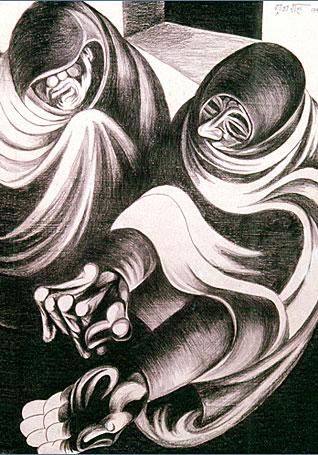

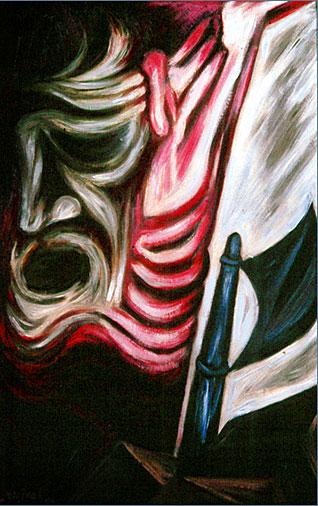

Homepage image: detail from painting by GuruKirin Kaur. Images below: first and second from bottom - details from paintings by Satish Gujral. Third from bottom - detail from painting by Jimmy Engineer.

Columnists

A Sikh Boy

A Book Review by MANJYOT KAUR

A SIKH BOY, by Mohinder Singh. Harper Collins Publishers, New Delhi, 2006. ISBN 81-7223-526-7. 230 pages. Price: Rs. 295.

While fictional, A Sikh Boy is steeped in the realities of the Partition era as personally experienced by its author.

Author Mohinder Singh, a member of the Indian Administrative Service for thirty-five years, retired as Secretary to the Government of India. This is his third book; in addition, over a thousand articles he has written have appeared in India's leading newspapers and magazines.

This work's setting, the idyllic village of Sripur, is based on Mohinder Singh's own birthplace of Haripur, a picturesque mountain town in the North West Frontier Province. Its narrator and main protagonist, sixteen-year-old Monu, can be considered to be an earlier incarnation of the writer himself.

Even before we are introduced to the many members of Monu's Sikh middle-class joint family, or given a glimpse of Sripur's scenic beauty, the plot swings into action. It is December 1946, and one of the Muslim League's Direct Action Days is underway. As Monu tells us, these demonstrations usually end in incidents of violence against Sikhs and Hindus, who own the bulk of the town's businesses. In the month before, we are informed, a local gurdwara was burnt down, its resisting granthi clubbed to death.

On this sunny winter Sunday, Monu's father, Sadhu Singh, the much-revered headmaster of the local all-boys' Sikh High School, as well as his two uncles, are away. Deeming it is up to him to defend the family home, the biggest and best-built edifice of a compact colony within the school premises, as well as its remaining occupants - his mother Jogi, his younger brother and sister, and his grandmother - Monu takes his father's hunting rifle and ascends to the roof "in a fit of bravado".

"Even the thought of firing at someone sends shivers down my spine", he confesses. "I'm someone who has slunk away from every bully-boy. To me, the very idea of hand-to-hand combat is unthinkable".

To his enormous relief, the rioters leave his house unscathed, preferring to loot the school's office instead.

By nightfall, Monu's father returns, and we are treated to the first of the engrossing sections interspersed throughout the book simply entitled "Sadhu's Diary". A man seemingly at the peak of his powers, possessed of a brilliant intelligence and, in the admiring words of his elder son, "unimaginably stylish", it is easy to see why Sadhu is Sripur's most prominent and widely-respected citizen.

Besides delving into his fascinating personal reminiscences and introspections, his diary entries adeptly convey to us his tension and concerns regarding ominous pre-Partition events, to which only a mature viewpoint would be able to give a sense of perspective.

The considerable privilege which naturally results from Monu's status as Sadhu's elder son proves to be, time and time again, a decisive factor in much of the book's action. His is a most enviable existence, sheltered from many of life's brutish aspects, full of undeserved favors and overlooked transgressions. Although an excellent student, his major focus does not seem to be on his studies, but rather on experimenting with his nascent sexuality.

Whether he is matter-of-factly recounting being sodomized at the age of twelve by a male servant, dissecting his fumbling homosexual escapades with classmates at the hostel of his prestigious college, or boasting about his lustful "snatched action" with the family's shapely maid, the astonishingly frank description of these activities is, without any doubt, the book's most surprising aspect.

These explicit scenes, especially those that bring to our attention the exploitative nature of his encounters with the female servant, also serve to make us aware of the negative changes in Monu's personality and mindset that are gradually taking place. Subtle at first, they become increasingly visible as pre-Partition communal violence starts "hotting up".

It is notable that Monu is not the only one whose sexual exploits are revealed. Lest we believe Sadhu's putatively sterling character is an unblemished one, his extramarital affairs (Jogi complains that "he attracts women the way a sleeping man attracts mosquitoes") are also disclosed, although not as graphically. It is evident that both father and son greatly benefit from a firmly-entrenched cultural double standard of acceptable male-female behavior.

As 1947 begins, vignettes of Monu's everyday life - his interactions with his parents and siblings, his scholastic trials and triumphs, the addition of his uncles' wives to his extended family - are adroitly alternated (especially through the medium of Sadhu's insightful diary entries) with scenes of mayhem and portents of the increasing carnage to come.

A schoolboy upon whom Monu had a particularly torrid crush is killed by Muslim looters while trying to help salvage goods from a gutted grocery store. A long-time servant of Monu's family, returning to his ancestral home, is murdered by armed raiders pillaging the area's Sikh and Hindu settlements; his wife and daughter are among the group of womenfolk who escape the brutal fate that awaits them at the hands of the marauders by jumping into the village well.

Growing numbers of Sripur's Sikh and Hindu families start to leave for what they believe might be safer ground. Many members of the Sikh High School's teaching staff are among them, and Jogi is exhorting Sadhu to do likewise. While he had heretofore managed to deflect his wife's wish to evacuate the family to her brother's home in Patiala, Sadhu's resolve finally begins to break down when popular Muslim sentiment becomes so inflamed that the local chief minister's official residence is attacked and the bazaar is burnt to the ground.

Shortly afterwards, a delegation of the town's Muslim gentry pay him a visit and respectfully, but in no uncertain terms, tell him it is no longer safe for him and his family to remain in Sripur: Pakistan is about to come into existence.

As they clamber onto the overloaded truck that will take them away, a humorous moment, albeit an ironic one, is shared:

Jogi was the next one in, dangling her heavy bunch of keys, some thirty of them, big and small. I couldn't help smiling at her taking the keys when the connecting locks were being left behind.

Levity is quickly replaced by heartbreak, however, as bringing along their devoted little terrier proves impossible. As the truck veers off the compound and hurtles down the road, a most pathetic scene comes into view as the dog is spotted frantically, but vainly, running after the vehicle.

Once relocated to Patiala, lodged in the claustrophobic quarters of his brother-in-law's house, Sadhu suffers a heart attack. His delicate condition only worsens when he learns that his brother, who has insisted on returning to Sripur in an attempt to sell the family's land holdings, has been savagely beaten by a Muslim mob and, in order to avoid certain death, has converted to Islam.

Monu, his collegiate activities on hold, loiters on the streets, where he is inexorably sucked into the company of nineteen-year-old Satnam, a Sikh gangleader gripped with one burning resolve: revenge against Muslims. He rationalizes his propensity for extreme violence by claiming he restricts his victims to those who appear to be above the age of ten. Impressed by the older youth's "air of self-assurance and strength, the two qualities I lack the most", Monu meets him every evening at the group's headquarters, a deserted house filled with a cache of swords and makeshift bombs.

A scene in which we are shown the extent of Monu's decline in personal morality soon follows.

One day, while walking with Satnam in a Muslim neighborhood devastated by rioting (and witnessing him cold-bloodedly slashing open the belly of a wounded woman they encounter sprawled in the street), Monu spots a policeman, wearing only the upper half of his uniform, brutally forcing three stark naked women, one of them barely a teenager, into a shed.

Instead of evincing total revulsion, he tells us: "For the first time in my life, I have seen frontal nudity in public and at such close quarters. It arouses me". When Satnam offers to procure the youngest one for his carnal pleasure, he declines, not for reasons of right and wrong, but out of selfish apprehension that she, in anger or desperation, might attempt to injure his genitals.

Monu suddenly realizes "the wheel has come full circle" when he uses his father's gun (the same rifle he had quivered to hold in the opening scene) to fire into a house occupied by Muslim women and children: "Once, I had asked for the gun, weighed under mortal fear. Now, I have fired it, cocooned in the safety net of an assaulting majority. (...) In a majority, you can easily be brave".

The last chapter, entitled "One Year Later", finds Monu in Delhi, enrolled at St. Stephen's College, attempting to forge a new beginning for himself.

His uncle, who has managed to escape Pakistan and rejoin the family, fervently re-embraces Sikhi, seized with "a fierce loyalty for the faith of his birth, which he had never felt before". While his mother does her best to forget the past, his father keeps trying to remember it.

As Monu tells us of Sadhu at book's end:

For him, the scars of this forced separation will never heal. The rehabilitation process is on. Yet the pangs of Partition persist - 'The deep, unutterable woe, which none save exiles feel'.

A Sikh Boy's skillful sense of characterization is its strongest asset. It is indeed compelling to witness Monu's metamorphosis from a happy-go-lucky teenager to a callous youth to a young man hoping to make a fresh start in life.

It is Sadhu, however, who is its most engaging personage. No great stretch of the imagination is required to understand why he is treated as a virtual demi-god by almost all of the town's populace, regardless of religious affiliation. His thoughts and deeds, as put forth in his diary entries - which are definitely the most appealing parts of the novel - drive the plot as much and as meaningfully as do the ideas and actions of his son, the title character.

We are not so fortunate, however, in terms of the work's dialogue, which is often pedestrian and sometimes teeters on the edge of the implausible. To give one of the most extreme examples, it is not terribly believable that a teenage member of Satnam's gang would actually say, "Let's take the initiative by detonating a bomb in a Muhammadan locality!" when planning an impromptu violent attack.

A caution must also be given regarding the remarkable explicitness with which the scenes of sexual activity are handled. This type of treatment seems far beyond the norm for books of this genre, and may well make this novel unsuitable for many members of a younger audience.

These caveats aside, a wide range of readers should find A Sikh Boy quite absorbing and entertaining, bringing a slice of Partition-era middle-class society vividly and convincingly alive.

[April 30, 2008]

Conversation about this article

1: Harinder (Bangalore, India), May 03, 2008, 4:49 AM.

Had our ancestors been wise, they would have tilled their ancestral land in what is now West Pakistan and we would still be in that part of Punjab. Today, we need bright and visionary leaders to show the way.

2: Naveen (Hyderabad, India), May 16, 2008, 5:16 PM.

It's unfortunate that many of our Sikh brothers and sisters suffered so much at that time. West Punjab should be with India, but our leaders betrayed us by giving it to Pakistan.