Columnists

When A Mind Knows No Peace

SARBPREET SINGH

A few days ago, the world was shocked by the suicide of Robin Williams, a much beloved actor and comedian who by all accounts seems to have been a likeable, affable person who wore his celebrity lightly.

The editorials and news reports have been unanimous that the death of this high profile celebrity, who suffered from mental disorders is a ‘teachable moment’.

The following excerpt from an editorial in the San Jose Mercury News makes the point that even in today’s world, there continues to be tremendous social stigma attached to mental illness:

The hardest thing to get across, especially to people who have never experienced anything like depression, is that mental health disorders are physical diseases little different from heart or bone disease except in our lack of understanding of the mind -- and except for the stigma that once was broadly attached to them and even today is common.

Even when we know intellectually that mental illness is a disease, too often we look away. This is especially true when confronted by victims wandering the streets, their odd or incoherent behavior representing a cry for help. But it can also be true of friends and loved ones.

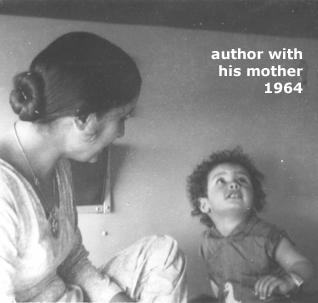

A week ago, I returned from India with my aged parents in tow. Their Kafkaesque journey to the mythical ‘Green Card’, with the interminable quest for decades-old birth and marriage records, was finally over and they were here to live with us.

A couple of days after they arrived, my wife and I were on the horns of a dilemma. We had been invited to a 25th anniversary celebration but we decided that I would stay home with my parents and she would make an appearance at the party on our behalf.

The dilemma had to do with what she would say when our friends, naturally solicitous, would ask after my parents and wonder why we hadn’t brought them to the party. Of course all our friends had met my father when he last visited us in 2007, when he was hale and hearty and extremely sociable, and were very aware of the state that he had been reduced to after his heart attack and stroke.

My mother’s health, however, was another matter. For she suffers from an illness that we have been trying to hide from the world for 50 long years.

And as you have probably guessed by now, dear readers, my mother’s illness is mental and I have spent a lifetime carrying the crushing weight of the stigma that the editorial quoted above addresses.

Well! No more.

My mother grew up in Saharanpur, a town close to the Yamuna river, north-west of Delhi. My grandfather, Sardar Sohan Singh and my grandmother, Sardarni Satwant Kaur were very prominent and highly respected in the Sikh community of Saharanpur. They were both college graduates in an era when education was still the preserve of the privileged.

Both of them were intimately involved with the affairs of the Singh Sabha Gurdwara and the associated Girls’ School.

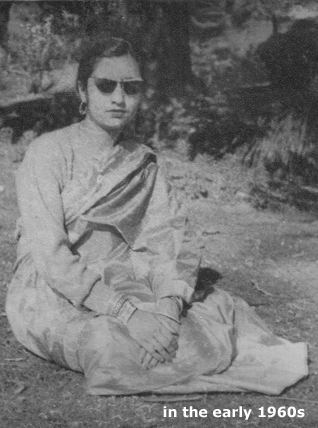

My mother was the oldest of three sisters and by all accounts a celebrated beauty, thoroughly spoiled by numerous aunts and uncles. Gregarious and sociable, she was the darling of the extended Sikh community and would be invited to speak at every major event at the gurdwara and school. Vivacious and carefree, she would mingle freely with everyone and would be constantly surrounded by adoring friends and peers while at school and college.

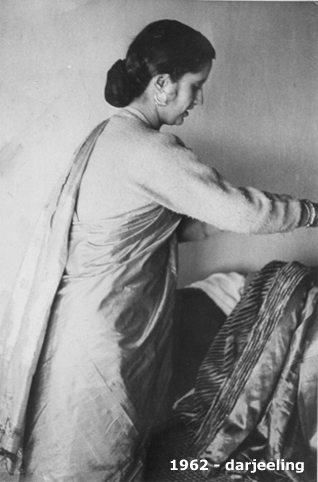

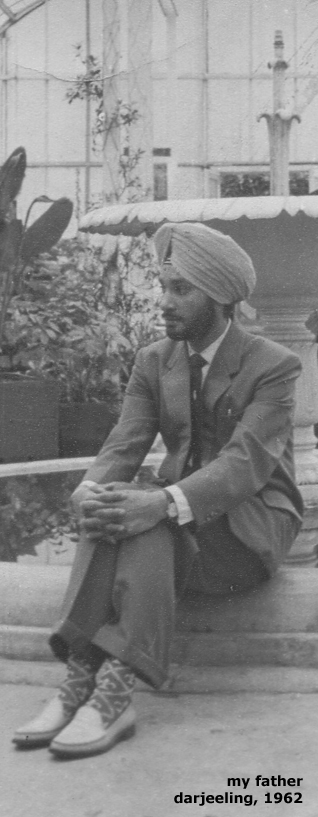

Her wedding, I am told, was quite the event in Saharanpur and her dashing bridegroom who lived in faraway Sikkim and his impressive baraat (bridegroom's entourage and procession) were talked about for years. It felt like a match made in heaven as she left Saharanpur after her wedding to begin a seemingly fairytale existence in an enchanted kingdom in the distant Himalayan mountains.

Within a year, the fairytale turned very dark.

I learned from my mother that during her first pregnancy, this beautiful, carefree and happy young woman inexplicably descended into the shadows of an obsession.

Who knows what caused it. One can only speculate.

Perhaps hormonal changes from the pregnancy altered her brain chemistry or maybe the illness was already within her, lurking in the deep shadows of her mind, looking for an opportunity to explode into her life.

For the remainder of her life, my mother was in the grip of severe OCD (Obsessive Compulsive Disorder). Her mind began to associate pregnancy, childbirth and menstruation with uncleanness and contamination. Anything that an ‘unclean’ person touched, in her mind, would become unclean as well, and washing with plenty of soap and water became her only recourse to keep her mind calm.

As far back as I can remember, my younger brother, who was born three and a half years after me, grew up living with my mother’s disease. It completely dominated her life and every day was a drama involving the surreptitious washing of the unlikeliest of objects. Furniture, walls, floors, electronics, light switches, toys ...

Nothing was exempt. The minute my father and grandfather left the house, my mother would summon our small army of household servants and the surreal opera of her obsession would begin.

As a child I would find it annoying and irritating, particularly if my toys or my precious books found themselves in the path of my mother’s soapy juggernaut.

As I grew older, other emotions kicked in.

Shame and anger, mostly, in equal parts. For on the surface, my mother was very functional. My parents socialized and lived in impossibly beautiful Gangtok; we received a constant stream of houseguests, particularly in the Spring and in the Fall, which are the best seasons for visiting the Eastern Himalayas.

Our houseguests would often include women of childbearing age, a constant cause of stress to my mother. She would hatch elaborate schemes to get their belongings, which had been unclean or contaminated in her mind, washed as well.

As a ten year old, I vividly remember feeling intense shame as I saw these elaborate dramas of deceit unfold as clothes, suitcases and other belongings would magically acquire all kinds of visible dirt, requiring them to be cleaned with soap and water, knowing fully well how these miracles had been wrought. The shame would be accentuated as I watched my mother desperately trying to hide her illness and obsession by constructing breathtakingly complicated stories about how the various belongings of our guests and family acquired the filth that required them to be washed.

As a teenager, I remember my mother’s illness getting worse.

We completely stopped socializing.

Nobody came to dinner anymore. My school buddies, who to this day smack their lips as they recollect the sumptuous treats that my mother’s kitchen used to turn out, stopped getting invitations to our home as I became a desperate accomplice in the plot to hide my mother’s illness from the world.

At some point in time, my shame turned into anger as I started to blame my mother for the stressful and unhappy place that my childhood home had become. My father, who was a pillar-of-the-community kind of person with a strong and dominant personality, was even more profoundly affected by her illness and his helplessness before it. The fights and arguments were hidden from us children, but the tension in the home was palpable. My parents’ relationship and indeed everything else in our lives was completely dominated by her illness, which of course at that time we didn’t even recognize as an illness.

It was a shameful abnormality. The only thing we could do was hide it and pretend to the world that everything was fine.

Later on I learned that my father did make attempts to get her treated. Indian society, as always, has been very cruel to the mentally ill and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder was still unknown to the very thin mental health community in Gangtok and nearby Siliguri, the nearest large city.

I remember an extended visit from my Aunt, my mother’s sister, when I was in High School. It was during this visit that my mother was subjected to whatever psychiatric treatments that were available at the time, including Electric Shock Therapy.

A few years later, after becoming aware of this, I remember watching “One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest”, a film version of Ken Kesey’s novel about mental illness. I vividly remember my gut churning as I watched the main character, Murphy, played by Jack Nicholson, writhing in agony during the electric shock therapy.

Our lives went on.

My mother’s disease continued to dominate her life as I attended college in faraway Pilani (Rajasthan) and then worked for a couple of years in equally distant Bombay, before leaving for the US to attend graduate school.

I had essentially escaped and turned my back on my mother and her illness.

After I left home to go to college at 18, I left the shame and the anger behind as I started to build my own life free from the albatross of my mother’s illness. Of course what I didn’t realize then was that the shame and anger were being replaced by something else that was no less powerful or debilitating.

Yes. I am referring to the guilt that unbeknownst to me, was building deep inside. For after I left home, my interactions with my mother became intermittent and superficial. I would be back home for no more than a week at a stretch. Barely enough time to have polite conversations and enjoy her still fabulous cooking until it was time to go back; her illness, which of course was alive and thriving, conveniently pushed out of the frame of this perfidious snapshot of a congenial homecoming.

A couple of years after I had been in the US, I stumbled upon a book by Judith Rappoport titled ‘The Boy Who Couldn’t Stop Washing’. It was a groundbreaking work published in 1989 which documented the debilitating effects of OCD which, according to the author, afflicted four to six million Americans.

I remember bring stunned upon reading the book. For the first time, I realized that my mother’s behavior was a real illness which could be treated and not just a bizarre and shameful personality trait that needed to hidden from the world.

In her book Dr. Rappoport described behaviors that were scarily familiar to me. The biggest revelation was that it was commonplace for OCD patients to be aware that their behavior was strange and inappropriate and yet be unable to stop them. This had always been the single thing that used to arouse my ire the most. My mother would successfully maintain a façade of normalcy while engaging in what appeared to be egregiously abnormal behavior.

I would gnash my teeth as I wondered why she just wouldn't stop! I remember then feeling a rush of compassion for her and deep shame at my misplaced anger.

One of the revelations in the book was that a new ‘wonder drug’, Anafranil, had been discovered to treat OCD, which had effected near miraculous cures in severely affected patients. The drug was unavailable in India, but my father was able to acquire it from Australia and my mother started taking it.

For a while, it seemed that she too had been miraculously cured!

The story, unfortunately does not end there.

My mother, lulled into a false sense of complacency, stopped taking Anafranil and slowly relapsed into her obsessions again. For the next twenty years, as I focused on building my life and my family thousands of miles away, my mother see-sawed between periods of calm and great agitation, depending on her willingness to take her medication, all the while maintaining the false façade of normalcy before a largely unsuspecting world.

Of course I knew that all was not well, but I didn’t really do anything, caught up as I was in my life and career. Of course this is no excuse in hindsight, but her condition had been our ‘normal’ literally since the day I was born.

Matters took a turn for the worse when my father had a heart attack and stroke in 2009. My barely functioning mother was now saddled with the task of caring for my invalid father, albeit with the help of my brother. It was devastating for her to see the man, who had been her rock her entire life and who had carried the burden of her illness with her, reduced almost to an infantile state. She had always been depressed, a condition that comes with the territory if you have OCD.

The events of the last five years deepened her depression profoundly and led to mutterings about ending it all.

Over the years, when my father and mother had visited us in the US, they made no attempt to hide their utter contempt for life here, particularly for the elderly. They would visit, but they had no intention of ever living here and as a result I never filed their immigration paperwork. What was worse was that after my father fell ill, my own mental state and constant anxiety at being thousands of miles away and worrying about his immediate health issues took center stage, and my parent’s immigration paperwork didn’t get filed for some time.

I visited them in India, but the focus was very much my father and his very obviously deteriorating health. My mother’s illness, that had considerably worsened to the point that she had become almost completely dysfunctional, got pushed to background.

When I arrived in India a few days ago, I found her

in a pitiful state where, in her mind, the entire postal system and banking system in India had been contaminated and any contact with anyone who had ever touched a letter or been to a bank had become the catalyst for increasingly intricate frenzies of ritual cleansing. In the process her physical health suffered; she had lost considerable weight and became a pale shadow of her even her badly broken former self.

She has been here with us for a week and every day, all she wants is the peace which she thinks death will bring her. Completely ruled by her illness, she asked the cab driver who brought us to Delhi from Saharanpur to catch our flight to Boston, if he had ever been to a bank and whether he had children.

In a lapse that I deeply regret, I had omitted to coach the driver and when he told my mother that he often took customers to the bank and that he had a two month old infant, the world seemed to collapse around her. All of a sudden all of our baggage had now been contaminated because of contact with the cab driver and she fretted and wept throughout our journey, mortified that we would be carrying unclean luggage into our home in Boston, which would make it impossible for her to live there in peace.

I know it sounds bizarre to anyone who hasn’t dealt with OCD, but this is the painful reality of the disease.

I don’t know how my mother’s story will end.

There is nothing that I want more than for her to spend her last years on earth in relative peace. Disease free. Liberated from the crushing burden that she has carried for 51 years. For sure there is excellent psychiatric care here and OCD is treatable if not curable in many patients. We have begun the process already.

I do not know if she will be cured or ever know peace. But one thing I do know. I will never hide her illness from the world. If my mother had cancer, it would result in a great outpouring of love and support from everyone around us. Why should it be any different because she suffers from a debilitating mental illness?

Why on earth should we be ashamed? Why should we hide it?

For, trying to hide mental illness is insidiously unfair to the sufferer. Why would we ever want to load up a dear one who is already suffering with the addition burden of guilt and shame?

So what if she has severe OCD? We don’t love her any less for it. In fact we honor her for a lifetime of getting up every day. Making sure that her household is fed. Raising her children. Loving her grandchildren. Taking care of her sick husband. Functioning, when the odds have been against her in every way.

There is heroism in the simple act of surviving.

August 15, 2014

Conversation about this article

1: Bant Singh (New York City, USA), August 15, 2014, 1:43 PM.

Sarbpreet Singh ji, I commend you for opening up to the world a painful chapter in your life's book. I hope others would find the same strength as you. I especially commend your father for not abandoning your mother when her disease surfaced. Wives have been thrown out on the streets in India for lesser reasons by their husbands and in-laws. And many a bride's own parents have refused to accept back a 'tainted' woman, especially one with a mental disease for fear their other unmarried children may not be able to find spouses. This is what our Gurus fought against -- and for social, political and civil rights for ALL, but especially the most needy.

2: Harmohinder Singh Lamba (Johannesburg, South Africa), August 15, 2014, 3:52 PM.

Sarabjit ji, I'm touched by reading your mother's condition. I pray for the better health of your parents. Guru Rakha.

3: P Kaur (New York City, USA), August 15, 2014, 4:03 PM.

Thank you for sharing. We need to acknowledge that we come in all shapes and sizes and this myth of a perfect family (a la Bollywood. e.g.) is just that, a myth. Stories like the one above are liberating.

4: Chintan Singh (San Jose, California, USA), August 15, 2014, 5:21 PM.

I totally agree with comment #1. I can't say enough in praise of your father for supporting his wife and standing by her for 51 years through her condition. My ardaas for both your parents that they can spend their normal life in the company of their children and grandchildren in good health. Best wishes. Thankfully, there are plenty of resources in this country to help patients and support senior citizens.

5: Kulvinder Singh (Melbourne, Australia), August 15, 2014, 8:40 PM.

Dear Sarbpreet-Veer ji-Sat Sri Akaal Thanks for sharing a "hidden" chapter of your life with us. I am always mesmerized by this illness, as my mother also had something similar ... Unfortunately she passed away when I was 18 and I still can't forgive myself for not doing enough seva. Parents are God-sent angels, however, mothers have a better Midas touch when it comes to reprogramming our personalities. May Waheguru give us the strength to take care of our parents in their hour of need, as they did when we were fragile! God bless you and your family. Guru mehar karey!

6: Surjit (Chicago, Illinois, USA), August 15, 2014, 10:19 PM.

Thanks for sharing this wonderful story. Like you, we also pray for her early recovery and salute her endurance to tolerate this problem and still doing all her household chores.

7: Sangat Singh (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia), August 15, 2014, 10:21 PM.

It was in early 60s I was transferred to KMS Estate, Sungei Patani (Kedah) that had a few Sikh families living there. Naturally we got to know them. There was one particular lady who had an obsession to wash the walls of her house daily, especially after the guests had left. At that time it appeared a minor case of craziness. It is only now that Sarbpreet Singh ji's erudite, highly descriptive and most courageous piece has made it clear with recital of the personal experience of his own dear mother what it really was -- OCD. Now I see how a single fly at the dining table had portends of a world war. I also recall a dear friend's mother who had an obsession of hoarding every 'taakki' (a tiny piece of cloth) for future use. Then I remember one of my wife's friend's excessive hand washing trait.

8: Gurmeet Kaur (Atlanta, Georgia, USA), August 15, 2014, 11:47 PM.

Thank you!

9: Parmjit Singh (Canada), August 16, 2014, 1:39 AM.

This should be shared with a wider audience. It is not merely an education in OCD or mental illness. It is an education in humanity that is written by a heart beautifully nurtured by someone.

10: Manbir Singh (Ludhiana, Punjab), August 16, 2014, 3:09 AM.

Thanks, Sarbpreet Singh ji, for this wonderful piece of education for many of us. I am sure this would help many to understand that mental illnesses too are real illnesses. Your describing OCD the way you have done it, would even help a layman to identify the illness before visiting a doctor.

11: Sangat Singh (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia), August 16, 2014, 6:47 PM.

As is my wont, I usually circulate sikhchic.com articles to our core satsang group that meets every Sunday. It is no 'baba' group; Dya Singh ji would willingly be part of it, for example ... he never misses it if he is in town. It is led by Veer Manjeet Singh ji whose study of Guru Granth Sahib is devotedly phenomenal. This is what he wrote in response: Bhai ji. A most gripping piece. But I find no mention of bani. Maybe they did prayers too. But I am certain that no matter what the malady, gurbani can cure you. It is "sarab rogh ka aukhad naam". As Bhagat Bhikhan ji says, if an incurable disease appears which cannot be cured by worldy means, the only cure is naam. "Aisee baydan upaj kharee bha-ee vaa kaa a-ukhad naahee / mathay peer sareer jalan hai karak karyjay maahee." And, finally, "Anay santeh kyho ubaaree raam raa-ay baid banvaaree" - [GGS:659.11] -- "Such is the disease that has afflicted me; there is no medicine to cure it. O my King and Gardener of the world, be my physician ..." Just thinking aloud, I have seen many seemingly impossible cases cured by bani and by Guru's Grace.

12: N Singh (Canada), August 18, 2014, 2:50 AM.

Thank you! My mother suffered from depression and I too grew up under the shadow of her mental illness. No one in our family would acknowledge it and she never got the treatment she deserved. For us it was a dark secret we kept hidden from the world. Thank you again for your heartfelt story and for having the courage to start this dialogue within our community.

13: Amarpreet Singh (Illinois, USA), August 18, 2014, 9:23 PM.

Bravo for sharing! Hopefully, she'll get better with the love and support that she needs, deserves and now has.

14: Reet Kaur (Singapore), August 20, 2014, 11:12 AM.

I feel for you, Sarbpreet ji. My mum had also gone through severe depression. She used to cry so much. The relapses are on and off. Last year, after my pregnancy, a lot changed with me also and suddenly I felt that perhaps I had caught a part of this disease. I wasn't even sure whether it could be a genetic thing or not ... But I always picked myself up and reminded myself that I have to be strong, at least for my mother. And yes, we have nothing to be ashamed of. Thank you for sharing. Praying for your mum.

15: N.S. Gill (Canada), August 20, 2014, 10:18 PM.

It is moving that you have shared the heart-touching story of your dear mother. This is not only educating society but will also help many others in the same situation. Wishing your family good health.