Current Events

A Response to "Urban Turban"

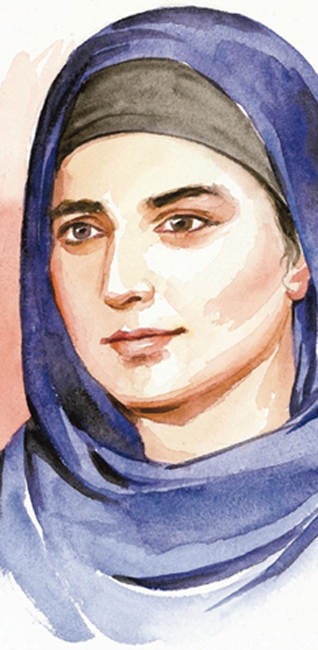

RAVI NAM KAUR

This past year the turban has been discussed in the news more than usual.

Generally any news about turbans helps to educate the public and my initial feelings are always hopeful. Yet, as I read deeper into the articles on the internet and newspapers, I become confused and often angry. Whether it is the banning of head coverings in France, the hearings on the ‘secular’ charter in Quebec or the exploration of Sikh women’s identities, there is unfortunately no shortage of misinformation that leads to my consternation.

This past weekend my husband and I decided to finally put our thoughts to paper and we worked on a response to an especially obvious error in a recent article titled “Urban Turban”.

We began by writing to request an important clarification on the article in the Tribune in Punjab -- where it was first published. (The article was subsequently picked up by sikhchic.com.)

The article was well written -- and edited by sikhchic.com for its own pages -- overall, a sincere effort. We are generally impressed with the high quality of articles on sikhchic.com.

However, we have concerns with both the article and the editor’s preamble appended to the article. We want to provide another perspective on the requirement of wearing a turban.

We are convinced from our own knowledge and our convictions that the turban is neither appropriated from men nor was it in any way less mandatory for Sikh women … until the advent of The Rehat Maryada (Sikh Code of Conduct) in the first half of the 20th century.

Neha Abrahan and Rhea John, the authors of “Urban Turban”, write:

“The answer was found in the distinct look some amritdhari women have adopted in recent decades, by appropriating the dastaar or turban in order to assert themselves as equals within the Sikh milieu.”

I was immediately upset. Sikh women have not appropriated the turban from men, not to make themselves appear equal to men, nor is the practice of Sikh women wearing turbans a recent development.

Appropriation is defined as “the action of taking something for one's own use, typically without the owner's permission.”

I recognize that the intention and tone of the article overall highlights strong women and infers positive attributes to women who wear turbans. It also quotes various women (and the comments sections had several posters who agreed) that the Sikh turban belongs to women as well as men. However, this makes the error about appropriation all the more obvious. Also, as is typical of cursory explorations of women in Sikhi, it makes a muddle of history, anecdote and opinion.

Published writing becomes endowed with authority and if the authors say the turban was appropriated while their interviewees say it is not, the interviewee becomes more of an anecdote, and the writer is elevated to the factual.

Just a few paragraphs after the appropriation statement, the authors themselves discuss the inspiration of Mata Bhag Kaur, a Sikh woman warrior who wore a turban in the early 18th century, at the very beginning of the formation of the Khalsa. It is disingenuous to describe the adoption of the turban or its use as a demonstration of equality as a recent phenomenon while also using the example of a turban wearing woman from 300 years ago. This framing creates a sense that the example of Mata Bhag Kaur was a remarkable exception in history.

Although history notoriously excludes facts about women, there are historical references to not only to Mata Bhag Kaur, but also Mata Sahib Kaur (‘mother of the Khalsa’ and wife of Guru Gobind Singh ji), Rani Sahib Kaur (Queen of Patiala, 18th Century), Rani Raj Kaur (18th century) and many other Sikh women wearing turbans.

Not until 1945 when the SGPC formulated and codified the Rehat Maryada and wrote that it was optional for Sikh women to tie a turban has it become notably less common.

This does not invalidate the original requirement or the prevalence of the practice dating back 300 years. Additionally, even the SGPC refers to the turban as a requirement for all Sikhs without exception when it is politically expedient to do so.

“Every practicing Sikh is enjoined upon to have unshorn hair and have it covered by the turban. It is mandatory for every Sikh and no one has an exemption or option to this [sic] basic Sikh tenets and tradition.” -- Gurcharan Singh Torah writing as President of the SGPC to the President of France

Women have not appropriated the turban because it was always intended for both men and women. Several online sites have highlighted the history (e.g., the Akhand Kirtani Jatha and sikhnet) and others have discussed the experiences of women with dastaars.

I will include just a few examples of the historical writings indicating the turban is a requirement for all Sikhs.

Bhai Daya Singh was one of the first five Sikhs to take Amrit from Guru Gobind Singh. He was the author of a rehatnama which he based on a conversation between himself and Guru Gobind Singh. He describes what he was told when he asked Guru Sahib about the requirements of the Khalsa:

First ensure that each candidate for the Khalsa wears the kacchera, ties the hair in a topknot and covers the same with a dastaar, wears a kirpan in a shoulder strap and stands (in humility) with folded hands.

It is important to note that the term Khalsa is always gender neutral.

Bhai Daya Singh also specifically wrote:

Women should tie their hair in a hairbun and should not keep it loose.

Guru Gobind Singh is quoted by hazoori Sikh scholar Bhai Chaupa Singh (who also served as a guardian of the four sons -- Sahibabad’s -- of Guru Gobind Singh:

A Sikh must observe the requirement of wearing the five Sikh ‘K’ symbols: Kacch, Karra, Kirpan, Kangha and Keski.

The term keski has in modern times been separated into Kes Ki which changes its meaning from Keski -- turban -- to Kes Ki- of the kesh (hair). Many scholars have pointed out that this change is a misreading of the original intent and have innumerable references to support the term keski rather than kesh.

To be honest, some of this was new information for me as I had not distinguished keski from kes ki since I usually read it in English, not Gurmukhi. Because I had already made my decision to wear a turban, I did not know that the Rehat Maryada was so recently adopted and so indeterminate –

“For a Sikh, there is no restriction or requirement as to dress except that he must wear Kachhehra (A drawer type garment fastened by a fitted string round the waist, very often worn as an underwear.) and turban. A Sikh woman may or may not tie turban.” [section 4, chapter x]

Nevertheless, as we quickly found a preponderance of evidence to support the requirement of the dastar for all Sikhs, certainly for Amritdhari Sikhs, and only the Rehat Maryada holding a contrary position, I became more angry and more resigned. Why should I write about this topic? It seems that no matter how many others have made similar and more developed essays on this issue, there are still widely held prejudices.

It was thus even more surprising that sikhchic.com editors added the following:

The dastaar is not mandatory to Sikh women, not even for those who are amritdhari, though greater numbers than before have begun to wear one in recent decades. In fact, majority of the amritdhari women today do not wear the dastaar. Moreover, wearing the dastaar does not add in any manner to the woman’s status; it remains a personal choice.

The statement seems to confirm and support the facts regarding the contemporary appropriation of the turban by women.

To begin with, we don’t know how many amritdhari women today wear the dastaar. We don’t even know how many women are amritdhari. To claim that the majority of amrtidhari women do not wear the dastaar is a common assumption, but it is actually unknown.

Additionally, whether “kesh” or “keski”, why should we relegate or highlight this “K” to a matter of personal choice any more than the other 4 Ks?

The karra is largely accepted so it is uncontroversial. Does this make the karra less of a personal choice and more of a presumed article of faith for all?

Is it only because head coverings are controversial in today’s society that people are scared into polite declarations about personal choice?

We are not so fanatical or fundamentalist to believe that someone is not a Sikh if they do not wear all 5Ks and admittedly we are far from that absolute adherence ourselves. Still, we will not downplay the importance of the dastaar only to preserve the impression of our open mindedness.

I request that we all ask ourselves if our beliefs about the turban are subject to a kind of apology to western ways of thinking. Personally, that figured into my thinking just a few years ago. But I began to question that and I question everything from the SGPC because I believe that the authority on Sikhism is in gurbani, not in a committee.

The misinterpretation of the five K’s as Kesh rather than Keski and the SGPC formulation of a Rehat Maryada and its requirements for Amritdhari Sikhs may be subjects of scholarly discussion. However, it is our opinion that invalidating the long and rich history of turban wearing women erodes the authors’ exploration of women’s identities and women’s equality and feel that the editors comments serve to further misdirect readers.

The dastaar is no longer mandatory to Sikh women according to the SGPC, but according to some writers from Guru Gobind Singh ji’s time, it was not optional.

As well, women’s equality has been asserted in gurbani, not anecdotally and not by committee. We feel that the message being conveyed by the authors of the article as well as the editors, employs a pop-culture version of empowerment that raises women up through acts of defiance as if acts of observance were not sexy enough. The erroneous messages of appropriation of “men’s” symbols are not clever or urbane; they psychologically undermine the very nature of women’s equality in Sikhism.

What drives me to keep reading, to keep researching, and eventually to keep writing is something larger than the turban issue. There is something deeply at work on the psychology and status of women and it plays out as an ongoing battle over the image of women in society.

Currently part of that battle is pitting the western ideology that head coverings are submissive and collusive with oppression against rebellious liberalism where anything goes and the bolder the better. The result is that there is an absence of civil forums to discuss modesty in the public sphere and there is precious little room left to recognize rationality in Eastern practices.

Furthermore, there is almost no understanding of the possibility that one can maintain a critical mind and also find strength in the quiet surrender to the powerful God within us. What I hope for is that we can acknowledge the history of Sikhism’s principle tenets which ask all Sikhs to realize our divinity by wearing a turban and keeping our kesh (hair) and at the same time recognize that it is our choice to avail ourselves of that opportunity.

[The author was born and raised in New England, USA and is a recent immigrant to Ontario, Canada.]

February 7, 2014

Conversation about this article

1: Sarvjit Singh (Massachusetts, USA), February 07, 2014, 9:12 AM.

Ravi Nam ji: Present day Sikhs are mostly male-centric conformists. Most of the Punjabi-origin Sikhs (not Western born), you will notice are also male chauvinists. Many, stuck in the Indian/Hindu mentality, prefer boys over girls, for that matter even mothers wants sons and their eyes light up when they see their sons, but not the same for daughters. A son gets preferential treatment emotionally and in inheritances, etc. This is the sad reality with those who are ignorant amongst us and is like a plague affecting us ... as bad as the Hindu blight of caste. Sikh women need to assert themselves and break the mold. Guru Nanak's first disciple was his sister; Guru Angad's wife was the force behind instituting the Langar and Guru Amardas, who had two daughters, was the true pioneer for women liberation in the sixteenth century by empowering them with leadership roles. These were the Sikh Joans of Arc.

2: MKS (New York City, USA), February 07, 2014, 1:56 PM.

Ravi Kaur ji: An extremely well written and thought out article concerning the turban and its gender based usage. The last 2 paragraphs of the article are very powerful and put into words my thoughts that I could not bring together in a coherent fashion.

3: Bhupinder Singh (New Delhi, India ), February 10, 2014, 4:35 AM.

I wear my turban with pride. However, sometimes I also feel whether we are held up in any way by our appearance, to realize our full potential. Could Preet Bharara, Gulzar, etc., be at a disadvantage if they were turban wearing? Then again, I see some reassuring examples like an endless number of Bank Presidents, Corporate CEOs, a whole slew of law-makers, and of course Waris, and then I am convinced that they excelled by being inspired by the distinct turbaned identity.

4: Harnam Kaur (United Kingdom), February 10, 2014, 7:16 AM.

The only way I would be convinced that the turban is genuinely an impediment to success is if I saw those who discarded it rise to the top by 'being freed of the burden." But what breaks my heart is to see those who have discarded the beautiful Sikh identity and then still struggling with ordinary jobs and mediocre lives. I can see someone being weak and giving up the saroop to win the opportunity to become a Prime Minister, a President, a billionaire, a CEO -- not that I think even that would justfy it! -- but when I see a taxi driver with a Ph.D. and no turban, to take one extreme example, I simply scratch my head and wonder ... [no offence intended to the profession of taxi-driving or any form of honest labour!]