Columnists

Is There a Toba Tek Singh in Oregon, USA?

SARBPREET SINGH

THE DIASPORA DIARIES, Volume 6

The Diaspora Diaries is a series of articles that I am writing as I collect oral histories and stories for ‘Lions In The West’, a work of non-fiction that documents the 120-year history of the Sikh experience in America. [Author]

Toba Tek Singh (1955) is the title of a famous short story, written by Sadat Hassan Manto, one of my favorite writers.

The story is set a couple of years after the 1947, when Punjab and the subcontinent was partitioned by the British before they finally went home. The main character in the story is Bishan Singh, a Sikh inmate of a mental asylum in Lahore, who is from the town of 'Toba Tek Singh'. The bitingly satirical story is about the lunacy of Partition and the furious bloodletting that accompanied it.

When the governments of newly carved India and Pakistan decide to exchange some Muslim, Hindu and Sikh inmates of their mental institutions, Bishan Singh is on the point of being shipped off to India under police escort, but upon learning that his hometown 'Toba Tek Singh' is now in Pakistan, he refuses to go.

The story ends with Bishan Singh lying down under the barbed wire that separates the two new countries.

"There, behind barbed wire, was Hindustan. Here, behind the same kind of barbed wire, was Pakistan. In between, on that piece of ground that had no name, lay Toba Tek Singh."

Even though the story is a satire, anyone who has seen mental illness up close and personal cannot help being moved by it. Bishan Singh may try to find repose from the lunacy of Partition by laying down in the no-man’s land between India and Pakistan, but unfortunately there is no such halfway place between the separate worlds of the mentally ill and the ‘sane’ .

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1962) is a novel about mental illness by Ken Kesey, which was nominated by Time Magazine to its list of "100 Best English-language Novels from 1923 to 2005". Set in an Oregon psychiatric hospital, the novel was adapted into an award willing film, directed by Miloš Forman.

It is easily one of the most powerful films I saw growing up and it left a lasting impression in my mind. This capsule review by Lucia Bozzola captures the ethos of the film very effectively:

With an insane asylum standing in for everyday society, Milos Forman's 1975 film adaptation of Ken Kesey's novel is a comically sharp indictment of the Establishment urge to conform. Playing crazy to avoid prison work detail, manic free-spirit Randle P. McMurphy (Jack Nicholson) is sent to the state mental hospital for evaluation.

There he encounters a motley crew of mostly voluntary inmates, including cowed mama's boy Billy (Brad Dourif) and silent Native American Chief Bromden (Will Sampson), presided over by the icy Nurse Ratched (Louise Fletcher).

Ratched and McMurphy recognize that each is the other's worst enemy: an authority figure who equates sanity with correct behavior, and a misfit who is charismatic enough to dismantle the system simply by living as he pleases. McMurphy proceeds to instigate group insurrections large and small, ranging from a restorative basketball game to an unfettered afternoon boat trip and a tragic after-hours party with hookers and booze.

Nurse Ratched, however, has the machinery of power on her side to ensure that McMurphy will not defeat her. Still, McMurphy's message to live free or die is ultimately not lost on one inmate, revealing that escape is still possible even from the most oppressive conditions.

This story however, is neither about Toba Tek Singh; nor is it about Randle McMurphy and his rebellion.

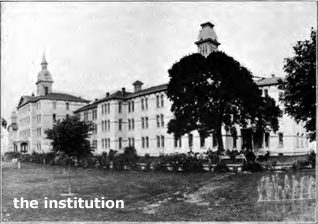

It is about four inmates in a mental institution ("The Institution") in Oregon, who came to an alien land, seeking new, better lives. It is not a story with a happy ending, as for these miserable souls, there was no escape or redemption.

They all left The Institution in the same way. Nothing is known about the circumstances of their arrival but they must have been very different in the case of each individual.

Bur Singh was at The Institution for 24 years and 10 days. He was born in Punjab in 1870. The exact date of his birth is not known. His name was probably not even Bur Singh; when he mumbled his name upon arrival at The Institution to whoever he met in admitting, that’s what his name must have sounded like to ears unfamiliar with Punjabi names.

He was brought to The Institution in early 1929. He probably arrived by train in the dead of night, as did many patients. It is not known why he was admitted. It could have been anything, from ‘brain fever’ to a ‘broken heart’.

The Superintendent of The Institution had complained on record in 1928 that various surrounding counties were committing the elderly, alcoholics, the physically disabled and others who just didn’t ‘belong’ so that they would not have to care for them anymore.

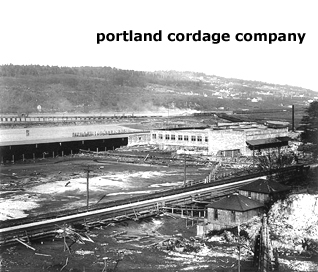

Bur Singh’s profession was listed as ‘cordage maker’. He was a factory worker at The Portland Cordage Company, a prominent hemp rope manufacturer that had been established in 1886. He had been married, but his wife had passed away before him, her name unknown.

He died on February 6, 1953.

Cause of death? Senility.

Chanda Singh, who also went by the name Joe Silver or Silver Joe, was born in Punjab in 1881. He entered the US around 1920, presumably seeking a better life. Not much is known about him. His mother’s name was Mili. He was single when he was brought to The Institution in 1939. His occupation was listed as ‘farmer’ in The Institution’s records, but in all probability he was not a landowner but a poor laborer. His last known address in Portland was ‘Lighthouse Mission’.

There is a church of that name in Portland today but it wasn’t started until the 1950s. The pastor of the church, Dan Wold, indicated that his grandfather had established a mission to serve the needy that was active in Portland in the 1940s. It is likely that Chanda Singh found refuge there, before he was brought to The Institution.

He passed away on June 13, 1941. Friendless and alone, surrounded by strangers in a mental institution. The cause of death was ‘Fibrocaseous Tuberculosis with Cavitation’. This is pure speculation, but it is possible, even likely, that he was institutionalized because he was a single, indigent laborer with a debilitating and contagious illness and nobody to care for him.

Charley Singh was almost certainly not his real name. He had been born in Punjab in 1875. Nothing is known about his family. He hailed from the town of Bridal Veil, on the Columbia River, a logging town created by the Bridal Ceil Falls Lumbering Company. Charley Singh was a laborer and almost certainly worked for the lumber company.

He was brought to The Institution in 1917, where he was an inmate for 33 years and nine months, until his death on December 23, 1950. The cause of death was ‘generalized arteriosclerosis and senility’ with ‘prostatic hypertrophy’. Another significant condition listed as a possible cause of death was ‘psychosis due to alcohol’.

Various accounts of Punjabi men in the Pacific Northwest refer to their rough lives in communal labor camps. Most were single, having left their wives behind in the Punjab and alcohol featured heavily in their lifestyles.

It was commonplace in Oregon for Sikh and other non-white men to receive inordinately harsh punishment and fines for drunk or disorderly conduct. It is possible that Charley Singh was institutionalized because of issues with alcohol and not necessarily because he had mental health issues.

Hazora Singh was the youngest of the four. He was born in Punjab in 1888 to Labh Singh and his wife Harro Singh, as listed on his documents, and was a resident of Linnton, Oregon, another small town on the banks of the Columbia River, now a suburb of Portland.

Linnton then was a company town for the Clark-Wilson and West Oregon Lumber Mills. Hazora Singh was listed as a ‘common laborer’ for the West Oregon Lumber Company.

He was single when he entered The Institution and died on May 9, 1923 of ‘general paresis’ or paralytic dementia, a neuropsychiatric disorder affecting the brain, caused by late stage syphilis. General paresis was originally considered a psychiatric disorder when it was first scientifically identified around the 19th century, as the patient usually developed psychotic symptoms suddenly.

Of all the four, he was the only inmate whose records indicated a condition with clear psychiatric symptoms. It is not known for how long Hazora Singh was institutionalized. The doctor who treated him records that he attended to Hazora Singh between April 24 1923 to May 9 1923; it is possible that his stay at The Institution was a short one.

All four men were cremated. All four were without families or heirs. To this day, their remains lie unclaimed at The Institution.

The legacy of The institution is mixed at best. In an article published in 2004, Michelle Roberts wrote:

Patients sometimes lived four, five or more decades behind the J Building's barred windows, enduring the treatments of the day. In the 1930s, that meant wet-sheet restraints and insulin-induced comas. In the late 1940s and early '50s, surgical lobotomies were done to cut off the emotions of about 150 patients.

At the same time, a crude form of electroshock therapy was used on as many as 50 patients a day.

In 1942, a tragedy at the hospital shocked the nation. A patient, George Nosen, working in the kitchen, mistakenly substituted cockroach poison for powdered milk in the scrambled eggs. Forty-seven patients died; another 400 were sickened.

The hospital's population peaked in 1958, the year the hospital's last lobotomy was performed, with nearly 3,600 patients crowded into identical wards that consisted of tiny, boxlike rooms -- no handles on the doors -- running the length of long, white corridors.

In 2013, Oregon author Diane Goeres-Gardner wrote a book about The Institution. Her account suggests that many people were helped by the treatment they received there:

I was surprised to discover how many people found it to be a haven and a safe place to live and recover. Many of the patients came back to the hospital repeatedly as their mental health issues waxed and waned. For them, it was a refuge from public derision and even violence. Not that they didn’t want to leave and regain the normality of outside life – they did. Often their illness just made that very difficult.

However, she also acknowledges the abuses that occurred there, driven not so much by maliciousness but by the prevalent attitudes to mental illness as well as cultural and social agendas:

(The Institution) was the main state facility for sterilizing thousands of Oregonians whose only crime was being poor, ill, or gay. In essence, it permanently harmed the most defenseless citizens in the state.

The mostly Sikh men who lived in Oregon in the early days of the 20th Century did not leave notable footprints on the pages of history. Their presence had largely been forgotten until Oregon historian Johanna Ogden wrote about the Sikhs of Astoria and other lumber towns on the banks of the Columbia River and the founding of the Ghadar Party in her paper, Ghadar, Historical Silences, and Notions of Belonging: Early 1900s Punjabis of the Columbia River, published in 2012.

Ogden was instrumental in making the City of Astoria aware about the role it had played in the founding of the Ghadar Party, which contributed to the independence of the subcontinent from British colonial rule.

It was during a visit to Astoria in October 2013 during the commemoration of the Centennial of the founding of the Ghadar Party, that I became aware of these four Sikh men who were sent to The Institution and perished there, fading into

an oblivion so deep that they might as well have never even existed.

As I sifted through the few accounts of these Sikh-American pioneers, most notably Johanna Ogden’s, who has become a good friend, I started to find faint traces of the existence of these forgotten men.

Painstakingly sifting through census data, immigration records, prison records and Ghadar Party documents, Johanna Ogden created a map of the Columbia River and documented the names of the Punjabi men who had lived in the lumber company towns in 1910.

It turns out that ‘Bur Singh’ was really Beer Singh, who lived in Portland, was 40 years old in 1910 and was listed as an Operator at the Portland Cordage Company.

The 32-year old Chanda Singh was listed as a resident of the town of Goble, another lumber town on the banks of the Columbia.

‘Hazora Singh’ was in all likelihood Hazara Singh, who is listed on Johanna Ogden’s map as a resident of St. Johns, a town right next to Linnton, the town where ‘Hazora Singh’ was from, according to The Institution’s records.

Of Charley Singh, there is no record.

Hazara Singh died in 1923 and was cremated at the Portland Crematorium. Charley Singh died in 1950.

Chanda Singh died in 1941 and Beer Singh passed away in 1953; both were cremated at The Institution.

For decades, the remains of these anonymous Sikhs who came to America, the land of opportunity, a century ago, pioneers in their own right, have been stored at The Institute, in canisters that are now beginning to fall apart.

Unclaimed.

These were not great men. They did not amass wealth or political power. They did not leave behind families or any kind of legacy, for that matter. But they represent a heroic, forgotten chapter in the Sikh diaspora.

It is a travesty that their remains have languished thus even as Sikhs thrive in America.

The Institution is trying to make amends; the following excerpt is from its website:

While ‘The Institution’ has made enormous strides toward improving the care and treatment of the patients of today, there is unfinished work in honoring patients of previous generations.

‘The Institution’ is custodian of the cremated remains of approximately 3,500 people … who were cremated at this facility between 1914 and the 1970s. These are the cremains that have not yet been claimed.

The hospital hopes to change that and unite the cremains with family members. To that end, the hospital has posted this revised list of individuals whose cremated remains are in its possession. Hospital officials urge anyone who thinks he or she may have a family member who passed away at one of these institutions to review the list. As soon as the connection can be confirmed, the hospital will make arrangements for the cremains to be provided to the family.

Despite The Institution’s best efforts, the remains of Beer Singh, Chanda Singh, Hazara Singh and Charley Singh remain unclaimed. After all, there is nobody to claim them!

Every now and then, a writer who does his utmost to write dispassionately will unearth a story that touches him deeply.

This is one such story.

To me, it is unacceptable that the remains of these men should fester thus. The Gurmat Sangeet Project, a non-profit group that I am affiliated with, has undertaken to claim these remains and dispose of them according to Sikh tradition. An effort to claim the remains has been initiated. Further updates will

follow.

Any of my readers, from Oregon or elsewhere, who have been similarly moved by the story are welcome to get in touch with us to join the effort and support it.

The Gurmat Sangeet Project (www.gurmatsangeetproject.com) can be contacted at sevadars@gurmatsangeetproject.com

Beer Singh, Chanda Singh, Hazara Singh, Charley Singh and all the anonymous men and women whose ghosts haunt The Institution to this day: May they all Rest In Peace.

March 31, 2014

Conversation about this article

1: I. Singh (India), March 31, 2014, 9:23 AM.

I salute you for taken up this project. Thank you.

2: Harman Singh (California, USA), March 31, 2014, 2:57 PM.

Thank you, Sarbpreet, for your efforts at documenting our history.

3: Chintan Singh (San Jose, California, USA), April 01, 2014, 2:43 PM.

Thank you, Sarbpreet Singh ji, for taking on this effort.

4: N Singh (Canada), April 01, 2014, 10:59 PM.

Thank you, Sarbpreet. Men like you give me hope. May Waheguru bless you also.