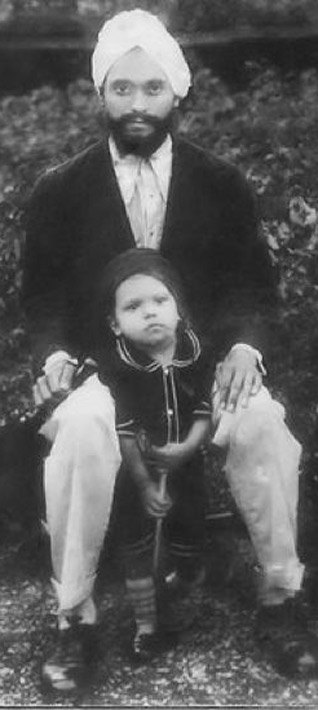

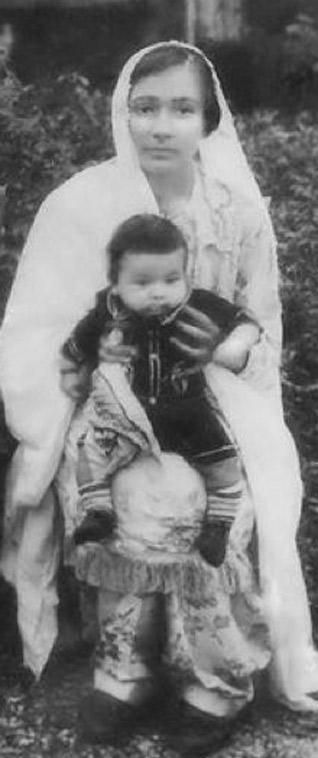

Images, above & below: Kapur Singh & his family. Second from bottom: 6-yr old Ajit Singh (the author's grandfather).

History

Grandpa Relives the Ghadar Days

RAVLEEN KAUR

1913 was the last peaceful year in the life of Kapur Singh, his son -- and my grandfather -- tells me.

My great-grandfather was a typical schoolboy in clay-roofed Kaonke, a village in the heart of Punjab.

A continent away, Punjabi laborers in Oregon, USA, were busy plotting a movement for the independence of the Indian subcontinent. Astoria’s waterfront was lined with Sikh-American millworkers with white turbans and gelled mustaches.

These men met at Astoria’s Finnish Hall to plan the beginnings of a radical movement for independence from the British Raj -- the Ghadar Party. The goal of the party? As historian Johanna Ogden describes, “nothing less than the armed overthrow of British rule in India.”

Whispers of revolution in Astoria’s maritime breeze would blow into dusty Punjab, where 14-year-old Kapur Singh would leave home to join the movement in 1914. Plunging headlong into a radical push for revolution, my teenage great-grandfather would meet with party leaders in secluded homes, help gather materials to bomb the British armory and spend eight months in jail before being released for lack of sufficient evidence against him.

One hundred years later, his eldest son, Ajit Singh, sits cross-legged in a grassy park along the broad mouth of the Columbia, mere feet from where the Ghadar movement was born. A crowd of historians, local politicians and members of the Sikh-American community shade him.

My grandfather -- who I call “Papa ji” -- is wearing a crisp gray suit and a navy blue turban. His hands tremble, but his voice is leathered and strong as he recites a portion of an article he spent the last four years carefully weaving together, a history of his father’s involvement in the movement.

Papa ji reads from a typed document but after a minute disregards it. He tells the audience he had no idea he would spend the three decades remaining until the subcontinent’s independence blacklisted from public school enrollment and barred from steady job employment. The shadow of his father’s small contribution to India’s independence would loom over his young family wherever they went -- and they moved a number of times: from Luck now -- where he was able to complete his diploma in engineering -- to Burma to Delhi to Lahore and beyond.

Kapur Singh never returned to the village Kaonke, worried that police would harass him and threaten his family. Even after independence was won and India and Pakistan were created in 1947, Kapur Singh went without any formal recognition for his role in the movement.

Papa ji has lived in Beaverton (Oregon, USA) for nine years now. Until a few months ago, he had no idea the movement that would change his father’s life had its roots just a couple hours away in Astoria.

He learned none of this through his father himself. Kapur Singh was a cautious man who feared his children would follow in his footsteps. My grandfather never looked into the murmurs of his father’s involvement until he was preparing to move to the United States 30 years ago, when he met Ghadarites who fought alongside his father.

“The old people from the old days told me about it,” Papa ji tells me in Punjabi. “Mere father ne kadi ni dasia, nor did he want to talk to me about it.”

Papa ji’s room smells like coconut oil and worn books. One evening, he peels a rare family portrait out of a dilapidated album. It’s a yellowing image of his mother and father each holding a toddler brother, identical chubby bubbles with wide cheeks and my grandfather’s eyes. My then 6-year-old grandfather sits in the middle with an English grammar book in his arms. Both of the toddler brothers would die in the next five years. In all, Kapur Singh lost four of his eight children before each reached the age of 10.

Seated in a sharply dressed Kapur Singh’s lap is 2-year-old Janak Singh, who died of pneumonia the next year.

“More than 80 years it’s been since (Janak’s) dying, but even now when I think about it, something happens to me,” Papa ji says in Punjabi.

“Janak Singh mar gya,” his father informed 7-year-old Papa ji about his brother’s death.

“Changa, mar gya, I said,” Papa ji recalls, adding that he was glad his brother died because they always fought over a favorite cup. Seven-year-old Papa ji thought death meant going somewhere far away for a while, a long holiday.

One day, a panicked Kapur Singh found Papa ji along the banks of the Irawaddi River, where Janak Singh was cremated. Papa ji tells me he thought that if he waited long enough, Janak Singh would reappear along the river.

Four years ago, I had the grand idea of constructing a family tree. When I found a mention of Kapur Singh of Kaonke, Ludhiana district, Punjab, in a lengthy online listing of Ghadar party members, my grandfather was lit with a new passion for telling his father’s story.

In the afternoons I’d find my grandfather sitting in a lone spot of sunbeam, editing a draft of the article, his wrinkles upturning as he realized I was home to help him type up the research he had compiled. A widower who spends most of his time reclining in his spacious room in my family’s home, praying or ruminating, the story consumed his days.

“Ravleen, what sounds better? ‘Plunged headlong into the movement’ or ‘plunged into the movement headlong,’ “ he asks me. This is how he weighed the hues and shades of his piece, strung together through mentions of his teenage father’s release in a court document, tidbits of narrative from obscure textbooks and out-of-print histories.

It has been two years since his article was bound and finalized, but Papa ji continues to perfect the piece. His sturdy walk has slowed to a limp and it takes longer for him to hear my reply, but speaking at Astoria has put a spring in his step. He hums lilting Punjabi tunes to himself around the house, his voice a thicket of spiritual mystery.

The author, a Beaverton resident and a Portland State University student, writes here as the great-granddaughter of a Ghadar Party activist.. The party’s fight for independence from Great Britain held its centenary celebration earlier this month in Astoria, Oregon.

[Courtesy: Portland Tribune. Edited for sikhchic.com]

October 31, 2013

Conversation about this article

1: Pashaura Singh (Riverside, California, USA), October 31, 2013, 2:09 PM.

Well done, Ravleen Kaur, for this beautiful piece about my Massar ji, S. Kapur Singh, a young Ghadarite. He was a dedicated gursikh who did not seek any recognition from any one even in independent India. I am glad his story is now being told for the sake of the next generations on the 100th anniversary of the Ghadar movement.

2: R Singh (Surrey, British Columbia, Canada), November 01, 2013, 1:08 AM.

My paternal grandfather's Chacha (younger uncle) was also a member of the ghadar movement. He was charged and hanged under the 5th Lahore Conspiracy case. (Bhai Randhir Singh was charged under the 2nd Lahore Conspiracy case.) No official recognition has ever been given to the contribution of the approximate 1,200 Ghadar party members who courted death for India'a creation and independence.

3: Kulbir Dhiraj (Fremont, California, USA), November 01, 2013, 1:52 AM.

Very well written. Proud of you, Ravleen Kaur!

4: Bibek Singh (Chandigarh, Punjab), November 01, 2013, 2:31 AM.

Very touching! More of such stories should be told about the 'real heroes'!