Film/Stage

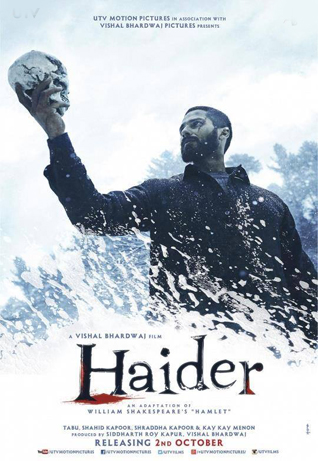

The Film "Haider" Deftly Portrays Kashmir as A Shakespearean Tragedy

VAIBHAV VATS

The director has made his name by adapting into film, using the plays to reflect the violence and vicissitudes of modern India.

“Maqbool,” an adaptation of “Macbeth,” was set in the Mumbai underworld; “Omkara” transported to the feudal badlands of northern India. His latest effort, a loose adaptation of “Hamlet” called “Haider,” which takes place in Kashmir during the turbulent 1990s, has become the most acclaimed and contentious Indian movie of the year.

The film, which opened internationally on October 2, drew a fierce reaction on social media from Hindu fundamentalists, who called for a boycott. Kashmir, a disputed territory claimed by both India and Pakistan, remains a sensitive subject on the Indian subcontinent.

One post said on Twitter: “Any movie that sympathizes with terrorists, glorifies them; insults Indian Army & justifies ethnic cleansing, goes to the bin. #BoycottHaider.”

The campaign’s Facebook page includes a photo of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, a conservative whose election this year has emboldened Indians who advocate a muscular, unapologetic extremism.

Journalists in India’s national media, however, greeted the movie with rapturous praise. The columnist Mukul Kesavan, writing in The Telegraph newspaper in Kolkata, said its “great achievement is to bring Kashmir out of the closet.” The Mint newspaper called it an “immensely effective reimagination of Shakespeare.”

In The New York Times, Rachel Saltz suggested that the movie “grafts its source story less convincingly to its setting” than Mr. Bhardwaj’s previous efforts while providing “the occasional sharp reminder of how cinematically he can construct Shakespearean moments.” Over the weekend, won the people’s choice award in the world genre category at the Rome Film Festival.

The movie’s portrait of Kashmir is radical by Indian standards. Avoiding nationalist arguments, the film portrays the tragic human cost of the conflict and its netherworld of disappearances, military torture and extrajudicial killings.

“When we saw the final edit, we prayed the movie would make it through the censor,” said the journalist Basharat Peer, who helped write the script. Censors cleared “Haider” after 41 cuts. (Mr. Bhardwaj says he made 35 of those cuts “voluntarily,” for narrative purposes.)

Even in the film’s fourth week in theaters, the controversy surrounding it shows little sign of abating. It has been banned in Pakistan, where the censors claimed -- surprisingly, for a movie that casts a negative light on the Indian state -- that “Haider” was “against the ideology of Pakistan.”

The Hindu Front for Justice, a group of fundamentalist lawyers, petitioned India’s Allahabad High Court to seek a ban on screenings of the film, arguing that “Haider” was against the “national interest.” Mr. Bhardwaj and Mr. Peer have until November 15 to reply. The movie is likely to complete its theatrical run in India by mid-November, in any case.

The idea for a Kashmiri originated last year, when Mr. Bhardwaj was seeking a vehicle to complete his trilogy of Shakespearean tragedies. He happened upon “Curfewed Night,” a memoir by Mr. Peer about growing up in Kashmir amid the conflict.“The stories in the book gripped me,” he said. A few weeks later, Mr. Bhardwaj met Mr. Peer in New Delhi, and they began collaborating on the screenplay, drawing on Mr. Bhardwaj’s mastery of Shakespearean adaptations and Mr. Peer’s journalistic realism.

Mr. Peer was an unusual choice for a Bollywood screenwriter. Bollywood movies are for the most part loud, rambunctious affairs, far removed from Mr. Peer’s literary sensibility. Mr. Peer had his reservations, too. “I knew Vishal as an accomplished filmmaker, but I did not know much about his politics,” he said.

Bollywood has not been kind to Kashmir. In the years before conflict erupted in the late 1980s, it served as little more than a tourist backdrop for romantic dance numbers. More recently, it has been portrayed through a purely propaganda prism as a sinister haven seething with terrorists.

Mr. Peer said he felt that “Haider” could chart a new direction. “When I told Vishal the basic premise, he had no problems with it,” he said. “I felt, this is already a big start. Nobody in Mumbai, nobody in the last 25 years in the film industry, had even come close.”

In perhaps the most chilling scene of the movie, a truck full of bodies arrives at a morgue, and a boy jumps from the bloodstained pile, dazed to discover he is still alive. “I was taking material from stories I had reported on and grafting them onto Shakespeare,” Mr. Peer said.

Autobiographical elements seeped into the narrative. Haider’s parents send him to Aligarh, a university town in north India, to shelter him from the violence overtaking Kashmir. The movie’s plot is set in motion when he returns to his homeland to search for his father, who has been abducted by the military.

He is plunged into a looking-glass world where lies and deception are common, and the government has abandoned human rights and the rule of law to crush the armed insurgency.

In a recent interview at a cafe here, Mr. Peer checked his Twitter account repeatedly as dozens of messages poured in, mostly either strong praise or vile insults.

“I’m not apologetic, or scared, or afraid,” he said, noting that he had been denounced or threatened for his journalistic work on several occasions. “I’m proud of a lot of stories and moments in this film. Within the limits of Bollywood, we pushed things as far as we could.”

[Courtesy: The New York Times. Edited for sikhchic.com]

October 29, 2014