Books

Ajit Singh - Best Reads of 2012:

Part I

AJIT SINGH

2012 reinforced my thesis that adventure and stability can indeed cohabitate without offending Heisenberg. At least in my frame of reference, they are not conjugate.

Professionally, I wander off far enough to research new subjects at some depth, yet remain tethered and get pulled back to safety. In these excursions, I rely more on logic and first principles than on experience and convention. This happens frequently enough that I can rely on the pattern. (Notice the paradox?) Personally, my nomadic existence has found an anchor – in India.

While the trips to India are packed with work and are scanty on sleep, they do give me ample life-space to reflect and rejuvenate. This also happens frequently enough that I can rely on the pattern.

2012 was also the year when the direction of “net knowledge exchange” between my kids and I switched; the vector is now pointed away from them. I have received more book recommendations from them than I have given them. They have exposed me to many more unfamiliar subjects than I have done them. Even in the sessions where I am supposed to be coaching them, the nature of their questions and pushback has made me more of a student than a teacher.

All through these exchanges, once again, I have had to rely more on logic and first principles than on experience and convention.

Self-similar patterns at different scales. Life is fractal!

With a few exceptions, the selections in this year’s list are by authors I have not read before (influence of that knowledge-backflow, you see). The categories for this year’s list remain the same as in the past: Literature, Philosophy, Biology, Management/Economics, History/Politics, and Math/Science.

For the first-timers on my annual list, we are at Serial Number 19. My reasons for putting together these reviews have changed quite a bit since 1993. Initially it was merely to share reading recommendations with some close friends. Then, for many years, it was a cathartic exercise – akin to taking stock of the year. More recently, I have discovered that this ritual helps me escape the cacophony of a generally interrupt-driven life.

The act of writing things down – partly from memory and partly by re-reading passages from the books – actually helps me assemble an inner calm.

As in all the previous years, the criterion for including a book in my Top-10 list is very personal: Is this a book that I am likely to read again?

LITERATURE

1 Tatiana de Rosnay, The House I Loved, St. Martin’s Griffin, 2012.

Tatiana de Rosnay was introduced to me in 2010 by a friend who had also recommended the works of Sandor Marai, Andre Brink, and Carolina de Robertis to me in the years before. I had covered Rosnay’s first book, Sarah’s Key in my 2010 review. The story kept perpetually echoing in my head for a long time. I went back and re-read the book this year. The micro stories – most of which I picked up only the second time around – were as telling as the main story itself.

Unlike Sarah’s Key, most of the reviews of The House I Loved were disappointing. In fact some of them were scathingly bad. Yet, I chose to read the book – for three reasons (my inner circle of leg-pullers, I know what you are thinking; and you know who you are).

First, a poignant, deeply disturbing holocaust story such as Sarah’s Key is nearly impossible to outdo. Hence I was willing to

ignore the reviews. Second, the urban redevelopment of Paris (see the timeline in the final pages of the book) was a subject about which I knew nothing, other than the name Haussmann (and that too by virtue of a recent visit to Galeries Lafayette). Third, the prose itself was very uncomplicated and lucid. Here is an excerpt:

“Another very bleak resemblance. The sitting room brings back your mother. The day I met her, but also the day she died. Eight years span those two moments, the happy one and the dreadful one. Yet now, you see, as I write this more than thirty years later, they seem very close in time.”

The book is a work of historical fiction built around the reconstruction of Paris ordered by Napoleon III and implemented by Georges-Eugene Haussmann in the 1860’s. Rose Bazelet, the protagonist of the book resists the orders of demolition of her house. As she awaits the inevitable, Rose writes a series of letters to her deceased husband, Armand. The book tells a conjoined story of their years together and of their relationship with their neighbors, their neighborhood, and the city they both loved. It is also a poignant reminder of the role that material possessions of a shared past play in how we cope with loss and loneliness.

If you are a history buff and would enjoy a concentrated digest on the subject, try David P. Jordan’s paper Haussmann and Haussmannisation: The Legacy for Paris, Journal of French Historical Studies, Volume 27, Number 1, 2004. Or you can turn to the book, Transforming Paris: The Life and Labors of Baron Haussmann by the same author.

2 Herta Müller, The Appointment, Rowohlt Verlag 1997 (English translation – Picador 2002)

My fascination with Romania began only recently, in 2009. I watched movies like The Moromete Family, Michael the Brave, The Miscellaneous Brigade, The Most Beloved of Earthlings, and The Actor and the Savages. I read Lucian Boia’s Romania: Borderland of Europe. And I learnt how to pronounce mi-e dor de tine correctly.

Many of my friends recommended Herta Müller when I lived in Germany. But it wasn’t until her Nobel Prize (also in 2009) that I got interested in her work. I managed to read The Appointment only this past year. It is an exposé on Ceausescu's Romania.

First, an excerpt from her Nobel lecture:

“DO YOU HAVE A HANDKERCHIEF was the question my mother asked me every morning, standing by the gate to our house, before I went out onto the street. I didn't have a handkerchief. And because I didn't, I would go back inside and get one. I never had a handkerchief because I would always wait for her question. The handkerchief was proof that my mother was looking after me in the morning. For the rest of the day I was on my own. The question DO YOU HAVE A HANDKERCHIEF was an indirect display of affection. Anything more direct would have been embarrassing and not something the farmers practiced. Love disguised itself as a question.”

The protagonist of the novel, a factory seamstress, is caught sewing marriage proposals into clothing that was bound for Italy - trying to find an Italian man to help her escape Ceausescu's dictatorship - and is charged with prostitution. The story unfolds as a patchwork of reflections and narrations by the protagonist as she takes a tram ride to her appointment for a questioning session by the Romanian secret police. In the words of The Globe and Mail reviewer,

“Müller's work is political not in any superficial way, but in the more profound sense of literature as bearing witness. Hers is a work where the aesthetic and the political fuse in such a way that one is incomprehensible without the other. Sometimes "telling the truth" can be a distinctly political gesture, and in Müller's work both "telling" and "truth" are so important that, in a way, storytelling is for her, truth-telling.”

Witness Müller's aesthetics and taut prose in the following passages from the book.

“Lately I’m being summoned more and more often: ten sharp on Tuesday, ten sharp on Saturday, on Wednesday, Monday. As if years were a week, I am amazed that winter comes so close on the heels of a late summer”

“It's humiliating, there's no other word for it, when your whole body feels like it's barefoot.”

Whether you are interested in the political history of Eastern Europe or you want to just read a breathtaking story of human resilience, The Appointment is a masterpiece.

3 Alice Ozma, The Reading Promise: My Father and the Books We Shared, Hachette Book Group 2012

This book was a birthday gift – from my older daughter Pavita. Philadelphia Inquirer sums it up the best: “The Reading Promise turns out to be about much more than the love of literature. It is about the love between parent and child, and how a simple act can become enriched with meaning.”

When Alice Ozma was in fourth grade, her father made a promise: to read to her every night, for one-hundred nights. The ritual actually continued until Ozma went to college. A rich memoir of the braided life-courses of Ozma and her father, the book is inspiring and evocative at once.

“I remember that part clearly,” he continues, “… the woman next to us said how sweet it was that I was reading to you. I told her right away that we were on a streak, forty nights in.” We both laugh this time, but I am laughing partly because I know he is wrong. The train was the first night. Obviously. The thing is, no matter how many times we are asked we can never get this story straight. We agree on a few of the details, but I was very young, and he is getting older. Some memories blend together with others.

I have read this passage several times. This is Pavita’s story and mine, with one difference. Pavita’s memory is impeccable – even from the time when she was very young. As for my memory, she and I agree on one fact: I am the ultimate revisionist.

Needless to say, you will most likely resonate with the book if you relate to the character (or role) of Alice or her dad. Alternatively, the sheer range of titles covered in “the streak” is reason enough to read this book. If you fall in this category, don’t be surprised if you feel tempted to revisit and read some of these titles as well; their summaries in The Reading Promise speak as much to grown-ups as they do to children.

PHILOSOPHY

4 Guy Deutscher, Through the Language Glass: Why the World Looks Different in Other Languages, Picador, 2010

Language and Linguistics have been fascinating subjects for me. My first serious interest in the subject came about nearly ten years ago: I attended a lecture by Steven Pinker at the Santa Fe Institute and read Wittgenstein’s Poker in summer of 2003.

I met Guy Deutscher, purely by chance, in July 2006 at the bar at the Old Parsonage in Oxford. Our conversation lasted only about five minutes, but that was enough to get me hooked to his first book, The Unfolding of Language: An Evolutionary Tour of Mankind's Greatest Invention that had been released just a year earlier.

Deutscher’s general area of research is the dichotomy between culture and biology as the basis for language. The Unfolding of Language was a clear testament to his pro-culture “intuitive bias”. In the current book, he further develops his thesis, drawing upon a compelling interplay of culture, history, and perceptual psychology.

Of the vast spectrum of vignettes covered in the book, there are two that intrigue me the most.

First is the issue of linguistic complexity: Does the complexity of a language reflect the culture and the society of its speakers, or is it a universal constant determined by human nature. Deutscher demonstrates through a multitude of observations that many aspects of a language’s grammar are an accurate lens into the culture of its people.

Second, the relationship between language and thought: does linguistic relativity have a logical basis? Do speakers of different languages perceive the world differently? While Deutscher (correctly, in my opinion) rejects linguistic relativity in principle, he suggests color terms, spatial relations and grammatical gender as three areas where a weaker form of language-induced

cognitive bias does hold.

There is one area where I find the book weak: the author’s lack of rigor in making a clear distinction between causality and correlation as the basis for his claims. Correlation between culture and language is evident in Deutscher’s work. Causality is not.

An excellent companion to this book, especially because it explores the issue of causality, is Derek Bickerton’s Adam’s Tongue: How Humans Made Language, How Language Made Humans.

BIOLOGY

5 Ian Tattersal, Masters of the Planet: The Search for Our Human Origins, Palgrave Macmillan, 2012

Ian Tattersal needs no elaborate introduction: he is the Curator Emeritus of the American Museum of Natural History and the author of 10 books on Human evolution. I read his very first book, The Primates of Madagascar during my first year at Columbia (the book was published by Columbia University press a year earlier, and was a required reading for the Ph.D. qualifying exam in Artificial Intelligence).

I also reviewed two of his subsequent books Becoming Human: Evolution and Human Uniqueness in 1998, and The Monkey in the Mirror: Essays on the Science of What Makes Us Human in 2003. Despite the seemingly similar titles, each one of his books is materially original, and breaks new ground.

Masters of the Planet closely follows that trend-line. The first two paragraphs of Chapter 2 on the rise of bipedal apes demonstrate this amply:

“One minor irony of paleoanthropology is that the major components of the human fossil record were discovered in an order exactly inverse to their geological ages. Our recent relatives the Neanderthals initially came to light back in the mid-nineteenth century, when antiquarianism was still the domain of amateurs; the older species Homo Erectus showed up a half century later, as the result of the very first deliberate search for ancient hominids in the tropical zone; and the yet more ancient Australopiths only became decently documented another half century after that, more or less announcing the dawn of the modern age of paleoanthropology. As a result of this history, the Holy Grail of paleoanthropologists has become the extension of the hominid record into the past.

"It is interesting to speculate how differently we might interpret hominid evolutionary history today had the older fossils been discovered first; but while there is no way to know exactly how our views would have been differed in that event, what is beyond doubt is that the order of discovery of our fossil relatives has deeply influenced their interpretation.”

It is easy to extrapolate the central theme of the book: look at the entire body of known evidence and reinterpret it de novo, as opposed to the step-wise incremental-interpretation that we were forced into. Conclusion: We acquired the survival-ensuring biological attributes - when our Homo Sapiens ancestors were competing for existence with several other human species approximately 50 millennia ago – not as a result of a long term evolutionary process, but instead, rather quickly, via an emergent phenomenon. (Hence my classification of this book in the Biology section).

Tattersal draws upon an extremely comprehensive body of evidence from morphology, DNA sequencing, genomics, fundamental chemistry, etc. His approach is didactic yet his prose is very fluid. The bibliography at the end of the book is exactly 15-items long, and is truly the canonical reading list on human evolution.

(Daniel J. Fairbanks’ Evolving: The Human Effect and Why It Matters has far more rigor on the underlying biology and chemistry than Tattersal addresses in his book. An excellent follow-up reading in my opinion).

Continued tomorrow ... Five More Books!

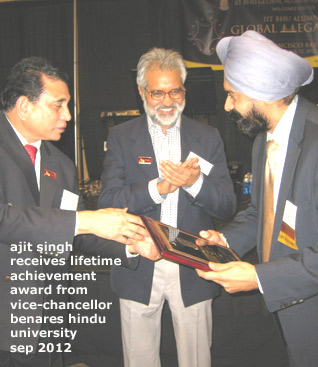

Ajit Singh is currently a General Partner at Artiman Ventures and focuses on early-stage Technology and Life Sciences / Med-Tech investments. On behalf of Artiman, he serves on the Board of Directors of Aditazz, Inc., CardioDx Inc., Click Diagnostics, Inc., CORE Diagnostics Pvt. Ltd., and OncoStem Diagnostics Pvt Ltd. Ajit is also a Consulting Professor in the School of Medicine at Stanford University and is the Lead Director on Board of Directors of Max Healthcare, based in New Delhi.

Prior to joining Artiman, Ajit was the CEO of BioImagene, a Cancer Diagnostics company that was acquired by Roche in 2010. Before BioImagene, Ajit spent nearly twenty years at Siemens in various CEO roles. Between 1988 and 1995, he concurrently served on the faculty at Princeton University. Ajit has a Ph.D. in Computer Science from Columbia University.

December 26, 2012

Conversation about this article

1: Dr Birinder Singh Ahluwalia (Toronto, Ontario, Canada), December 26, 2012, 2:36 PM.

I remember reading a quote once: "Whatever I needed to know about life, I read and learned in grades 1,2 and 3." But reading these reviews, looks like I could use a bit more ...

2: Baldev Singh (Bradford, United Kingdom), December 26, 2012, 11:13 PM.

Wow! That's an impressive bio!