People

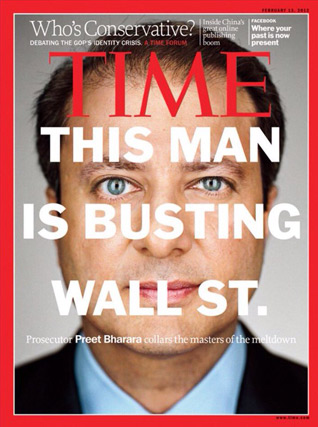

How U.S. Attorney Preet Singh Bharara Struck Fear into Wall Street and Albany

Part II

JEFFREY TOOBIN

PART II

Continued from yesterday …

Preet

Singh Bharara brought cases for insider trading, many based on

investigations that began before his arrival in the office.

One

of Bharara’s predecessors, Michael Garcia, had obtained wiretaps on the

phones of Raj Rajaratnam, a billionaire who founded the hedge fund

Galleon Group. The F.B.I. arrested Rajaratnam, and prosecutors showed

that he used a network of well-placed tipsters, including Rajat Gupta,

the former managing director of the consulting firm McKinsey &

Company, to illicitly gain about seventy-two million dollars through

stock trading for Galleon Group.

There was little ambiguity about

the criminality of Rajaratnam’s intentions. In one tape played at

trial, he called a contact and said, “I heard yesterday from somebody

who’s on the board of Goldman Sachs that they are going to lose two

dollars per share.”

Rajaratnam quickly traded his shares,

avoiding major losses, thanks to this inside information. Convicted in

2011, he was sentenced to eleven years in prison, and given a

ten-million-dollar fine, along with an order to forfeit more than

fifty-three million in gains. (Gupta, who was also a board member at

Goldman, was later convicted of insider trading as well.)

Bharara

followed up with a series of prosecutions of less well-known figures,

whom he nevertheless described as big fish. Announcing the arrest of a

group of mid-level Wall Street brokers, Bharara said, with some

hyperbole, that the case was “precisely the type of pervasive and

pernicious activity that causes average people to think that they would

be better off pulling their money out of Wall Street and stuffing it in a

mattress.” A prosecutor who served in the office at the time told me,

“Preet made promises that he couldn’t deliver. Those cases were not that

big.”

During this period, Bharara did pursue a major target -

Steven Cohen and SAC Capital Advisors - but the investigation ended on

an ambiguous note. Bharara’s prosecutors convicted six lower-level

former employees of SAC Capital, but they never brought a criminal case

against Cohen. Instead, in 2013 Bharara reached a deal with Cohen’s

company, which pleaded guilty to an indictment charging “institutional

practices that encouraged the widespread solicitation and use of illegal

inside information.”

SAC Capital paid a record $1.8-billion

penalty and was effectively shut down. Cohen, however, not only avoided

prosecution but was permitted to continue managing his

multibillion-dollar personal fortune.

“People are always trying

to make these cases mano a mano between me and someone,” Bharara told

me. “But we did the same in this case as we did in any other. We charged

as much as we thought was justified by the evidence.”

There are

some indications that the judges in Bharara’s courthouse resented the

hype underlying his insider-trading offensive. On December 10, 2014, the

Second Circuit Court of Appeals repudiated a key part of Bharara’s

legacy. In some of his major prosecutions, including the Rajaratnam

case, the defendant had traded on information provided by insiders who

were also making money from illegal trades based on inside knowledge.

However,

the cases that Bharara brought against Todd Newman and Anthony

Chiasson, who were stock traders for hedge funds, were different. Newman

and Chiasson were convicted of insider trading based on information

provided by a group of analysts who had obtained it from insiders at

Dell and other companies. As the Second Circuit noted, “Newman and

Chiasson were several steps removed from the corporate insiders and

there was no evidence that either was aware of the source of the inside

information.”

Moreover, there was insufficient evidence that

Newman and Chiasson knew that the insiders had benefitted in any way by

supplying the inside information. In the light of the attenuated

connection between the defendants and the source of the inside

information, the appeals court said, their convictions could not stand.

Between

the lines, the three judges’ opinion betrayed considerable distaste for

Bharara’s aggressive tactics. It referred to the “doctrinal novelty of .

. . recent insider trading prosecutions,” and suggested that Bharara’s

lawyers had attempted to place their insider-trading cases with a

sympathetic trial judge in the Southern District - of judge-shopping, in

other words.

The court said that Bharara was trying, in effect,

to act like a legislator, by rewriting the criminal laws to his liking.

As the court noted, “Although the Government might like the law to be

different, nothing in the law requires a symmetry of information in the

nation’s securities markets.”

According to the judges, there was

always going to be inside information circulating in the markets. But

criminal behavior would entail a meeting of corrupt minds - a tipster

and a trader who both profited from information that they knew was

unlawfully obtained.

Most scholars favor Bharara’s interpretation of the insider-trading laws.

“The

public wants to believe that you can get an advantage from hard work

and research, not because you know a guy who knows a guy,” Samuel Buell,

a professor at Duke Law School, said. Buell is also a former prosecutor

and the author of the forthcoming book “Capital Offenses: Business

Crime and Punishment in America’s Corporate Age.”

It’s hard to

quarrel with Bharara’s observation that “there is some core of material

nonpublic information that is so material and relevant and market-moving

that people shouldn’t be able to take advantage of that over the

average investor, and I think most people agree with that and those are

the kinds of cases that we brought.”

Still, the Newman reversal

led to a cascade of bad news for Bharara. He has had to dismiss twelve

pending insider-trading cases, and defense attorneys are seeking to have

more thrown out as well. (Both Rajaratnam and Gupta are appealing their

convictions.)

Bharara’s targets have even begun to take the

offensive against his office. David Ganek, of Level Global Investors, a

hedge fund that was raided in an insider-trading investigation in 2010,

sued the government for violating his civil rights. In a ruling on March

10th of this year, Judge William H. Pauley III allowed the case to

proceed, writing, “These raids sent shock waves through Wall Street:

investment bankers and traders were indicted, and multibillion-dollar

businesses - including Level Global - were shuttered. But five years

later a different picture has emerged. The Second Circuit rejected the

Government’s theory of insider trading. Criminal convictions were

vacated, and indictments dismissed.”

Bharara plays down his

conflict with Cohen, but he does little to hide his dislike for another

subject of a Southern District investigation: Governor Andrew Cuomo, of

New York. The cause of Bharara’s ire can be identified with some

precision.

In July, 2013, in response to New York’s long history

of corruption in state government (and to some of Bharara’s early

prosecutions of legislators), Cuomo created what was known as the

Moreland Commission. Cuomo’s charge to the commission, which was given

subpoena power, was to investigate corruption in state government, and

to submit recommendations by the end of the following year. Then, on

March 29, 2014, the day that Cuomo announced a budget deal with the

legislature, he abruptly shut down the Moreland investigation.

Bharara pounced.

“Preet

is a very intense guy, and he can get angry,” Rich Zabel, his former

deputy, told me. “It was just obviously outrageous to shut down the

Moreland Commission. We were, like, there is no way that is going to

stand. And we sent the van over.”

A van was dispatched to seize

the commission’s investigative files. Bharara told me, “Our first and

most important goal was to make sure that whatever they had under way

was not lost, and that there was not going to be a whitewash of things

that had been undertaken. If they weren’t going to do it, we were going

to do it.”

Bharara had to show that he could turn the dramatic

gesture into indictments and then into courtroom victories. In addition

to determining whether Cuomo had unlawfully obstructed the

investigators, Bharara had an opportunity to examine the prime source of

corruption in Albany in recent years - the outside activities of state

legislators.

“New York has a part-time legislature,” Blair

Horner, the executive director of the New York Public Interest Research

Group, told me. “That means that most legislators have other jobs. As

long as lawmakers are allowed to serve two masters, the temptation to

misbehave is too great. So what winds up happening, over and over again,

is that they take money in their private jobs to take action as

legislators.”

At the time, the most powerful figure in the

legislature was Sheldon Silver, who had been the Speaker of the Assembly

since 1994. Silver also worked as a lawyer for Weitz & Luxenberg, a

personal-injury law firm in New York City, but he had not fully

disclosed his income or the nature of his duties there. In 2011, the

state had passed a law mandating that legislators disclose outside

employment, and Bharara’s investigators decided to study Silver’s

disclosure forms.

“In the Silver case, we were looking at the flows of money,” Bharara told me.

Silver

had said publicly that he represented “plain, ordinary simple people”

in his law practice, and that his work consisted of spending several

hours a week evaluating possible claims for the firm to accept.

Bharara’s

team subpoenaed Weitz & Luxenberg’s records to see how the firm

accounted for its payments to Silver. The investigators found that over

the previous decade Silver earned a hundred and twenty thousand dollars

annually in base salary, and had received more than three million

dollars in referral fees, all from cases involving plaintiffs’ exposure

to asbestos.

The investigators tracked down the clients. Many

had been treated by Dr. Robert Taub, who ran a clinic at Columbia

University dedicated to research on mesothelioma, a deadly form of

cancer that is linked to exposure to asbestos. Taub, in turn, suggested

that his patients retain Weitz & Luxenberg in connection with any

legal claims they might have. (Asbestos cases can be extremely

lucrative, often generating a million dollars in fees for a plaintiff’s

law firm.)

Prosecutors say that Silver never met with the

patients referred by Dr. Taub, and that he received referral fees based

on their value to the firm.

This arrangement raised the question

of why Taub would refer cases to Weitz & Luxenberg. Taub told

investigators that he began sending patients as prospective clients to

Silver’s firm in the hope that Silver would arrange for the state

government to give financial support to his clinic at Columbia.

Beginning

in 2005, after Taub’s referrals began, Silver used a state health-care

fund that he controlled to send a total of five hundred thousand dollars

to the clinic.

Silver’s disbursements to Taub illustrated his

power as Speaker. As Bharara put it, “He was parcelling out money to

this doctor, Dr. Taub, for his mesothelioma clinic, and nobody had to

agree to it. There was no oversight, and nobody had to know about it,

and his fingerprints didn’t have to be on it.”

The circle was

complete: taxpayer money went to Taub’s clinics, the referrals went to

Weitz & Luxenberg, and the fees went to Silver. (Neither Taub nor

lawyers affiliated with Weitz & Luxenberg were charged.)

Bharara’s

investigators also noticed that Silver used peculiar wording on the

financial-disclosure form. He said that his income came from “Law

Practice (including Weitz & Luxenberg),” suggesting that he might be

receiving income from another law firm as well. “So when we started

looking at payments, because we were looking at the weirdness of Weitz

& Luxenberg, you start looking at bank accounts to see if there were

any other things that were not disclosed,” Bharara told me.

There

was a second firm, called Goldberg & Iryami, a highly specialized

outfit that consisted of just two lawyers. It represented

commercial-property developers who were contesting the assessments used

to determine their tax rates. Bharara’s investigators found that the

firm paid Silver based on fees from two large New York developers,

Glenwood Management and the Witkoff Group, but that Silver did no actual

work for the firm.

Why did the developers set up a scheme to

funnel money to Silver? Both Glenwood and Witkoff had significant

matters before the state legislature - bills that set subsidies and tax

rates that meant millions of dollars to them. In all, Silver made about

seven hundred thousand dollars from the real-estate firms. (Glenwood and

Witkoff were not prosecuted; neither was Goldberg & Iryami.)

Bharara and his team concluded that the money that went through those

companies to Silver amounted to an illegal kickback in return for the

Speaker’s services in the legislature. (Through his lawyer, Silver

declined to comment.)

Silver was arrested on January 22, 2015,

and Bharara - ignoring the traditions of the historically buttoned-down

Southern District - turned the event into a media extravaganza. At a

press conference, he said, “How could Speaker Silver, one of the most

powerful men in all of New York, earn millions of dollars in outside

income without deeply compromising his ability to serve his

constituents? Today, we provide the answer. He didn’t.”

The next

day, Bharara gave a speech at New York Law School in which he mocked the

state’s political leadership, and had some fun with the old adage that

Albany is governed by “three men in a room.” He said, “There are by my

count two hundred and thirteen men and women in the state legislature,

and yet it is common knowledge that only three men essentially wield all

the power - the governor, the Assembly Speaker, and the Senate

president.”

He went on, “Why three men? Can there be a woman? Do

they always have to be white? How small is the room - that they can only

fit three men? Is it three men in a closet? Are there cigars? Can they

have Cuban cigars now? After a while, doesn’t it get a little gamey in

that room?”

Bharara’s splashy announcements may be rooted in

something more than ego. Historically, prosecutors have made their names

in courtrooms, during trials, but in recent years trials have nearly

disappeared. Nearly all federal prosecutions end in plea bargains. Last

year, defendants pleaded guilty in 97.6 per cent of federal criminal

cases; there were 2,002 criminal trials in the federal system, forty per

cent fewer than in 2009. Federal sentencing guidelines virtually

guarantee lower sentences for defendants who plead guilty rather than go

to trial.

“Defense attorneys and their clients just don’t want

to take the risk of going to trial and losing, especially because

federal prosecutors have the time and resources to build strong cases,”

William G. Young, a federal district judge in Massachusetts, who has

studied the decline in trials, said. “We don’t try cases. We process

guilty pleas. And we impose sentences that have been, by and large,

negotiated in advance without our involvement.”

In plea bargains,

prosecutors serve, in essence, as both judge and jury, weighing the

merits of the charges and deciding, within certain ranges, on the

appropriate sentence. But their enhanced power also creates a dilemma

for them. Without trials, how do they tell the public about their work?

For

decades, federal criminal cases have usually begun the same way. A

law-enforcement official, from the F.B.I. or another agency, files an

affidavit (known as a complaint) with a federal magistrate judge stating

that there is probable cause to believe that the defendant has

committed a crime. These complaints, which are drafted by A.U.S.A.s,

have traditionally been dry, bare-bones documents outlining the

defendant’s behavior and the relevant statutes in colorless legal

language.

Bharara’s office, however, has employed what are known

as “speaking complaints,” which, under the guise of showing probable

cause, assume the form of forensic melodramas.

Continued tomorrow ...

Jeffrey Toobin has been a staff writer at The New Yorker since 1993 and the senior legal analyst for CNN since 2002.

[Courtesy: The New Yorker]

May 4, 2016