People

The Great Cameraman of Africa:

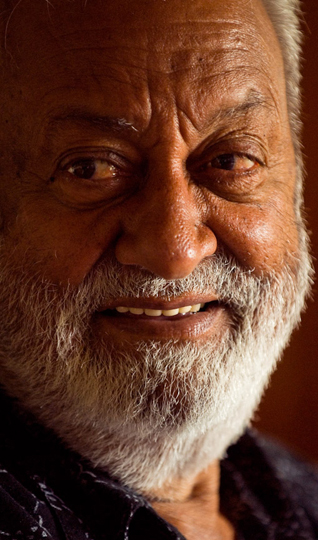

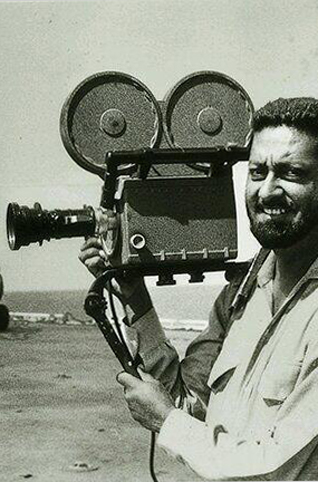

Sir Mohinder Singh Dhillon

Part I

Extracts from Autobiography of Sir MOHINDER SINGH DHILLON

Looking back over the 80 years, I wonder how, as a simple village boy from Punjab who never even finished school, did I end up in Africa, dodging bullets to make a living from shooting hundreds of kilometres of film in some of the world’s most dangerous regions.

I come from a proud martial family of Sikhs. I do not know the exact date of my birth, although my passport says 25 October 1931, Baburpur, Punjab. At the time, births were not registered, and parents habitually exaggerated the ages of their children in order to get them into school early and so have their own hands free during the day.

Baburpur, formerly called Retla (the place of sand), was renamed after Mughal Emperor Babur who had reportedly camped near our village for a few weeks.

MY FATHER, TEK SINGH

My father, Sardar Tek Singh, was the first person in our village to get an education. He was an adventurous man, and in 1918 at the age of 17, he responded with enthusiasm to the recruiting posters for workers on the Uganda Railway in British East Africa.

Believing that there was safety in numbers, he was joined by friends and former classmates from nearby villages and the determined young men collectively took up the challenge of seeking a better life abroad.

This grandiose project of Uganda Railways would change the lives of the tens of thousands of Sikhs and others from the subcontinent who left home for a new life in an unknown land, most of them never to return.

The so-called Lunatic Line laid between 1896 and 1901 from Mombasa into the interior of then-British East Africa to Lake Victoria and subsequently extended into what is now Uganda, opened up the East African hinterland to the outside world. The founding of towns, and their later development into cities, would go on to transform the economies of the region.

When Tek Singh announced his decision to go to East Africa, it upset my grandparents immensely. Their only son was going to ‘darkest Africa’, the prevalent view of Africa at the time (still the perception of many people today).

The money for my father’s first train ticket to Bombay, and for the dhow that would carry him from there to Mombasa, was borrowed from a moneylender in the village at a steep interest rate.

For the young Tek Singh, leaving the village was more than just an adventure. A great deal rested on how he would fare in distant East Africa. Back at home in Punjab, his family would be depending on him for remittances. He also had a young wife to think of. His marriage had taken place six years earlier, when Tek was just 11, and his betrothed, Kartar Kaur, was nine years old.

The railway journey from Babarpur to Bombay took two days and one night. And then it took another two days to find the Uganda Railway’s recruiting agent. His shopping list for the journey – then the cheapest way of crossing the Indian Ocean – included a charcoal stove, two bags of charcoal, all the rations needed for the journey, a sleeping mat, blankets, washing powder, bath soap, tea leaves, and fresh water.

Tek Singh – or Bau ji, as he was fondly called at home – arrived in Mombasa with almost no money in his pockets. He found refuge at a nearby gurdwara, where he slept on the veranda braving the ravenous mosquitoes, exactly like how the thousands freshly arrived on the coast spent their first few nights.

After a week, Bau ji was provided a bachelor accommodation by the Uganda Railways. Later, he and two other young Sikhs shared a small railway house that had the luxury of a tiny garden. The trio of bachelors remained life-long friends.

Bau ji had promptly written home, informing his parents of his safe arrival. The mail though travelled first by sea, and then by rail and horse-drawn carriage and by foot, and took as long as 12 weeks to arrive. By then, his parents had feared the worst.

His betrothed, Kartar Kaur, for her part, was obliged to don widow’s attire (the customary white dress), and was forbidden to use cosmetics. She complied for form’s sake but Kartar refused to believe that her husband was not alive. Amid the uncertainty of my father’s absence, my grandfather Natha Singh lived long enough to hear that his son had indeed reached East Africa safely, but the suspense evidently proved too much for his health. When Bau ji’s letter finally arrived, the family was overjoyed and distributed sweets to everybody, but my grandfather died shortly after that.

Bau ji found himself working for a soon-to-be expanded colonial rail (and shipping) network, one that would come to be known, first as ‘Kenya & Uganda Railways and Harbours‘, and then eventually (in 1948) as the ‘East African Railways and Harbours Corporation‘.

Almost 30 years would elapse before he felt he was ready to bring the rest of his family over to Kenya. Through the 30 years, Bau ji had to be content with getting to see his family during periods of extended overseas leave. He was entitled, once in every five years, a ‘six month home leave’ in Punjab. All but one of the rest of us seven siblings were conceived during successive home-leave visits from our father.

My youngest brother Balbir was born in Kenya. Bau ji was able to save money for the education of all six of his sons, including me. Later, Bau ji sent money to build a primary school in our home village.

Although the India Bau ji had left behind was riven by class divisions, the world to which he now belonged bore even sharper lines of demarcation. The less educated Sikhs, those who were good with their hands, became mechanics, masons and carpenters. Only well-educated Sikhs could expect to land responsible office jobs. Most of the Railway accountants and clerks were Goans, who also ran the catering department. The people from Goa, who had lived under Portuguese rule for more than 500 years, did not mix much with other Indians. They classified themselves as Portuguese. And they already had their own sports club, known as the Railway Goan Institute. There were very few Gujarati-speaking Indians working on the Railway. Some Sikhs left the Railways to venture into business, but it was rare.

Bau ji, for his part, had very little time for any kind of life beyond the Railway. He would walk the 10 km to work from his Railway quarters. He and his two friends Kishen Singh Mangat and Basant Singh Bindra were encouraged by the British Administration to form a Sikh hockey team, so a hockey field and a modest clubhouse were duly built.

It went on to become the Railway Asian Institute Sports Club.

After work, he would walk back home, have his tea, then change into his running-shorts and pick up his hockey stick to hone his hockey playing skills.

OUR LIVES IN BABURPUR

I spent my early childhood in much the same way as my father. We never travelled outside our district in Punjab. There were no road or rail connections nearby. Television was yet to be invented and I did not even know that radios existed.

I first saw a camera when we all travelled to Ludhiana in 1947 to have our passport pictures taken. The camera was one of those contraptions with a black shroud underneath which the photographer’s head would momentarily disappear.

There were no newspapers or magazines from which to learn about the world outside Babarpur. While in India, I had never heard of Mohandas Gandhi. Not until 1948, when I was in Kenya, would I hear about him for the first time – and that was only because he had just been assassinated.

Some of my friends are shocked when I tell them that my main hobby in the village was cock-fighting. I was the proud owner of a champion white cockerel named Raja, or ‘king’. Raja was fed on almonds and garlic, which made him a formidable fighter. We couldn’t afford the luxury of eating almonds. But for Raja, I would settle for nothing less.

Before Raja went into battle, I would fit needle-sharp steel caps over his fighting-spurs – the talons on the inner side of a cock’s leg. In their natural state, a cock’s spurs are sharp enough. But kitted out in steel spikes, Raja could strike deep into an opponent’s belly, killing that poor bird almost instantly.

Talking about this makes me wonder how I could have been so cruel. Back then, however, as a 12-year-old, I got a great kick out of all this. Raja slept next to my bed, I was so proud of him.

My other passion was kite-flying. Together, brother Joginder and I won the championship for both of our last two years in the village.

LEAVING PUNJAB

Things began to change for us in April 1947. The announcement of our impending departure had come in a letter from Bau ji, received in September 1946.

Leaving for Africa just weeks before India and Pakistan were created did at least spare us the carnage of the Partition of Punjab and India. When we left, Punjab and the subcontinent were still a peaceful place. Yet, within just a few months of our departure, some two million Sikhs and other Indians were to lose their lives.

The first time I stepped on to a train was in 1947, at the age of 16, when we were leaving India. It was in the same year that I first travelled by bus. This was a time when, for the first time ever, Indian national election campaigns were canvassing the villages. The year 1947 was thus a significant one in my life. Until then, I had passed my entire childhood without ever having seen either a car or a motorcycle.

I saw a flush toilet for the first time only after we travelled to a nearby town to be immunised against smallpox and to receive our yellow-fever vaccinations.

First, we travelled by ox-cart to Malaudh, the small town nearest to Babarpur where I had been going to school. With Partition looming, electioneering was under way in earnest, new buses were being used to mobilise political support among rural populations.

From Malaudh, we took a bus to Ludhiana. This was only the second bus I had ever travelled in. From there, we boarded the train for Bombay.

In Bombay, we found a cheap hotel, where – in order to cut costs – the whole family shared one large room, with the males in one corner and the women in another. In the floor of the room there were holes through which, peeping down, we could see parts of the room beneath.

Like all Indian travellers in those days, we carried all our own bedding in a sturdy canvas roll, complete with thick leather straps, a leather handle and a special pillow compartment. The bustle of Bombay – the first big city I had ever seen – was overwhelming. On reaching a street, I’d just stand there, transfixed, sometimes for at least three minutes, not daring to cross if there were a car approaching, even from afar. Bombay was simply awe-inspiring.

In India, there were – even then – bribe agents or ‘facilitators’ everywhere to smooth your passage through the formalities of customs and immigration and to find suitable accommodation for you. At the Bombay seaport, a bribe had to be paid for every service that was rendered. We even had to bribe someone in order to establish who else needed to be bribed. Our bribe agent then made sure that we bribed all the right officials.

The ship, named the Khandala, was dirty and worn. Originally a coal carrier, it had been converted to service as a passenger liner. The journey took 14 days. We docked briefly at two ports along the way, Porbunder in Gujarat and Mahe in the Seychelles. Then one day we saw the lighthouse of Mombasa. A tugboat came out to meet us and escorted our ship through a narrow bay into the port. The Africa I arrived in was green and lush. Palm trees swayed in the breeze against a clear blue sky.

What a marked contrast this was to the flat and dusty Punjab we had left behind.

Continued tomorrow … A Wonderous Land!

[Courtesy: The Memory Company. These extracts from Sir Mohinder Singh Dhillon’s Autobiography have been edited for sikhchic.com]

June 8, 2014

Conversation about this article

1: Ari Singh (Burgas, Bulgaria), June 08, 2014, 3:36 PM.

This is one of the best articles I have read in a long time: humorous, realistic, enlightening and nostalgic. I can't wait for the second part. I know Mohinder Singh ji from Nairobi. His best friend, Mangat Singh, was also my best friend. It's been such a long time, he's probably forgotten me (Duli). Then, in Kenya, everyone knows everyone.

2: Sangat Singh (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia), June 08, 2014, 7:51 PM.

What a delightful autobiography to show the indomitable spirit to break away from the pedestrian unity of a village life. Cannot wait for the next installment of this sava-lakh's soaring spirit touching the sky.

3: Himadri Banerjee (Kolkata, Bengal, India), June 08, 2014, 10:26 PM.

Unlike Sikhs' journeys to the Pacific and Atlantic coasts, it offers another gateway to the history of 'Twice Migrants' in East Africa. I do not know when the book would be available in India and in which city and when. I would be grateful to read it. How could I know the name of its publisher or its author's email? Thank you, sikhchic.com for giving the opportunity of reading the first part of it.

4: Hardev Singh Virk (Mohali, Punjab -- Camp, Vancouver, Canada), June 11, 2014, 11:34 PM.

How wonderful to find a man from my neighbourhood writing about his adventurous journey. I know Babarpur and Malaud and started my education at the end of 1947 in Primary School, Lassoi. Hope to read his Autobiography. Thanks, sikhhic.com and T. Sher Singh ji.

5: Louise McLean (London, United Kingdom), September 07, 2016, 1:51 PM.

I worked with Mohinder in Mozambique in 1978. I had set up filming a documentary about Robert Mugabe with Jenny Barraclough for the BBC. Mohinder was a lovely man to work with - a professional in every respect. How lucky we were to be able to use him as our own staff crews weren't keen on filming in Mozambique at that time. Saif awan was his sound man and Sylus Santole his assistant.