Columnists

Is Death Optional?

by RAVINDER SINGH TANEJA

The subject of death may appear a tad morbid. Indeed, it is considered bad form to just talk about death - unless, of course, confronted with the passing of a family member, a relative or a friend. But even then, death presents itself as an unwelcome interruption.

So why am I ruminating over this gloomy subject?

Well, for one thing, it had been on my mind, triggered by the recent passing of a friend's father. In preparing for the eulogy, I turned, quite naturally, to gurbani for guidance. Many of the passages I examined were familiar, but this time around yielded a different perspective.

To compound matters, Ray Kurzweil's book, The Fantastic Voyage: Live Longer to Live Forever, which had been sitting in my pile of unread books, beckoned. Kurzweil suggests that the capability to extend human life indefinitely, and attain physical immortality, is well within grasp.

Reading Kurzweil and reflecting on gurbani's view of death and immortality was a heady mix; not unexpectedly, more questions bubbled up in my head than I could resolve. I suspect that my predicament is not confined to me and might have a broader interest.

What is striking is that death lies at the root of our existential angst. Our fear of physical extinction seems to fuel the fear that drives our lives - consciously or otherwise - to a paradoxical, if not neurotic approach to death and dying.

Although death is imminent, forever around us, we go about our lives as if we are personally immune from it. Death is inexplicable, a perennial riddle, but we never cease to look for an explanation. Despite our efforts, we remain singularly unequipped to deal with its arrival - it always accosts us like an unwelcome and rude intruder.

But above all, what I find most remarkable is our singular and overmastering impulse to defy the certainty of death, to want to stay a step ahead of the Grim Reaper.

The pull of an eternal life has, of course, been tugging at us ever since we were able to contemplate our mortality. This quest has found expression through myth, creation stories, the lives of Himalayan yogis, the "Amrit" of the Sikh Gurus. And in our day, scientists like Kurzweil are holding out the possibility of making death optional.

Whether we know it or not, Immortality is our deepest and most persistent hunger. But is the pursuit of the mystic, the longing for "Amrit" the same as the life extension project of today's scientists? And what are the implications?

The question is worth an examination.

Much of what Kurzweil says appears, like the title of his book, to be fantastic. If this were coming from a less capable voice, one could have dismissed it as science fiction or worse, wild fantasy. Coming from Kurzweil, it seems scarily plausible.

Kurzweil is no crank. He is a respected scientist and a large minded one at that: an award winning inventor and one of today's leading futurists and innovators, he is the winner of the National Medal for Technology and an inductee to the National Inventor Hall of Fame. He is also the author of such acclaimed books as The Age of Spiritual Machines, The Singularity is Here: when Humans Transcend Biology, and most recently, Transcend: Nine Steps to Living Well Forever.

Kurzweil's premise is that by leveraging the intersection of biology, information science and nanotechnology, we can "bridge" our way to living forever. The first bridge in this process involves diet, a heavy supplementation and rejuvenation regimen and exercise - something that Kurzweil practices in his personal life.

To be sure, it is going to take more than just eating your vegetables and exercise to get there.

The second and third "bridges" will involve the merging of our biology with the achievements of genetics, nanotechnology and robotics. The decoding of the human genome will give rise to powerful technologies; combined with rational drugs, tissue re-engineering, and nanobots (mini robots designed to float around in our bloodstream to "fix" any bugs as they arise) it would be possible to re-engineer our genetic code and extend life, potentially forever.

Even if a small fraction of what Kurzweil predicts is realized, it will create a species that is unrecognizable and have consequences that we cannot begin to fathom.

Will it mean the end of life - and death - as we understand it?

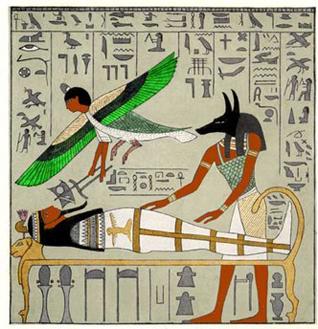

In stark contrast, gurmat challenges our conditioned way of apprehending Reality - which posits a time bound, physical existence that appears solid, concrete and permanent. Gurmat welcomes the termination of physical existence, asserting that we are, in fact, descended from the Immortal Spirit.

Death, in this view, is not the dreadful event that we perceive it to be. Rather, it is a moment pregnant with immense potential, if only we grasp it as the doorway to our Eternal home.

Ironically, what veils this truth and the reality of our authentic essence is God given haumai - the complex structure that gives rise to a sense of self (ego) and its associated mental and emotional framework. The seduction of haumai leads us to identify with, protect and preserve the world of the senses. We become attached to the temporary, and that sets in motion the drama of our daily grind and chase. We lose our orientation.

The Guru provides the necessary insight and discernment into the true nature of things. We are not of the body, with which we have mistakenly identified. We are, instead, part of the Eternal Spirit which is imperishable (abhinashi), riding a degradable, recyclable physical body.

If we recognize and understand that haumai harbours a counterfeit identity, then death is simply like the lifting of a curtain, revealing to the individual what lies beyond: its own Eternal, and Timeless nature.

Gurbani is rich in imagery about death as being the fulfillment of a purpose, of a return home - of returning to the source.

Unlike science and technology, which would have us extend our physical lives, gurmat recommends a shift in our perception. To deprive death, we do not need to avoid it, but greet it instead, by practicing its presence while alive.

What are we to make of the conflicting perspectives of death that gurmat and science offer?

We must be mindful that while both perspectives share a common yearning for immortality, they are rooted in fundamentally different assumptions about the nature of Reality, and consequently offer different prescriptions.

Science is materialistic in that it views matter as the basis of Reality. Avoiding physical dissolution, or pushing out physical death, or life extension, becomes its chief objective.

If, like Kurzweil, we adopt a highly individualized and narrow sense of self and self importance, then clearly death is another conquest to be made and another enemy to be vanquished. Death means extinction.

On the other hand, if we assume gurmat, then death is just a punctuation mark in the eternal journey. It becomes good and desirable, part of the creative and generative process that makes life itself possible. Death means metamorphosis.

Examining these different perspectives has - as you might suspect - raised more questions in my mind than they have solved.

Do we see in science and technology the hubris of all-powerful supremacy? Is the zeal to free us from the grip of physical mortality misguided? What would become of life if we succeeded?

More importantly, are we prepared to live forever? Do we have the psychological and spiritual resources to deal with an existence that lasts forever? Would such a life be a meaningful, purpose driven one? What moral and ethical implications would this have?

Kurzweil's techno-centric view of the world and our species appears to rest on the notion that not only is human capability limitless but that it is actually desirable to reach for physical "immortality."

I am cautious about the unbridled enthusiasm for the omnipotence of science and technology that I see in scientists like Kurzweil.

It is no surprise that I find the gurmat view more alluring.

November 16, 2009

Conversation about this article

1: I.J. Singh (New York, U.S.A.), November 16, 2009, 5:06 PM.

Some intriguing questions: Are we prepared to live forever and secondly the intersection of gene-biology with spiritualism? Yes, we are obsessed with living for ever and many religions rest on this central premise, but not Sikhi. So, death remains our existential angst precisely because it is a veil through which we cannot see. In the biological kingdom, each species has very differing but relatively fixed lifespan. For example, dogs live to about 12 to 15 years, and a rare one may go to 20, but you will not find one living to the ripe old age of 100, as a human can. Finding a 300 year old human would go against all experience. (A mouse is extremely old at a couple of years.) Notwithstanding Kurzweil's brilliance, I am sure gene technology will push the envelope but not to eternity. And then who knows what complications will result from tinkering with the controlling genes. Perhaps with such technology people will live to be several centuries old but not forever. Without death there is no possibility of renewal and rebirth. And that would not be progress, only stagnation - and then death of the whole system. Life to death to life is a cycle bound to time. There is eternity in that - so Sikhi tells me.

2: I.J. Singh (New York, U.S.A.), November 16, 2009, 5:40 PM.

In continuation of my earlier comment I add that the spirit, like water, needs a vessel to give it shape. It has no existence independent of the vessel - just like the mind has no anatomical shape or location of its own.

3: T. Sher Singh (Guelph, Ontario, Canada), November 16, 2009, 6:04 PM.

Jonathan Swift's "Gulliver's Travels" is one of my favourite books because I never fail to learn more from it each time I return to it. Here's something from its summary which may add to this dialogue: "In Luggnagg, Gulliver hears of a race of people called Struldbruggs, who live forever. Gulliver imagines what he would do if he were a Struldbrugg, but when he meets them he realizes that eternal life does not necessarily mean eternal youth. The Struldbruggs actually have both infinite age and infinite infirmity, and they are miserable, senile people." Ergo, we need to think things out a bit before we dream of and strive towards turning our children into a society of Struldbruggs!

4: Panjab Singh (Yuba/Sutter, California, U.S.A.), November 16, 2009, 7:52 PM.

We are alive, therefore we'll die ... Live a purposeful, truthful life and meet death with grace, fearlessness, and ultimate contentment with the realization that you lived a meaningful life that contributed a little to make this world a better place and then pass on the burning torch to your future generations ... it all ends there!

5: Gurdev Singh Bir (Columbus, Ohio, U.S.A.), November 17, 2009, 12:18 AM.

It seems that Man will always have this fanciful desire to rejuvenate and hence strive for an indefinite existence. You rightfully mention that this is all a manifestation of our hypnotic haumai. I personally feel this may be more of a unique yearning in our western world. It probably stems from the fact that in our western world we have extended our average life to the 90+ years and hence the uncomfortable side effects like senility, Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, cancer, etc. that need to be overcome. One only needs to visit a hospice or nursing home and our helplessness and mortality stare us in the face. This fear of the unknown (when a person is nearing death or fear of what happens afterwards) is also a primary motivation towards this race to immortality. Like the Peter Pan story where the child never wants to see the end of it, we are also caught up in this "keep alive forever on this planet" wish. One wonders if any of these scientists ever sit down to think how boring this world would be when you're 300 or maybe 1500 years old? Guru ji reminds us to guard against this 'mithia' that maya has mesmerized us with, this fleeting reality that we are so much in love with. Man stubbornly refuses to acknowledge whose tune we all dance to.

6: Harinder (Bangalore, India), November 17, 2009, 1:10 PM.

All species that have inhabited the earth have departed at some point in time. The Sikh Gurus were blessed by Waheguru and were with Akaal - immortality! A Sikh in my opinion never yearns for death but is a passionate lover of life.

7: Robin (Australia), November 17, 2009, 8:55 PM.

Interesting article. Thank you. Personally, I think that we know deep down we are not meant to die physically, which is why we tend to ignore the idea of death (a healthy reaction, I think). I also think that making death "OK" is a rationalisation of something you think is unavoidable, and comes from the ego - perhaps because people don't understand that they can heal themselves. To me, the basic question is: "Do you want eternal life?" If the answer is "no", then you have a problem with believing you can heal your body, or can find your life purpose, or feel the love you want to feel, or whatever. I don't believe it is "spiritual" to die - I think it is anti-spiritual - we are 3 parts: body, mind and soul, and they are meant to operate together.