Travel

Montgomery's Ward

T. SHER SINGH

DAILY FIX

Saturday, August 18, 2012

Nubia is the ancient land that spans between Aswan in southern Egypt and the Sudanese capital of Khartoum.

It has an incredibly rich history, though much of it has been misappropriated by those who have had the chance to write it, century after century.

We flew into Aswan from Cairo one late winter morning. As we approached the ground, we could make out short airfields and military installations that pock-marked the vast sands. It was a sober reminder that this remained a troubled region, poised to go to war on a moment’s notice.

It was Tuesday, but not by coincidence. We knew of the weekly camel market held in the Nubian village of Daraw, about 40 kilometres north of Aswan. It began in the early hours of the morning and would, of course, wind down soon after the sun reached its zenith.

The village of Daraw sits at the tail end of Darb al-Arba’in, the Forty Days Road, the old thousand-mile slave-trade route now used by herdsmen to bring camels from the northern expanses of Sudan to a point within easy reach of Egyptian peasants and merchants who fly down from northern population centres to replenish their inventory.

In the airport parking lot, we met up with a jovial Nubian giant who pushed past the crowd of drivers and took us under his wing. We told him the name of our hotel -- the Pullman Cataract, of Agatha Christie fame -- but warned him of a 90-kilometre detour en route, to Daraw and back.

“You vaunth buy a ka-mel?”

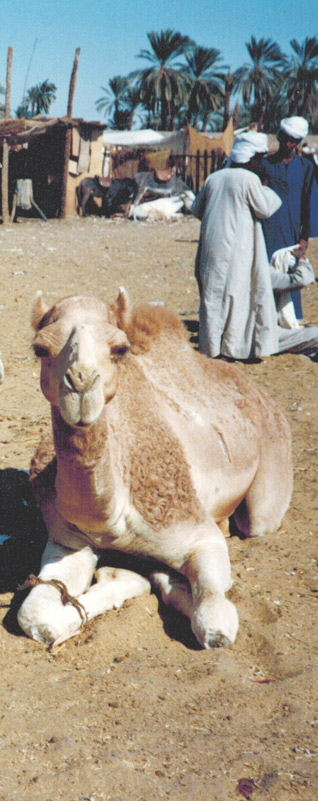

Daraw is an oasis. Date palms everywhere. We honked our way past mud-brick houses, camel caravans, and World War II vintage lorries with camels calmly sitting on their flatbeds, and burst into the clearing of the market itself.

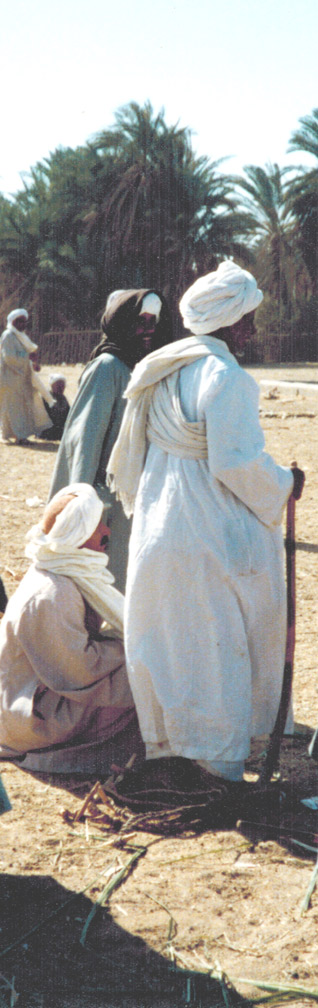

We stepped around people in various formulations: standing, sitting, lying down; alone, or in groups engrossed in the process of deal-making; lounging, waiting for something to happen, a signal maybe, word that it was time to begin the long trek home.

Most of the camels had their left forelegs doubled back at the knee and tied with a rope. The hobbling would have created a hilarious sight -- all these camels playing hopscotch, as if -- but for the fact that it was obviously painful for the sad-looking creatures.

“Why? Why?” my daughter demanded, getting increasingly agitated as we moved from one herd to another. She has a way with animals. The drovers and the merchants observed the scene with amusement and detachment.

Suddenly a voice behind us thundered: “Sa-aa-h!”

We swung around.

An old fellow, in his late 70s, no more than five feet tall, stood taut and erect, his right hand raised in salute. I nodded in puzzlement.

“Good morning, sa-aa-h!” he belted out in pure Cockney, his chest puffed out proudly. “Corporal Saleem reporting, Sa-aa-h!”

And I heard a click. His floor-length abayya hid his feet, but I sensed instantly that he had clicked his heels.

Once we got over the shock, Saleem explained.

He had been an orderly assigned to a soldier named Field Marshal Montgomery during the Second World War. Now a pensioner, he had retired to Daraw, and whiled away his time at the market.

He poured out details of his life during the war. My daughter and I looked at each other a few times; he caught our glances.

He stopped and dug deep into the inside of his white galabiyya and pulled out a plastic pouch. Out came a photo of, well, guess who! Montgomery, looking as dour as usual, complete with scowl, beret and pullover. He stood next to a shorter, younger man, his arms around the latter’s shoulders.

“That’s me, Saah. Just before Alamein, Saah.”

Then, he pulled out his discharge papers and a handwritten note, apparently from the great one himself.

Saleem rattled off, in quick succession, stories of Sikh soldiers he had met while serving Montgomery as his batman. “Fine soljaahs, Saah!” he would exclaim, after each story.

Well, we took Saleem seriously after that.

He insisted on being our guide thereon and explained the hobbling as we began to wander around. It prevented the camels from tearing around the grounds and biting each other - or their human tormentors. Thus, they could graze to their hearts’ content. Each was branded with the owner’s symbol. When they were needed for a trade, a drover could easily retrieve them.

We walked around for a while and Saleem explained to us the fine points of wheeling and dealing in camels.

At one point, we stopped outside a huge tent. It was open on all sides. A number of Nubians were seated on rugs.

In the centre was a man, only his face and hands showing, as black as I had never seen before. He was buried under a swath of turban and what appeared to be at least a dozen metres of factory-white cotton.

“He is the head man of this village,” whispered Saleem. We stared at a spit behind the tent: a huge animal was obviously being prepared for a repast.

We were invited to eat in the sheik’s tent.

We sat down. Shortly, somebody brought around a tray of glasses of tea-coloured liquid, half-filled with quickly disappearing cubes of sugar. I politely sipped from one, while my daughter‘s eyes remained glued on the spit and open fire behind us.

We conversed a bit - the Sheikh and I - in slow-motion: everything back and forth had to go through Saleem, the interpreter. It didn’t take long, we ran out of things to talk about. Or were we merely exhausted by the pace of the exchange?

Saleem and the Sheikh chatted between themselves for a while.

Then, Saleem shuffled across the rug, and snuggled next to me.

“Is she your daughter?” he asked, lowering his voice.

I nodded.

“The Sheikh wants to know,” he whispered directly into my ear, ”How many camels would you want for her?”

I thought I had heard it wrong. I turned around and looked at him. “For marriage,” he nodded solemnly. I had heard the joke a number of times. In Canada, of course. So, I smiled and nodded at Saleem.

But he wasn’t smiling.

He was waiting for an answer.

My daughter had noticed the whispering, and saw me turn quiet. She was curious: “What did he say, Dad?”

“Nothing,” I said.

I turned around and looked Saleem in the eye.

“Will the Sheikh be back here next Tuesday, for next week’s souk?” I asked.

“Yes,” Saleem replied, “he’s always here.”

“Good,” I said, “we have to rush off now to check into our hotel on time. Please thank him for his hospitality. We’ll be back. Next Tuesday. Then …”

I looked at my watch and frowned frantically.

“Let’s go, let’s go, we’re late,” I muttered, nudging my daughter to move. “Really late!”

We walked very slowly, but straight towards our car.

Once inside the car, I hissed at the driver: “God, go, go! To Aswan. Fast. Quickly.”

“What’s the hurry?” my daughter asked.

“It’s way past lunch time,” I answered, truthfully.

Conversation about this article

1: Sangat Singh (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia), August 18, 2012, 3:54 PM.

What a riveting story. You and your daughter have certainly been to places. A perfect travelogue of the same genre as Jan Morris's famous series, if not better.

2: Sunny Grewal (Abbotsford, British Columbia, Canada), August 18, 2012, 8:55 PM.

I wonder how many camels I am worth. Anything less than three would be an insult.