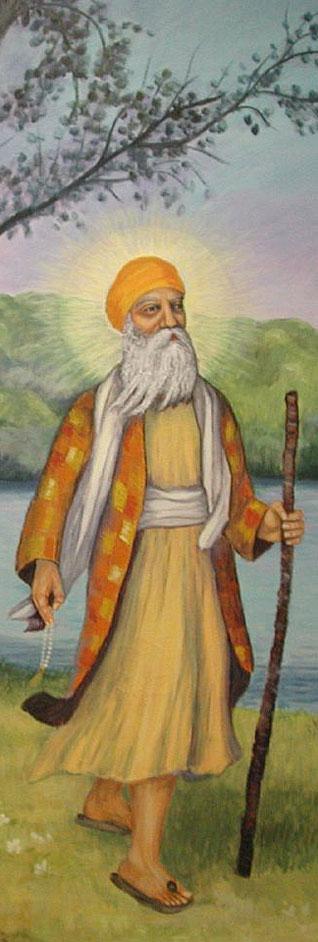

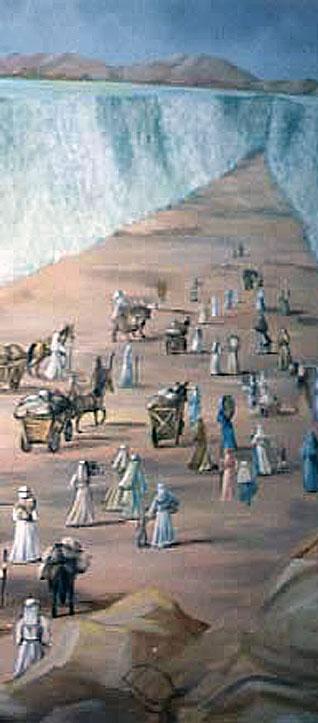

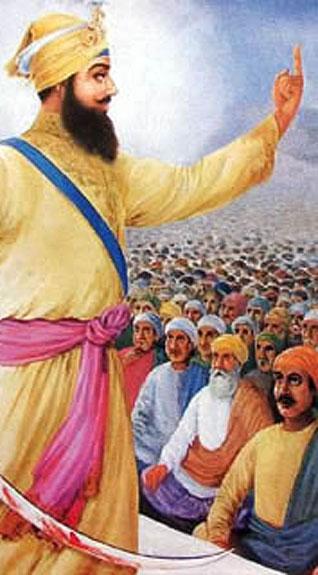

Above: "Guru Nanak", courtesy - Gurumustuk Singh. Below: first from below - Guru Gobind Singh addresses the crowd at Anandpur. Second from below: the ascension of Christ. Third from bottom - Moses parts the Red Sea.

Columnists

Probing the Limits of Scholarship

by I.J. SINGH & GUNISHA KAUR

After a leisurely lunch one day, the postprandial conversation drifted towards what we understand by the term "Religious Studies".

Christian, including Bible Studies, departments are no strangers to academia. Buddhist, Islamic and Judaic Studies are also fairly well represented in universities across the United States, as are programs of teaching and research on Hinduism, though the latter are sometimes masked as India Studies.

Sikhs, too, have jumped on the bandwagon, and several university level programs now exist that explore Sikhism in all its facets.

But what precisely do we mean by such programs of religious study; what exactly is their bailiwick and what is not?

Is it necessary that the academician running the program be a follower of the faith?

Some, but not many religious studies programs have such an onerous requirement. It is not surprising that this should be so; after all, would a non-believer have the sympathetic understanding and empathy necessary to weighing matters of tradition and practice that are not always easily rationalized or logically reasoned out.

Would those who are not followers of the faith be able to ask the questions or perhaps, more importantly, challenge traditional answers? What kinds of questions are appropriate, and what are not? Should we follow the model of scientific exploration where no questions are left off the table?

It seems to us that any and all religions, including Sikhism, have three overlapping elements to them, perhaps each warranting evaluation by a different authority.

First of all is the founder of the faith.

How and when did he live and how he died are certainly matters of honest inquiry. Undoubtedly, some such questions - though minutiae - may be important, while others are trivia, not worth the bother.

Clearly, how Jesus, Guru Arjan or Guru Tegh Bahadur died are significant events because of their underlying cause, and their impact on the faith and society. (Note that their death continues to shape the religion and culture - and not just of the followers - even today, many centuries later.)

On the other hand, how Buddha or Moses left this world might appear to be trivial matters that are devoid of significant interpretation or meaning today. Obviously, there are issues and events that deserve the skill of a historian, and those that do not. Unfortunately, contemporary discussions on religion often neglect this and thus occur in isolation from the other components. Honest or meaningful scholarship is not always the result.

The second concern is that if religions are to become and remain movements that shape the behavior of people, then they are primarily determinants of lifestyle. Religions do this by providing an ethical societal framework to fashion the lives of their followers.

We may highlight the several approaches of different belief systems in the free marketplace of ideas, but only if we tread with sensitivity. In the final analysis, these matters, it seems to us, are the proper bailiwick of a philosopher, psychologist or an ethicist, even a political scientist, and certainly of the followers of other religions, but hardly the primary concern of a rigorous historian.

As an example, a historian might note the murky evidence on when and how the caste system of Hinduism appeared, or exactly how and when the Jewish and Islamic faiths instituted requirements of "kosher" or "halaal" preparations of their food, but it is outside the historian's purview to come out with a value judgment on these practices, condemn them or argue for specific changes in them. These matters should be debated, and reformations of the practices are possible, but only by the insiders - those who belong to the faith.

An internal debate should not only be welcome, but is necessary.

Finally, we come to matters that, in our opinion, perhaps lie totally outside the domain of the historian. They belong entirely to people of faith, and to subject them to "scientific rigor" would diminish both the academic historical process as well as faith.

Let's work through a few examples:

For Sikhs, Guru Nanak's revolution begins with his emergence from the River Bein and his words on Truth and Love. The first Master then shared his revelation, or divine words and insight; his message was further elaborated by the succeeding nine Masters of the faith, who spoke in his name and authority.

Guru Nanak's own words, Jaisi mai aavai khasam ki bani, taisara kari gianu ve Lalo, are very clear in meaning - "As the divine words are revealed to me, so do I utter them!"

But what exactly happened when Guru Nanak was in the river? The historian, from his perch of realistic objectivity, may conjecture that Guru Nanak spent the time unseen somewhere near the river, perhaps in conversation with some other great minds of the day, and that focused his thinking. Persons of faith take umbrage at such formulations and argue that the Guru did indeed receive divine revelation.

This belief in revelation is the foundation of Sikh theology, as it is of many other faiths as well. Yet, it cannot be proven or unproven by the historian or the ethicist.

Let us take another example from Sikh belief and history.

Sikhs believe that in 1699, at a historic moment in the faith, the tenth Master, then Gobind Rai, called his followers from all over the country to a remote village in Punjab. Perhaps around 80,000 came. The Guru appeared before this vast gathering brandishing a naked sword, and asked for a head for the cause.

Many looked away and some surely slunk away. After much trepidation, one man rose to offer his head. The Guru took him away to a nearby tent, and moments later reappeared with a sword dripping with blood.

He then repeated his call for another head. Many who disappeared must have thought that the Guru had lost his mind, but another man rose to offer his head. The Guru took him, too, into the tent, and came back to repeat his call for a third head. The process continued, until five Sikhs had thus offered their heads.

The Guru then went back to the tent and moments later reappeared with the five volunteers, alive and well, dressed in the uniform of the new Sikh. These five were the first Khalsa and are enshrined in our collective memory as the "Five Beloved" Sikhs.

They then, in turn, initiated the Guru into the new order.

Thus was a new nation created!

But what exactly happened inside the tent?

The historian, again from logic and reason, opines that the Guru might have sacrificed goats when he came back with his blood-dripping sword. (Some historians believe that the sacrificial animals were sheep or chickens.) People of faith reject such formulations and argue that the Guru, with the power of God in him, beheaded the men and then revived them.

We cite these two examples from Sikh belief, because the events are seminal to the Sikh sense of self, and because these are queries that repeatedly come up in the cynical questioning of academically rigorous, otherwise excellent, historians.

Now, are these matters such that they can be resolved rationally? Yes, they can, but not by logic alone.

Think with us very briefly about the religious beliefs of some of our neighbors.

Was there a "burning bush" and did the sea part as believed by some? Was Jesus born of a virgin? Did he transform water into wine? Did he rise from the dead? Did Jesus (and his mother Mary) ascend to the heavens bodily, spiritually, or both? The dogmatic position says yes to all of these. Is there a heaven for Muslims with a guaranteed supply of virgins to a martyr? And would all non-believers burn in hell forever?

No matter how they arose or how they might appear to us, these matters are central to the belief of many of our neighbors. These have become matters of dogma now.

We would argue that, of all the issues that we have raised here, none can be answered by honest historians, for they essentially lie outside their area of competence. There can never be any objectively verifiable data to unequivocally endorse any of them. Only one idea - that unbelievers might eternally rot in hell, if there is a place called hell - may be explored and questioned, and that, too, not by a historian, but by a philosopher or an ethicist, because it treats humanity differentially.

In the final analysis, there are two issues. Why are such critical matters framed in language that is logically inaccessible to intellectual rational analysis? And if they are to be explored, who should do the parsing, if not the historian?

Let's come at these matters somewhat tangentially.

One must start with the obvious fact that no one knows exactly what happened in the river before Guru Nanak re-emerged after three days. What we do know, however, is that the message that he brought back with him is one that lies deep within the hearts of millions of followers to this day.

The questions on the beheading of goats, chickens or men on Vaisakhi 1699 are similar and not so easy to resolve either, but I think we do need to face them.

None of the Gurus, from Nanak to Gobind Singh, ever practiced miracles or magic spells; in fact, they categorically rejected such showmanship. How, then, could Guru Gobind Singh have gone against his own teachings and those of all the earlier nine Gurus?

Again, one must start with the obvious fact that no one knows exactly what happened to Guru Nanak in the river, or in the tent where Guru Gobind Singh took the five volunteers who came forward to give their heads.

In their infinite wisdom, the Gurus chose to keep us in the dark on those issues ... for good reason, we're sure.

We submit that these are not matters that can or need be resolved by historically verifiable facts in evidence. Then why is the unverifiable language of miracles used to capture such events?

What it tells us is that the magic of the moment of Guru Nanak emerging from the river, or of Vaisakhi 1699 was such that words could not capture it. The only alternative was to resort to imagery that transcended human realities and their limitations.

This matter is exactly like some others mentioned here - the burning bush, the parting of the sea, the virgin birth, the rising from the dead, or the being lifted up to the heavens both bodily and spiritually - that are found in other faiths around us.

For the believer, these are matters of dogma, but, essentially, these are all efforts to capture the magic of the moment. A literal rendering of such metaphorical language does a disservice to the event and its rendition, as also to the faith. There can be no rhyme or reason to attempt a parsing of metaphorical language in order to deduce facts of historical events. It cannot yield the "truth of history".

The message of Nanak resonates with millions and defines them even today, more than five hundred years later. That the Vaisakhi of 1699 was magical is also undeniably true - from it arose a nation, and a people that, even now, three centuries later, are still willing to walk the path and the extra mile for the Guru. This is magic much greater than chicken, lambs, goats or the beheading of five people and their revival.

When we look for historical evidence in order to reject or verify momentous events like these and translate them to our limited human experience and language, we diminish the magic of the event and rob the moment.

We suggest, therefore, that such events are perhaps best not analyzed, but need to be accepted by our hearts and souls - somewhat like love, for instance.

To overanalyze love is to kill it.

Helen Keller reminds us that "The best and most beautiful things in the world cannot be seen or even touched - they must be felt with the heart".

There is no need for anyone to try and analyze or guess what happened to Guru Nanak in the river or what might have happened in the tent between Guru Gobind Singh and these five Sikhs who are remembered every day in Sikh tradition.

This does not mean that matters of dogma need not be explored. Metaphorical language needs and deserves continual reinterpretation every day - by the follower, however, and not by historians. Their tools, essential and formidable as they are, are not suited to the purpose here.

We are not arguing for impenetrable fences between the worlds of faith and intellect, but for spanning the difference with more sensitivity in our explorations

We need to keep in mind that religions deal with a reality that transcends the intellect. An understanding of this reality demands that we accost it with the dual lenses of reason and faith; neither alone is adequate.

Religions, their dogmas and their interpretations are essentially stable, but they do not lie still like stagnant waters.

March 18, 2008

Conversation about this article

1: Harinder (Bangalore, India), March 19, 2008, 9:19 AM.

There is so much of the world that we don't know of even today. The Dark matter, other dimensions, the Big Brain theory - all defy conventional Newtonian science. That our Gurus did these feats needn't surprise us.

2: Harpreet Singh (Cambridge, MA, U.S.A.), March 19, 2008, 3:40 PM.

There may be a different way in which we can think about the Janamsakhi accounts of Guru Nanak's life in relation to other mythological events that you mention from non-Sikh traditions. Janamsakhis do not have a canonical status within Sikhi. The Janamsakhi genre does not carry the same authority in Sikhi as the Torah or the New Testament do in Jewish and Christian traditions, respectively. This distinction is vital. If a historian denies a popular event from Guru Nanak's life recorded in Colebrook or Bhai Bala's Janamsakhi, it does not create theological issues for the Sikhs. Whereas, if a historian repudiates the birth of Jesus from a virgin mother or questions his rising from the dead, it has serious theological consequences for a Christian. The second thing that I want to point out is that the historian is not just using "logic and reason" in his or her evaluation of traditional accounts. The historian always - and I want to emphasize the "always" - brings certain presuppositions to such a scrutiny. These presuppositions drive the historian's methods of research and what he or she includes and excludes from the available data. There is no such thing as "objective" scholarship and this is an accepted fact in academia today. Lastly, it appears that you have framed your discussion around belief, rather than faith. There is a major difference between the two. Wilfred Cantwell Smith, in his "Faith and Belief: The Difference Between Them", defines faith as "a direct encounter with God - mediated, no doubt, by the sacraments or the doctrines, or the moral obligations involved, but significant precisely because it transcends these, and enables the person to transcend them" (1998: 11). On the other hand, he defines belief as "the holding of certain ideas. Some minds see it as the intellect's translation (even reduction) of transcendence into ostensible terms; the conceptualizing in a certain way of the vision that, metaphorically, one has seen; at a less spontaneous level, that one hopes to see ... we strictly use the term for an activity of the mind" (1998: 12). W.C. Smith claims that it is possible to believe without faith. He adds elsewhere that "belief" is a distinctly Christian category and it does not exist in other traditions with the same emphasis. For Guru Nanak and his Sikhs, the whole vision of the world that is centered around God and his shabad (revelation) is so vivid, that belief (as defined above) has no place in it. The Sikh does not require doctrines and beliefs in the same manner as a Christian to live her dharmic lifestyle. In this sense, as Sirdar Kapur Singh has noted ("Sikhism and Conformism"), the Sikh Rehat Maryada is not the essence of Sikhi, it is merely the fence that has enabled the Sikh community to survive. With this aspect in mind, I think that your article, instead of being framed in Christian terms of belief, could have been framed from a different theological position in which you spend more time discussing how faith is central to Sikhi and the historical methods of the west require serious amendment in order to have a nuanced understanding of Sikhi. This should not be taken as a major criticism; the questions that you raise are very important and necessary and I am glad to see your response to them.

3: Chintan Singh (San Jose, U.S.A.), March 19, 2008, 6:40 PM.

I believe our problem is that we have very few scholars and they have to please both the Sikh community and their acedamic colleagues, which has not been possible. In trying to keep one happy, they make the other unhappy. If they be rational and act with intellect, they start walking on the community's emotions and faith. If they act emotionally and be sensitive to the community's faith and feelings, they are not able to meet the academic standards and thus hurt their career. A balance of both is needed and I think that can be created if we have, firstly, a larger pool of scholars. Unfortunately, historical and religious studies does not seem to be a stable career for an immigrant community which is primarily concerned about being able to live the American or Canadian dream and be able to provide for their families. Our institutions and gurdwaras need to encourage the youth in taking up careers in these non-conventional fields by scholarship awards and insightful career seminars. I also refer to your last article in which you stress the need of our scholars to interact with the mass community by coming in and presenting their research at gurdwaras. They need to make the findings of their research simple enough for a common reader like me to understand and appreciate rather than keeping it exclusive for the elite and scholarly folks. I would imagine, if our scholars worked harder in keeping good relations and PR with the community at the grassroots level and periodically presenting their research to a larger audience in a simpler format, they would reduce the risk of making the community upset when they analyze sensitive historical incidents such as the Vaisakhi of 1699. I am personally a strong believer of the saying, "It does not matter what you say, but how you say it." Last but not least, I think our community still has a long way to go in negotiating the correct type of agreements with the Universities when they try to set up the academic chairs and professorships. A lot of community resources have been directed in the past decade or two in setting up University Chairs. One of your much earlier articles indicated a couple of chairs are still lying vacant in North American universities. That, I believe, is also a reason for the community's discomfort in explorations on Sikhism in the ivory towers of academia.

4: Gurdit Singh (Kansas City, U.S.A.), March 19, 2008, 7:18 PM.

Thanks to Harpreet for raising some important distinctions and adding to an important discussion started by the authors. I would like to add that not all historians are alike in their use of the so-called "western method" in analyzing stories similar to those described in the janamsakhis. In stark contrast to Hew McLeod, whose rigid and hyper-skeptical views often make him render tradition as "frequently unreliable", Richard Eaton, a renowned historian of Indian Islamic traditions, has a very different attitude towards traditional Indian sources of biographical knowledge. Unlike McLeod who rejects many of the stories in the janamsakhis (which he calls hagiography as opposed to biography), Eaton embraces hagiography as an integral element in reconstructing the medieval history of the Deccan. Eaton views biography and hagiography as a part of the same continuum. In fact, he utilizes several hagiographical accounts to reconstruct the biographies of eight figures, some pre-dating Guru Nanak, whom he deems central to the social life of the Deccan (see his _A Social History of the Deccan, 1300-1761: Eight Indian Lives, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2005). Moreover, the janamsakhis remain some of the best repositories of several important sources of knowledge: * They are some of the earliest examples of Punjabi prose (not to mention elements of drama); * A Janamsakhi like Miharban is one of the earliest examples of theological exegesis (parmarth) in the Sikh tradition; * They are a treasury of myth, whose social and psychological significance has yet to be meaningfully understood; * Some of them contain what Dr. M.S. Randhawa calls the first examples of "Sikh Art"; * The earliest janamsakhis like Puratan and Miharban provide useful insights into the social worlds of the Sikh communities, during the 100 years after Guru Nanak's joti-jot; and * Since some of the janamsakhis are, perhaps, products of communities which later come to be labeled as heretical (e.g., Handalis, Minas), they provide a useful lens through which to view the evolution of dissent in early Sikh history.

5: Ravinder Singh (Columbus, Ohio, U.S.A.), March 19, 2008, 11:30 PM.

A couple of points: First, it would be difficult - if not impossible and inadvisable - to expect historians to just stick to dry-as-dust facts. Value judgment is woven into a historical narrative by its very nature. History is, according to Thucydides, Philosophy taught by examples. Second, intellectual rigor can coexist with deep faith. I am sure those who analyze the chemical reactions that give rise to love still feel it(love) in their hearts. Defining events like the Vaisakhi of 1699 transcend mere historical analysis.

6: Harpreet Singh (Cambridge, MA, U.S.A.), March 20, 2008, 1:00 PM.

Thank you, Gurdit, for providing additional insights on the Janamsakhis. Two additional points that I would add to your list are that Janamsakhis have served an important role in providing self-definition to the early Sikh community; and even more importantly, they have served as a counter-tradition to narratives used by Hindu traditions to assert their superiority. Richard Eaton and his colleague Carl Ernst have indeed transformed their field of scholarship when it comes to South Asian Islamic traditions. The malfuzat accounts of Sufi shaykhs figure prominently in their reconstructions of history. The malfuzat genre, however, does not correspond well with the Janamsakhi tradition. Take for example, the "Fawa 'id al-Fu'ad" - an account on the life of Shaykh Nizam ad-Din Awliya - a malfuzat compiled by Amir Hasan Sijzi (b. 1254). Here, the Shaykh himself authorized and oversaw the production of the malfuzat. He also made corrections to Sijzi's account of the Shaykh's discourses and his life as a Sufi pir and as a murid of Shaykh Farid. Therefore, it becomes much easier for the historian to use it for biographical purposes. At the same time, both Eaton and Ernst often wrestle with the issue whether a particular malfuzat account is "authentic". The important point that Gurdit makes is that they do not dismiss such accounts completely in their reconstruction of history. Another question that I want to raise is concerning the viability of the category of hagiography, which includes a varying list of literary genres, and whether it helps us think adequately about the Janamsakhi tradition. It, perhaps, would be useful to look at the theorization of malfuzat, Hindu and Jain puranas, Buddhist vamsas, etc. in order to create an adequate theoretical model for the study of the janamsakhi literature.

7: Manbir Singh (Irvine, CA, U.S.A.), March 20, 2008, 4:47 PM.

"Metaphorical language needs and deserves continual reinterpretation every day - by the follower, however, and not by historians." This statement, for me, counters the seemingly endless need for certain scholars to have an academic and objective explanation for all events/concepts in religious history. The questions posed by the author can only be subjectively answered by the adherents of a particular Faith - based upon their own understanding and life experiences. In Sikhi, an adherent's interpretation of the seminal events of Sikh history, and their meaning, may be attributed to the Guru's grace upon the particular adherent, and affirmed by the adherent's own unique experiences. In addition, the concepts of God and Love are abstract. They cannot be quantified, ascertained or analyzed by a scientific method. They must be felt and experienced by the heart and soul, instead of being relegated to the confines of one's mind or the pages of an academic journal. In his last article, I.J. Singh summarized this very theme by sharing the motto, "Keep it simple, stupid". In the above piece, he reinforces this concept by incorporating Helen Keller's quote and the fact that, "to overanalyze Love is to kill it"? I concur that the questions posed in the above piece transcend intellect and cannot be determined by reason alone.

8: I.J. Singh (New York, USA), March 21, 2008, 10:01 AM.

In the scintillating discussion on our column a point has emerged that deserves additional comment and exploration. It is true that Jamamsakhis occupy an important niche in Sikh tradition but they are not entirely historically verifiable accounts, nor are they meant to be. They are like the hagiographic accounts of the virgin birth or turning water into wine by Jesus, or parting of the Red Sea by Moses. A crucial difference that we should have noted in our column is that while many of these miraculous and mythological events are fundamental to the belief of some other faiths, such renderings (Janamsakhis, for instance) are not the basics of Sikh doctrine that every Sikh must believe. I also understand that historical explorations, like those in science, are never entirely objective, and hence are never without bias. Objectivity, in fact, exists only as different levels and degrees of subjectivity. The major thrust of our exploration remains that many of these efforts in hagiography that mix art, mythology, poetry and qualities of the heart with a smattering of history are not really amenable to the tools and interpretations of history with, as T.S. Eliot said, its cunning passages and contrived corridors. And that this comment applies not only when we explore Sikhism, but equally well when other religions are subject to scholarly parsing.

9: Rawel Singh (New York, U.S.A.), March 23, 2008, 10:43 AM.

May I suggest that it is possible to harmonize the religious dogmas and today's critical thinking if we keep the time factor in mind. This has also to do with development of the human intellect with time. We must accept that drama is probably the best way to put across a concept that may not be easily understood. If the historian keeps that in mimd he would be able to present a work that is more widely acceptable. Take the case of the Vaisakhi of 1699; does it matter what the Guru did in the tent. The Five Beloved ones offered their heads, the last four in spite of seeing the blood dripping sword and that is what matters. I also draw parallels between God talking to Adam in the Garden of Eden, to Moses on Mount Sinai, to Mohammad in Arabia or to Guru Nanak when he disappeared in the River Bein. In all cases, it is sought to be shown that God revealed to them directly. May I suggest that in all cases the purpose is to show the revealed nature of the respective religions. But as the author has said, Guru Nanak has made it very clear by stating that the revelation came to him through the Word, 'jaisi main aavay ...' So, the Sikh faith accepts the story as a potent metaphor. I submit that the others are the same. They however encounter some difficulty because their scriptures and history are woven together in the same document(s). Some people therefore question the "tampering" with their scripture, but that is a different subject.

10: Ravneet K. Tiwana (California, U.S.A.), March 26, 2008, 4:08 PM.

Thank you for addressing the concept of "revelation". Ultimately, "faith" can only be understood, not proven. I think many religious communities negatively react to religious scholarship, produced by both believers and non-believers, because they feel this scholarship is an attempt to question the "truthfulness" of their faith versus understanding its meaning. In Sikhi, for example, interpretation of religious history is intimately related to faith and practice. Therefore, scholarship that claims "truth" and challenges faith based on academic "reasoning" of historical "facts", is generally viewed as a personal and communal attack. Hence, scholars should understand that separating the "meaning" of faith and "facts" of historical occurrences is a good tool for "analysis", but ultimately in religious practice they come together. Therefore, religious scholars have an ethical responsibility to be mindful and sensitive to rigorously understanding the communal meaning of faith, incorporating this "meaning" into their work on historical "facts", and being aware of the limits of academic reasoning.

11: Roma Rajpal (Santa Clara, U.S.A.), March 27, 2008, 1:13 AM.

Another amazing article! Extremely thought-provoking. I believe it comes down to each person's own ideas, understanding, knowledge, interest, passion, love, faith, etc. Is understanding/analyzing the supernatural events of Sikh history helpful? Nothing has been proven and it never will be. So, it all depends on one's faith. What do you want to believe in? How is it important to the big picture? Would it change your beliefs if the truth was something else? When I was a young girl, I used to think a lot about the Amrit ceremony and the panj pyaare "story" and I refused to believe that Guru Gobind Singh Ji would even ask for someone's head, let alone kill goats or men or whatever. This belief is strong even today. It just doesn't feel right to me inside. Something else must have happened which I (we) don't know. And, whatever it was, it can't involve killing or scaring anyone, since to me, that does not connect with the Guru at all. All that is important to me is that the Guru was trying to create a stronger, fearless, selfless, and courageous community whose members would stand up against injustice, tyranny and oppression. He did so much for mankind and left a better world for us. I believe in our Gurus who were sent by God to lead and guide us ... I believe in their words and no one else's. And this comes from my heart.