Columnists

Coming of Age As a Young Sardar:

Part I

SARBPREET SINGH

According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, "Existential angst” is a term that generally connotes a negative feeling arising from the experience of human freedom and responsibility.

Angst is different from fear, in that fear has an object, making it possible for one to take definitive measures to deal with it; in the case of angst, no such "constructive" measures are possible. Angst is often associated with adolescents during their developmental years and is tied to self-perceptions of attractiveness and commonly manifests itself as worry about not being able to find a partner or romantic love.

It is inexorably related to identity and self-image and is amplified by the realization that one has the ability to make choices, which carry consequences.

Surely a mid-life crisis, you ask?

A 50-year old ruminating on existential angst! It would have made for a highly entertaining story, but not quite.

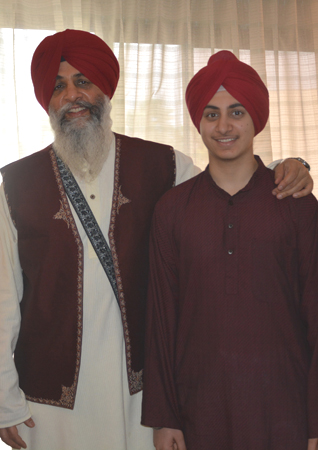

There is however a powerful catalyst for these musings on Sikh identity. Being the father of a sixteen year old keshadhari lad and trying to imagine how the cloak of this identity might sit on the shoulders of a young man growing up in America, is the point of departure for an examination of how my own identity as a Sikh has evolved.

I grew up in Sikkim, in the Eastern Himalayas, where keshadhari Sikhs were as rare as they are in the very homogenous, largely white Boston suburb that my son has grown up in. There was one other Sikh family in Gangtok, with children much younger than my brother and I. Consequently, we were the only two Sikh boys in our school.

Our identity, simply stated, felt like a burden. We stuck out; in our younger years

the plaits on our head were the subject of much derision and when we graduated to joorrahs and patkas, things did not get materially better.

I did have friends. Wonderful friends who stuck up for me and on occasion helped protect me from the inevitable and incessant bullying, but I clearly remember that uneasy sense of never really belonging, that was constantly lurking in the background in my adolescent years.

As much as my identity as a Sikh seemed to be burdensome, shedding it was really never an option. I was very much a ‘goody two shoes‘, growing up; never a rebel and always very cognizant of what was expected of me. As the older son in a family that strongly identified with Sikhi, with a father who I cannot remember having missed his morning reading of the Guru Granth Sahib ever, rebelling against my religious identity was unthinkable.

Besides, we had had one rebellion in the family already and were still reeling from its effects!

My father’s younger brother, who had been educated in elite private schools and colleges, started by the British in the nearby hills of Kurseong and Darjeeling, had already launched a rather spectacular revolt. Raised in boarding schools and rubbing shoulders with the scions of wealthy families, he whole-heartedly embraced the highly westernized cultural mores of his peers. His identity as a young Sikh man who had grown up with no Sikh peers or for that matter anything that reinforced his Sikh identity, was clearly on a collision course with the cultural identity that he had grown into.

When he became enamored of a young woman, the daughter of a prominent, blue-blooded Sikkimese family, who also attended college in Darjeeling, matters came to a head.

One winter, when we returned to Gangtok, we found him without his turban. Apparently a spectacular accident had occurred. He had been lighting a kerosene stove; in those days a common monstrosity in many households, which required air to be pumped into it before it was lit, when it exploded in a fireball, setting his kesh alight! After the ‘accident’ I never saw my Chacha (Uncle - father‘s younger brother) wearing a turban again.

He completed his studies in Darjeeling, tried his hand at a few different things, including teaching at the school I attended, until his young life ended in a tragic train accident during a visit to the Punjab.

Our family had been twice devastated. Once by his repudiation of his identity as a Sikh, which my father who, being much older than him had practically raised him like a son, had tremendous difficulty ever coming to terms with. His untimely death would have been traumatic enough in itself; the fact that it precluded any closure or resolution of the upheaval that his rebellion had caused, probably further amplified the pain that my father and grandfather had suffered.

I was a young child when all this transpired, but the turmoil of these events was inescapable.

Thus I went through my adolescence, more or less resigned to my identity. Notwithstanding the ever-present angst it generated, giving it up was unthinkable.

After graduating from High School in Gangtok, I spent the next four years attending college at Pilani (Rajasthan), far away from my home. My already tenuous connection with my Sikh identity seemed to weaken further as I launched my own quiet rebellion, far away from my parent’s watchful eyes. There were several other Sikhs in the student body and we were after all in Northern India, where Sikhs were to be found everywhere and did not attract the kind of attention they did in Sikkim.

Like most Sikh young men who came of age in the early 80s in India, I was profoundly affected by the events of 1984, in ways that I couldn’t really anticipate when they were happening. During my college years, I was neither interested in acquiring any Sikh moorings; nor did I have the opportunity to do so.

There was really no Sikh community in the area of note and I was content in my circle of friends and happy with my life as a college student, to which my identity was largely irrelevant.

As a young Sikh man, who had grown up far from the Punjab and had never really identified with its culture, I was completely willing to believe everything that I read in the Indian press about what was going on in the Punjab.

It is quite impossible for anyone who did not live through those times to understand the pervasiveness of the Goebbelsian propaganda directed against Sikhs in the mainstream Indian media. All blame for the violence that was occurring at that time in the Punjab was squarely placed upon the Sikh community.

At a personal level, the mitigation in angst that I felt about my identity, which came from leaving Sikkim and moving to Northern India, was strongly offset by the crushing burden that came directly from the accusing finger that was pointed at every Sikh in India.

Quite simply stated, my anxiety at being a Sikh which was driven mostly by a yearning to be accepted, was replaced by pure burning shame. For, after all, was it not Sikhs like me who had embraced lawlessness and violence and were hell-bent on tearing the Indian nation asunder! If every newspaper and newsmagazine said that, it must be true!

Even the 1984 ‘riots’ -- the Orwellian term used by the State-directed propaganda machine for the pogroms -- did not evoke any profound sense of empathy in my mind for the victims at that time. The mostly poor Sikhs of Delhi who had suffered unthinkable horrors did not feel like kin in any way. The carefully crafted news reports in the mainstream Indian press were devastatingly effective in creating a broad sense that the Sikhs had ‘asked for it’.

As a Sikh, in the next couple of years after 1984, it was a chore for me to keep my head held high.

And then in 1987, everything changed.

I left India to attend Graduate School in the US. I was in an alien land that tantalizingly offered innumerable seductions and it seemed to me that my identity had the potential to generate even higher levels of angst, but ironically and unexpectedly, my perception of my identity and its meaning to me underwent a dramatic change.

There were many catalysts.

The mere fact of being able to shut out the Newspeak of India in the mid-1980s was profoundly liberating. All of a sudden the pressure of that pervasive, pointing finger was gone! A few visits to my university library later, I had unearthed many archived articles that provided a very different perspective on the tumultuous events of the last decade in India, 1984 in particular.

I discovered the writings of the intrepid Madhu Kishwar, an Indian journalist and activist and publisher of the progressive magazine, Manushi, who had fearlessly reported on the carnage in Delhi. I managed to find copies of the infamous ‘Black Book’, a report published by Indian Civil Libertarians, which painstakingly documented the role of the ruling Congress party in orchestrating the Delhi massacre.

I stumbled upon another similar report, called “Oppression in Punjab" which for the first time provided an alternate view of what had happened in Amritsar during Operation Bluestar. This view, drawn from eyewitness accounts provided shocking details about the repression that the Indian Government had unleashed upon Sikhs in the Punjab and elsewhere in the country.

Continued tomorrow …

March 24, 2014

Conversation about this article

1: Steve Henshaw (Marlborough, Massachusetts, USA), March 25, 2014, 3:07 AM.

From the picture, I thought I would be reading a proud Papa's Ode To Amandeep. It is after 3 am and I have only half the tale. Sigh ...