink, and other cooking appliances. He talked to food suppliers, restaurant owners and to the councils at both of the city’s gurdwaras.

He fished Law Harris’ card from his jacket pocket and visited the old man. He spirited one of Pinkie’s favorite pink blouses out of the house and returned it before she could notice.

Nearly a year after the accident, he became too busy to shave or to worry about hair cuts, and he began to pull his growing hair into a short pony tail. He borrowed, first Qurban’s bandanas, and then his patkas. He left the house early in the mornings, returning just before midnight, exhausted.

When the truck conversion was completed, board members representing both gurdwaras in place, paperwork giving the enterprise non-profit status filed in in order, volunteers from both gurdwaras organized and ready, Amrit drove the former ice cream truck - now painted pink in honor of his wife, the genius behind the paperwork - to Lew Harris’ house and blasted the horn twice.

The old man climbed aboard, and Amrit pointed the truck toward the interstate and downtown.

“I don’t understand exactly how this enterprise is going to work, giving food away for free, but I’m sure pleased to have a job again,” Harris said from the seat in the back.

“Think community kitchen, community meal, where everyone eats and everyone is equal,” Amrit said. “It’s all vegetarian so that everyone can eat, regardless of dietary restrictions. It’s rice, flatbread and lentils.”

“What about a profit margin to buy the food to give away?” Harris asked.

“The food will come,” Amrit said, smiling.

“You sure sound confident about that,” Harris said, sounding skeptical. “What about truck repairs and tires and maintenance?”

“Langar has been going on for more than 500 years, but maybe this may be the first mobile langar in the world,” Amrit said. “Some funds would be earmarked for maintenance and some mechanics from the gurdwara will oversee the truck .”

Merging onto the interstate, Amrit glanced in the rear view mirrors, and was shocked that the man looking back at him sported a nascent beard with a scandalous number of gray streaks.

His face appeared fuller. Qurban’s patka covered his head. The aroma of rotis, daal lentil soup, and basmati rice permeated the inside of the truck. Amrit shifted it into gear and switched on the loudspeaker to play a shabad, taking the downtown exit to his first stop by the park in front of the University of Maryland Medical Center. He passed Lexington Market, a solid reminder of his addiction.

“What funds?” Harris asked.

“Don’t worry,” Amrit said. “That will come, too.” He turned east onto Baltimore Street toward the park across the street from University of Maryland Medical Center entrance where Pinkie - and an army of volunteers from the city’s only two gurdwaras - women in salwar-kameezes and men wearing colorful turbans - cheered and waved from the corner like festooned solider-saints-servants, God’s workforce. He slid the monstrous truck into a waiting space, and one of the volunteers who’d once helped bring a langar to a train station in India, organized the others and the system to feed anyone who wanted to eat.

The loudspeaker’s gurbani music drew a crowd, and per Pinkie’s advice, volunteers circulated pink papers bearing a neatly typed explanation of langar with the food.

Pinkie burst through the front door. Smiling, she examined the newly-converted interior, inspected the refrigerator’s knobs and buttons. Harris, already fast at work, handed a large tin of rotis and some paper dishes to one of the turbaned volunteers through the side window. Other volunteers boarded and set to work, everyone knowing their jobs.

“Baltimore will never be the same after this! There’s no mobile soup kitchen, but thanks to you, now a rolling langar supported by two gurdwaras,” she said, smiling.

“Not just me. Look around,” he said. “A collective ‘we’ and Lew, too.”

From her purse, Pinkie pulled a plasticized prayer card of the Tenth Guru and tucked it into a crevice above the driver’s seat.

Lexington Market - three blocks north - broadcasted smack’s seductive siren songs, but Amrit hoped they’d be overpowered by the gathering of the sangat - people, young, old, black, white, rich, poor, coming to eat as equals - and Papa ji’s voice reciting his prayers aloud, producing a persistent, palpable echo in his ears: Sing, and listen, and let your mind be filled with love.

‘dukh parehar sukh ghar lai jaae.' Your pain shall be sent far away and peace shall come to your home.

CONCLUDED.

June 7, 2012

Conversation about this article

1: Baldev Singh (United Kingdom), June 07, 2012, 11:24 AM.

Vaah, Vaah! WOW! What an ending! What an ending! Ms Scalia has taken a tragedy and transformed it into a tale of gurmat triumphing over the pure evil of political-sectarian violence and their scars, both physical and mental. Thank you, Ms Scalia.

2: T. Singh (San Francisco, California, U.S.A.), June 07, 2012, 1:42 PM.

WOW, what a moving story. So hard to express. I have so much respect for the protagonist and his wife. You have taken me back to 1984. You made me laugh, cry and shocked and, in the end, happy for him and his family. Great idea, the mobile langar. If anyone starts it, please let me know if I can do anything to help. Keep up the good work. God bless you. Thank you for sharing this wonderful story with all of us.

3: Satvir Kaur (Boston, MA, U.S.A.), June 08, 2012, 3:27 PM.

The three days that I read this over, I was always waiting for the next part. I loved the ending but am sad that is finished now. Is this a true story or based on one? Waiting for more ...

4: Lucky (Catonsville, Maryland, U.S.A.), June 09, 2012, 10:17 AM.

What a great story of redemption! The fact that he battled addiction, found love, and his way back to a sincere spiritual path - is wonderful and encouraging! It's like my parents always told me - no matter what you've done, the gurdwara is like your parent's home, you can always go back and always be welcomed. You can ask for whatever you need - God is limitless in his love. You just have to be really wanting it. P.S. - I really loved Pinkie!

5: Rosalia Scalia (Baltimore, Maryland, U.S.A.), June 18, 2012, 11:09 PM.

Many thanks for reading my story. Satvir Kaur: I am humbled by the high compliment of asking if the story is real. The character, Amritpreet Singh, is completely fictional as is the story. There is no rolling langar in Baltimore, Maryland. Can't explain my stories with Sikh characters except to say they are a labor of love. Thank you all for reading it.