Books

Roll of Honour:

An Interview With Author Amandeep Singh Sandhu,

& Punjabi Translator Daljit Ami

An Interview by PREETI SINGH

Literature based on acts of human atrocities against a race, community or caste has become an independent genre.

For instance, Holocaust literature has influenced, if not defined, nearly every Jewish writer since, from Saul Bellow to Jonathan Foer, and non-Jews like Sebald and Semprun.

On the sub-continent, Partition literature is a big genre too. Memoirs are a large and important part of this genre and they rightly should be.

If the purpose of history is to teach and inform, then literature plays its important role in showcasing sentiment, to reveal and disturb. Memoirs make the events real again, and remind us that people are not statistics and victims must not be forgotten.

While projects like the ‘1984 Living History Project’ are working to collect aural histories of people, ‘Kultar’s Mime’, a poem by Sarbpreet Singh has found expression on the stage.

One of the first books to include the 1984 pogrom was Khushwant Singh’s ‘Delhi : A Novel,’ but it has taken almost two decades and more for literature specific to this event to appear.

‘Helium’ by Canadian Jaspreet Singh was released in 2013 and Meeta Kaur’s anthology ‘My Name is Kaur’ which is sub-titled ‘Sikh American Women Write About Love, Courage and Faith’ is a collection that takes readers down emotional roads, including remembrances of 1984 and Oak Creek.

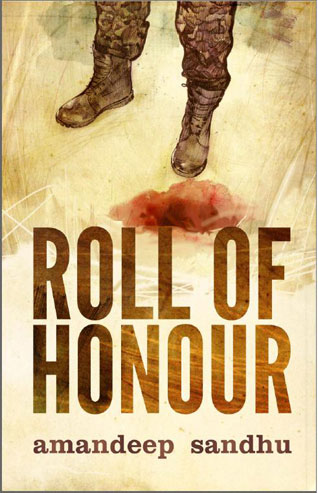

Amandeep Singh Sandhu’s novel, ‘Roll of Honour’, is set in the times of the events of 1984 and follows the journey of its young protagonist Appu. Appu is in military school and just when life is supposed to come together for him, it begins to fall apart. The privileges that he took for granted are no longer his. At school, his class loses its seniority and cannot punish the juniors the way it suffered harassment for six years while in the world outside, the 1984 pogroms against Sikhs and its aftermath are changing the way Appu has viewed his world.

And then comes Balraj, the impressive prefect last year who is on the run and wants to be hidden in the school.

While ‘Roll of Honour’ released in 2012, Amandeep and Daljit Ami (presently a correspondent with BBC Hindi in Punjab & Haryana), collaborated on the translation of the book into Punjabi.

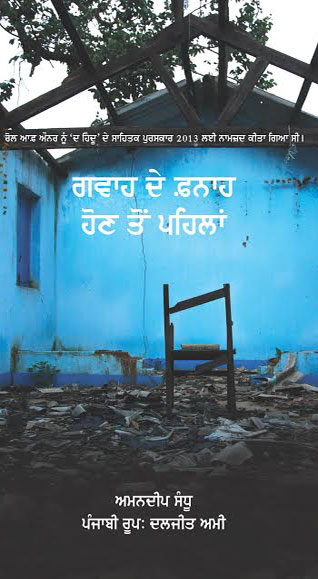

‘Gwah te Fanah Hon To Pehlan’ was released this year, on the 30th anniversary of the pogroms. The English version has received critical acclaim and the translation has opened up a range of dialogue in the community.

Will we see more literature in this genre?

I think so. As the 30th anniversary of the pogrom showed, the wounds still remain fresh in the minds of the Sikh community. While there is forgiveness, there is also a desire to keep the dialogue open so that future generations may be aware of their history.

Presented below are excerpts of an interview with both author and translator.

* * * * *

Q: What was the inspiration for writing ‘Roll of Honour‘?

Amandeep Singh Sandhu [Amandeep]: From the age of seven, growing up in a dysfunctional family and taking solace behind reading comics, I knew someday I wanted to write so I understood what was going on in my life. When I was studying in school, and corporal punishment was rampant, I remember deciding to write about it to understand why the punishment and the hierarchy were in place and how I felt about it.

I kept a diary in those days. The connections between 1984 and the story are obvious. Unlike many others, I had opportunities to leave everything behind, migrate abroad but I knew I wanted to face up to the horrors. The Babri and Godhra incident in each of the intervening decades pushed my desire to explore the violence.

To write the book I did migrate from Bangalore, where I lived, to Delhi, where I could find a job and engage with the horror of 1984.

Q: What made you decide to translate this book?

Daljit Ami [Daljit]: It is a testimonial fiction. Being a contemporary, it was my experience too. With a slight change in specifics it could become my story. It can be a story of any of our contemporaries. Now I feel that this ‘shared experience’ association extends beyond Punjab and 1984.

I always wanted to write about my troubled past but could not dare.

When I met Amandeep Singh, after a bit of interaction on Facebook in 2012 he started a conversation with the first line of ‘Roll of Honour’ without giving any reference of the book.

"A revolver touched his forehead. I got stunned. I had seen Kalashnikov from a hand’s distance."

Then I read ‘Sepia Leaves’ and ‘Roll of Honour‘.

It was my story.

After reading ‘Roll of Honour’ I realized that this is a Punjabi story but there is a space between English and Punjabi. This space was inviting. Punjabi has its own texture and diversity of dialects. I thought that it would give me a chance to do something more then just translation.

This invitation was too big to resist. I thought that it would be a liberating experience, which it turned out to be.

Q: It is interesting how you draw parallels between the events at school and the India outside. Who do you hold culpable for the sodomy, as you call the ‘Operation Bluestar‘?

Amandeep: The Indian state. They let the aspiration of separation grow and then sought to quell it ruthlessly, using force completely out of proportion with the task at hand. The Congress was playing politics with the state and the community that had tirelessly worked to defend and feed the entity called India. There were players among the people too.

Ultimately, it became a fight between forces seeking control and the common people suffered and the community felt slighted and it remains a festering wound on the nation’s consciousness.

Q: What did you think were the main conflicts in the book?

Daljit: The conflict is being played, replayed and negotiated at many levels. Right from identity and sexuality to coming to terms with the past having many layers. For me it is a story of lost innocence overnight. Thereafter it is an endless struggle to comprehend, reconcile and rehabilitate. Every incident makes this process complex and nuanced. The protagonist struggles to comprehend and engages with his fractured self through drugs, music, psychiatric intervention, sexuality and study. Politics and social relations contribute their bit.

Q: In the book you refer to Appu’s confusion regarding his identity because he is a Sikh not following the discipline of the faith? How does one define the identity of a community where many have abandoned the maryada? And what conflicts arise from this?

Amandeep: A clean-shaven Sikh is one part of the confusion. The real confusion is internal: should I lay down my life, or even serve, my community first or my nation. The conflict is not so much in terms of identity but in terms of belonging. Where do I belong: community or nation, when they conflict with each other. A Sikh, as long as he remains a learner, is a Sikh. Yes, external markers of identity, like unshorn hair, do matter but that is not the sum total of the argument.

How does one deal with it? Ask thy own self. Let us as a community also ask ourselves: what about the principle of equality when some amongst us practice casteism?

What about the practice and application of knowledge when many of us have turned to ritual and superstition a la Hinduism? What about the practice of knowledge when some become blind believers?

To me those are important and valid self interrogations.

Q: In what ways would you say the book is different from its English version?

Daljit: It has been written in Punjabi after a gap. Meanwhile lots of things have happened.

The Punjabi version is contemporary, as we have added recent references. Right from the gender debate to recent instances of communal violence have become parts of it. Amandeep used to say, “the straight font is mine and italics is yours.”

Initially I thought that he is trying to be humble. Over a period of time I realized that he has faith in me and wants me to own it. This gave me confidence and we made changes. The first draft was written and read intensely as it was an emotional experience for both of us. Amandeep was reading it in Punjabi and I was revisiting my experience through this transition of ‘Roll of Honour’ to ‘Gwah De Fanah Hon Toh Pehlan’.

Then I read it aloud and we worked on the second draft. It was fun working with him. We made changes, edited and redrafted sentences. We changed its tone, tenor and diction to suit Punjabi. ‘Roll of Honour’ had lots of references from English literature. ‘Gwah ..’ has lots of references from Punjabi literature and folklore.

Q: Were there any difficulties in translation?

Daljit: Punjabi doesn’t have terms for homosexuality, gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender. We have worked out terms. Non-standardization of Punjabi fonts and non-professional Punjabi publishing industry has made Titivillus (the patron demon of scribes) very strong.

Q: Thirty years on, there is no closure on the 1984 Genocide. Who do you hold accountable for the non-closure?

Amandeep: There are a number of those who are accountable: the political forces, the divisions within our own community, the selfishness of those with vested interests, yet the most important is us, each one of us. Have we asked ourselves: what have we learnt from the pogroms? How am I going to use that knowledge to create a better world, not practice those dark deeds? To begin with, they were certainly not ‘riots‘. They were a Pogrom.

Q: When people talk to you about the book, what has made the most impact on them?

Amandeep: The big response has been that there is now a story on the year 1984. The book is the first memoir/fiction on what was happening in those times and how the events impacted young minds. Each of us has a 1984 story. Where were we when the news of Operation Blue Star came? Where were we when the news of Indira Gandhi’s assassination came? What happened to our loved ones? Did something bad happen to any of us? To relatives, friends, and so on.

Yet, it was strange that there was no memoir/fiction around the subject for a long time. I feel this is just the beginning of testimonial fiction in our region. There will be more to come.

Q: If there is anything you would change about the book, what would it be?

Amandeep: As of now what I wanted to change has been captured in the Punjabi translation. Yes, the English book stands by itself and has reached far and wide. I am humbled and thankful for that. Yet, the Punjabi story went home through Daljit and we made those nuanced changes that lent a certain rootedness and contemporary-ness to the book.

[Preeti Singh is the author of ‘Unravel’ and ‘Great Books for Children.’ She manages the book review and author interview website ‘thegoodbookcorner.com’ and her articles have appeared in Mid-Day, DNA, India Abroad, talkingcranes.com and The Scarsdale Inquirer. She is currently based in Scarsdale, New York, USA.]

December 15, 2014

Conversation about this article

1: Kaala Singh (Punjab), December 15, 2014, 1:31 PM.

The author corroborates what I have said in my previous posts: the Congress who treated India as their personal fiefdom was losing power in India as demonstrated by the emergency imposed by Indira Gandhi when she lost the elections. The Congress wanted to manufacture an issue which would help it stay in power. They first planted elements in the Sikh leadership who would make a legitimate struggle for political and economic rights look like a violent separatist movement and allowed it to grow. The Indian State would then build up the separatist hysteria using state controlled media to convince the Hindu majority that Sikhs were a threat and that they needed the Hindu support to eliminate this threat. The "planted" elements in the Sikh leadership were to give the Indian State an excuse to launch a massive attack on all aspects of Sikh life and that is what happened. Many in the Sikh leadership were aware of what was coming and they escaped unscathed. That the lives of the common Sikhs were sacrificed in this game is an unpardonable crime. We have discussed thread-bare the role of the Congress and the Indian State, it is now time to research the role of the Sikh 'leaders' of those times. That Bhindranwale, for example, was in communication with Indira Gandhi and the Home Minster of India, Zail Singh, before Blue Star happened, is beyond doubt. What were his subsequent interactions with the Indian State?

2: Karamjit Virk (USA), December 16, 2014, 9:27 PM.

I don't think the word "enjoyed" reading this book would be applicable. Wasn't sure what to expect and there were certain parts that were difficult to read. However, there was such honesty in this work that I was challenged at times to revisit where I stood on some issues. Amandeep Singh's writing style has a certain visual flow. Look forward to reading 'Sepia Leaves,' though I feel like I have to brace myself before I do so.

3: Swarnjit Mehta (India), December 18, 2014, 11:50 AM.

Very good interview. Questions answered candidly. Hope to read the book in original and its translation in Punjabi. Congratulations to both Amandeep and Daljit.

4: Ajay Singh (Rockville, Maryland, USA), December 18, 2014, 1:27 PM.

Answer to question #2 -- "They let the aspiration of separation grow and then sought to quell it ruthlessly, using force completely out of proportion with the task at hand." This is completely not true. Bluestar was to flush "alleged" militants, not separatists ... and from 37 gurdwaras, not only Harmandar Sahib. None of the "alleged" militants in the Darbar Sahib were charged for any crime, they were charged with "sedition" AFTER the operation was over. The operation was done without the President of the country knowing about it: totally unconstitutional! This was planned MURDER by a state, there is not an iota of justification for Bluestar.

5: Kaala Singh (Punjab), December 18, 2014, 11:03 PM.

@4: And this President who happened to be a Sikh continued to enjoy the luxuries of his position. Leave alone resigning, he did not even react! Could it so happen that this President being the main adviser to the Govt on Punjab affairs while being the Home Minister (before he became President), lost all leverage with the powers when the situation went out of hand ... or was he hand in glove with the Indian state to murder his own people? Whatever the case may be, he was unworthy of any position he held during his career. Like Indira Gandhi, he too held a grudge against the Sikhs for losing power.