Cuisine

Home is Where ...

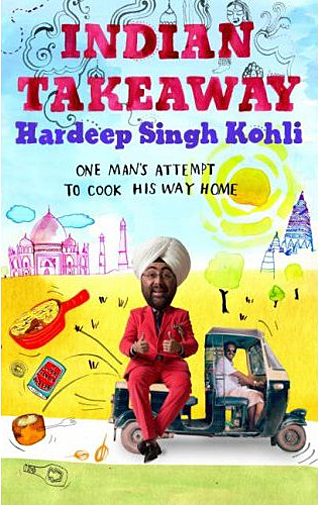

by HARDEEP SINGH KOHLI

The son of Punjabi immigrants in working-class Glasgow, Hardeep Singh Kohli suffered from identity confusion - was he really any more than a Scot in a turban?

On paper, my parents have very little in common - my mother is working-class immigrant Indian, my father lower-middle class from the heart of the Punjab. Yet somehow, forty or so years after their arranged marriage, they are still very much together.

As for me, I'm Scottish, and am indebted to my father for moving to Scotland, since being Scottish has improved my life immeasurably. I am funnier, wittier and better-looking for it.

My outward appearance may be Indian but my mind, my heart and my stomach are very much from Glasgow. English is my first language, by quite some way. Yet, as a turbaned Sikh, Indians expect me to be a fluent Hindi and/or Punjabi speaker. It seems wherever I go in the world, the expectation of who I might be is never in sync with who I actually am.

It's time to ask my dad some searching questions, and there is no better time than when he has a freshly made mug of tea in his hand and a plate of biscuits on standby. He is captive.

"Why did you leave India, Dad?" I asked, more in hope than expectation.

"To better myself. For a better life for you," he replied.

"But you didn't even know you were going to have a family when you left."

"We didn't ask so many questions in those days, son." He sipped his tea. "Life was much easier then. Why are you asking all these questions?"

"It's difficult to explain, Dad. I feel like something is missing in my life. A reason for being." I looked at him.

"If you think something is missing, then you should try and find it."

I decided to travel to India on my own and discover it for myself, cooking in each town, discovering a little of India and hopefully a lot of myself. It was time to go home. Wherever home might be.

In my repertoire I have a number of powerful classic British dishes. This is food to fall in love over, food to fight over, food that I hope will make me friends across a subcontinent. Food is a massive part of my life. When I'm not cooking it, I'm eating it, and when I'm not eating it, I'm thinking about it. I plan my life around meals. I love food, and for its sins, food loves me.

When someone once asked me why I was so obsessed with food, I struggled, before it dawned on me: as a child, the only aspect of being Indian that the wider society seemed to celebrate was our food. Like every other British city, the Glasgow of my childhood loved Indian food. Even racists liked our food. It was the only aspect of being Indian that garnered any positivity.

Ironically, despite the plethora of restaurants around us, we never ate out much as kids. We were the offspring of immigrants. Still, to this day, I have absolutely no idea how my parents ran a house, fed us, clothed us, took us on holiday and paid the mortgage.

Both my parents worked: my mum in the shop, my father long and irregular hours as a teacher in a school for delinquents. And yet, even though we didn't cuddle up in the lap of luxury, I never felt that I went without. We had what we needed. And what we didn't need, thanks to the fiendishly fiscally astute way my mother planned weekly meals, was anything more than one night of dining out a year.

So that's what we got. A little tandoori restaurant in Elmbank Street in the heart of Glasgow, the same street on which, years later, I would meet the woman who would become my wife.

We would never have gone out to eat food that Mum could have made at home. That would have been pointless. Why pay over the odds for home food? But Mum didn't have a tandoor and no matter how good her spicy yoghurt mix, no matter how well she balanced the chilli and the lemon, no matter how infused her chicken became, it never ever tasted like it had come out of a clay oven.

So we went to this little place and gorged on tandoori food. I remember it being delicious and my father being very excited about it. It was only years later that I fully comprehended how much my dad missed the food of the Punjab, the food of his home. We ate there every year on my dad's birthday until the place burnt down. Perhaps the victim of over-eager cooking.

My first visit to Delhi was in 1979. That trip was also the time I got to sample one of the delights of north Indian cooking. I was about ten years old; my father was sitting at the table tucking into what looked and smelled like a sumptuous lunch.

"Come here, son." My father beckoned me over. I remember at the time there being smiles exchanged, but hadn't quite registered that they were at my expense.

"Try this." He offered me a spoonful of curry from a dish that lay in front of him.

"What is it, Dad?" I was young; I was hungry. I wasn't refusing to eat it. I just wanted some idea of what I was about to eat.

"Khaa-lai ..." he said, his loving use of Punjabi encouraging me to eat.

"OK." He was my dad. I trusted him.

I guided a spoonful of the diced white substance, smothered in a rich brown sauce, into my mouth. It felt a little strange, but not altogether disgusting. But I distinctly remember registering the experience of a brand-new texture in my mouth.

Everyone started laughing.

"Do you know what it is?" asked my father, fighting back the tears. I shook my head.

"Goat's brain curry," he said. "It'll make you clever!"

"Goat's brain curry," he repeated through tears of laughter. I stood there chewing as they all laughed at the goat-brain-eating fat boy from Glasgow.

"Clever like a goat?" I asked, not previously aware that goats had been particularly celebrated in the animal kingdom for their searing wit and intelligence. This made them laugh even more.

It was at this point in my life that I realized there was something of the accidental entertainer within me.

The only sort of non-Indian fish we had in Glasgow was battered and deep fried. I can only ever remember one occasion when the fish cooked in our house was breaded in the finger form. That was an utter disaster. There are some things that you will have probably realized by now and others that you will shortly learn. I am the way I am about food because:

1. My mum is an amazing cook of Indian food.

2. My dad has a deep desire to experiment and try new things (so long as they don't contain vinegar or tamarind, both of which, in his later years, bring him out in a coughing fit and allergic reaction).

There is no story more indicative of my father's desire to experiment with food and try new things than his doomed adventure into the world of slow cooking. He was evangelical about his kids eating good, freshly cooked food every evening of the week. With both parents working, this presented obvious challenges. That is when my father's discovery of the slow cooker seemed, for a week in the early 1980s at any rate, to revolutionize the world of food in our house.

The slow cooker was the perfect invention for any immigrant family. I remember the first day it arrived. Dad unpacked it and filled it full of pulses and onions and lamb and saffron and prunes. The excitement was palpable. We all saw this selection of raw ingredients enter the terracotta dish of the slow cooker, but we could only imagine the flavours that would result.

As Dad set the machine to cook through the course of the day, he extolled the virtues of the process of gradual cooking, allowing time to pass as the juices from the meat mingled with the sun-sweetened prunes and the deep, earthy saffron, in among which the pulses were plumping and cooking. We left for school, our heads full of fanciful flavours and our hearts brimming with hope.

We returned that evening expecting the house to be permeated with the most exotic of aromas, the table heaving under the weight of Dad's new slow-cooked feast. It would have been a feast indeed, had he remembered to actually turn the thing on.

Fish curry was one of the first Indian dishes I ever learnt to cook. There's no great tradition of seafood in Punjabi households. But what I am about to share with you is a dish born out of economic necessity, a dish behind which is the story of a work ethic and of running a family on a limited budget.

The story of Glenryck mackerel fillets in tomato sauce. Glenryck mackerel fillets in tomato were nothing special. But when my mum made her special masala and then added the fillets, the mackerel was somehow elevated to another place altogether, to a taste nirvana.

For this dish she would slice onions, which was unusual because she almost invariably diced for every other curry. A fine dice allowed the onions to fry away to nothing and form the curry sauce. But, in this case, the slice made a feature of the onions.

She would temper the oil with whole cumin seeds, waiting till they stopped popping in the hot oil; she would then add her other whole spices: cardamom, cinnamon, bay and whole peppercorns. A little turmeric, a pinch of salt and a touch of paprika. A finely chopped chilli joined the pot and then the moment of truth: I would get to open the tin of mackerel.

They would be poured into the pot and once the fish had heated through, dinner was served. Mackerel curry on a bed of white rice. I seem to remember that, by the age of twelve, I was cooking it myself. My mum always told me to experiment, to try more of one spice and less of another and work out how it tasted. If you ever asked her for a recipe, she would be at a loss. She had no idea what she was doing until she was doing it. And every time, it was delicious.

Life has turned full circle; the first curry I learnt to cook was fish in an onion-and-tomato sauce and here I am in Mamallapuram, south India, with a fisherman called Nagamuthu, thousands of miles from Glasgow, decades forward in time, and I am eating fish curry in a onion-and-tomato sauce on a bed of white rice as I watch the Indian Ocean crash against the sun-beaten sands.

Dusk is descending. It is time to prepare dinner. I thought fishcakes would be the thing to do, given the preponderance of fish in the area. I always think of fishcakes as very Scottish.

I get down to peeling and boiling the potatoes. I add mint and coriander. I can't resist chucking a chilli in. When in India ... I chop them up fine with a small onion. Nagamuthu asks me how I would like the seafood prepared. I notice that there are some crabs sitting on the table, looking spare and useless.

They are, in fact, spider crabs: small and delicious but next to impossible to remove the flesh from. The prawns, though, are huge and juicy. And there is also a fish called a coconut fish. The flesh is a cross between mackerel (coincidentally) and grey mullet. It's firm and looks like it should taste good.

I decide that we will have prawn-and-coconut-fish cakes. I'll boil the crabs and they can act as a garnish. Decadent or what?

Nagamuthu's father, Mani, fillets the fish beautifully, effortlessly, instinctively. As he shells the prawns and cracks the crabs I realise that these wizened, tired hands have been filleting, shelling and cracking for over half a century.

He could do it in his sleep. He hands me the prepared seafood. I cut the prawns and fish up into the requisite chunks. I'm sweating so much. It's eight o'clock in the evening and it's still in the 30s. The potatoes are done. I combine the chilli, herbs and onion mixture with the mashed, salted potatoes. I throw the fish in.

I ask Nagamuthu what he uses for breadcrumbs. He produces two bags of sweet rusks, the sort of thing my dad loves to dip in his tea and chew on. I crush a few up and add them to the mixture. He crushes a few more as I start forming the patties. Egg dip followed by the smashed rusks. On to a pan of oil. I throw together a tomato-and-mango salad and, before you know it, Nagamuthu and I are sitting at a table with our fish-and-prawn cakes in front of us.

I think he likes it, because all I can hear is the sea crashing against the beach as he chews on the last crab claw. It occurs to me then that maybe this trip was much less about what I was taking to India and much more about the impact India would have on me.

By travelling to India, I have worked out where home is. I only wish my father was here to dine with me: British me; Indian me; British-Indian me; Indian-British me. Just me.

My name is Hardeep Singh Kohli and I have finally arrived home.

[Courtesy: The Guardian/The Observer. Extracted from Indian Takeaway by Hardeep Singh Kohli, published by Canongate, 2008, £16.99.]

November 16, 2008

Conversation about this article

1: Gurpal Singh (Bilston, U.K.), November 16, 2008, 4:59 PM.

Economics and taste ensured that Hardeep wasn't the only one eating mackerel in tomato sauce curry. As a child, we regularly had mackerel fillets in tomato sauce from the tin, combined with a can of baked beans in tomato sauce (and sometimes chopped pork luncheon meat) in a onion curry base. Cheap at less than one pound to feed a whole family, rich and meaty, a fantastic source of protein and fibre that went down well with roti. We also realise that we weren't the only family in the street to have it. Made by myself many years later at Cardiff University, gora friends, male and female, just went for the pot and completely cleared it out. Eaten very rarely now, I have taught my wife to make it; she now loves it too; best made with some spicy sauce that makes it easy to scoop up and flow down. My mum used to feed on this too, alongside chicken dishes, before taking Amrit a few years ago.

2: Jai Singh (Edmonton, Alberta, Canada), November 18, 2008, 8:26 PM.

Very delectable article indeed. Growing up in the middle class, I can relate to many of the trials and tribulations faced by immigrant families. Aside from the pleasurable read about the power of food, I especially enjoyed reading the bit about identity conflict. Sporting a turban and having unshorn hair can cause other Canadians to easily label me as something else, Punjabi or otherwise. I watched Hardeep's "Hardeep does race", and the part where Hardeep asked random people on the street to pinpoint where he's from, struck a chord with me. A woman in the segment stated that "if a cat goes into a stable and gives birth to kittens, are they horses?" I believed this to be a very weak analogy. First off, as noble as her intentions were, she was comparing cats and horses, two different species of animals; while we are all human beings. Only things different about us are our geographical and cultural difference. Culture itself is quite transparent - meaning you can live within your own, combine cultures, or live with two cultures simultaneously. We're fundamentally the same, its just how we are labeled. Thus it should not matter where we are shipped off to in the world, because we can function just the same.

3: Surrinder Singh (London, England), August 02, 2009, 11:04 AM.

Mackerel/Sardines fillets in tomato 'masala' sauce on a bed of white rice ... it takes me back to my childhood. Still one of my favourite dishes.