Art

Saint-Soldiers in Colour - Sikh Calendar Art

by I.J. Singh

Art and architecture have long been the neglected stepchildren of Sikh scholarship. Much has been written about Sikhs - their theology, history, politics, culture, etc. - but not about their art or architecture.

I was initially tempted to title this essay "500 years of Sikh Art," and proceed accordingly. That, I saw, would be too ambitious an undertaking. The domes and arches of gurdwaras, perhaps inspired by Islamic and Buddhist architecture, are distinctly unique. The bas relief and the intricately inlaid art work that adorns the walls of many gurdwaras, particularly the Golden Temple, as well as the copper and gold leaf gilded structures deservedly elicit oohs and ahs from hordes of tourists from all over the world.

Sporadic, incomplete attempts to define and discuss Sikh art exist in the early efforts by Surjit Hans and Madanjit Kaur, brief references by Patwant Singh in his book on the Golden Temple, and a limited foray by the California-based Sikh Foundation in one issue of their now defunct quarterly Sikh Sansar. Museum-quality Sikh art has been seriously discussed and tastefully presented by Kerry Brown (1999), Susan Stronge (1999), B.N. Goswamy (2000), and most recently by B.N. Goswamy and Caron Smith (2006). Laurie Bolger (2006) has reviewed the latter; I, too, have undertaken a general discussion of art, faith and history (2006).

Then I thought of the first of several talks that I recently had with a bunch of largely non-Sikh art aficionados. They raised the questions: what is sacred art, and what would be Sikh sacred art?

Hew McLeod in his 1991 book, Popular Sikh Art, starts with a useful working definition of Sikh art. It could be produced by Sikh artists, be created under Sikh patronage, offer a distinctive Sikh style, be produced in a territory dominated by Sikhs, and/or highlight Sikh themes.

Surely, iconography in Sikh art is just as commonplace as it is in Christian, Hindu or Buddhist traditions. This is so, even though there remains no record of any painting or any description of the physical attributes of any of the Guru-prophets of the religion. No replica exists of the image of any Guru on canvas, in clay, stone or any other media. I know some historians contend that a likeness of the ninth Sikh Guru, Tegh Bahadur, was painted during his lifetime. If so, it no longer exists.

In Sikh teaching, what is important is the message, not the flesh of any Guru that trod the earth. Given this very straightforward idea, I could argue that there can certainly be Sikh art, but none that, by any definition, is "sacred." Good art may evoke reverence, but that is merely the manifestation of extreme appreciation, adoration and passion. What constitutes excellent art remains an enigmatic question with no easy answer. For instance, some very sophisticated minds may find Andy Warhol superb, while others may not. Many see redeeming value in the creations of Maplethorpe, while just as many find them an abomination. And most of us including myself, unschooled as we are in the artistic world, belong to the "I know what I like" school of art.

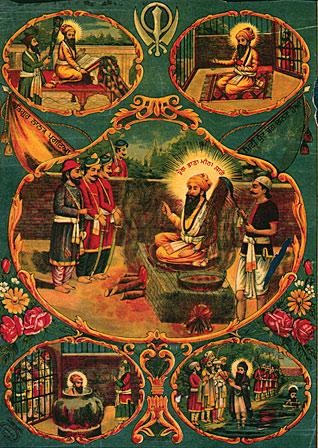

What I want to do today is to take note of what some might consider the least and lowest common denominator of art on Sikh themes -- art that has, through the years, graced calendars and posters. Representations of Sikh Gurus in all kinds of ridiculous settings, some surrounded with haloes of flashing lights, are not rare in gurdwaras and marketplaces all over the world that cater largely to Sikhs. Whether as images of Jesus, Madonna (the one who inspires saints, or the one who arouses baser passions), Marilyn Monroe, Elvis the Pelvis, or as spreads in Playboy, calendar or "bazaar" art is never very sophisticated, or intellectually and emotionally gratifying. But this art form exists in all cultures, and has defined mankind since we were cave-dwellers. So it can't be entirely pointless and shouldn't be summarily dismissed.

My interest in this topic arose from two tantalizingly titled books published some years ago, Popular Sikh Art by Hew McLeod (1991) and Sikh Heritage in Paintings by K.S. Bains (1995). The two differed widely in their scope and treatment of Sikh heritage, and brought home to me how Sikh calendar art seems to be evolving.

McLeod's book took form when he saw Hindu Epics: Myths and Legends in Popular Illustrations by Vassilis G. Vitsaxis. At first glance, any minimally cultured reader would cringe at this collection of "bazaar" art. Readers who are aware of the controversy surrounding McLeod's writings would further wonder if these garish examples of "art" for the semiliterate - his collection is truly tawdry - were collected to embarrass the Sikhs. Such gut responses, however, should be resisted.

In analyzing 54 examples of such poster art, McLeod presented a historical survey of Punjabi art and the influences on it - whether Mughal, Pahari or British. Tracing a simple, coherent story of Sikh history through posters, he explored how the predominant Hindu society has molded this art form. He also identified Lockland Kipling, the father of Rudyard of Jungle Book fame, as the first collector of popular Sikh art.

In McLeod's collection, the artist is not always identified; perhaps he was not always known. Not all examples are by Sikh artists, thus accounting for the mix of Sikh themes with non-Sikh perceptions. It is easy to see where attempts were made to mythologize the Gurus, Sikh martyrs, or history.

The depicted characters often appear simplistically two-dimensional, in simple but vivid colors. Blue, saffron and yellow dominate. Baden-Powell (quoted by McLeod), speaking of the Punjabi had noted: "...his colour is often exaggerated but it is always warm and rich and fearless." Village and folk-art is undoubtedly vibrant and unrefined, and it shapes and defines how folks view themselves. McLeod also included examples of the richness of Punjabi embroidery, costumes, and designs. He finds little subtlety in their art, but notes that Sikhs, predominantly fighters and farmers, had little peace since the inception of their faith.

Although he presented inferior art, McLeod's work was the first serious interpretation of Sikh pop art. More sophisticated artists like Sobha Singh and Thakur Singh have also produced their share of popular calendar art that was not included by McLeod, because their technique and approach placed them outside the pale of ordinary folk art. In 1969, Arpita Singh, working with Khushwant Singh, produced some interestingly detailed illustrations to accompany hymns of Guru Nanak. Har Dev Singh (1987) created abstract art to the poetry of Barah Maha Tukhari of Guru Nanak, which celebrates the seasons of the year. They produced modern popular Sikh art but not poster art, so McLeod did not include them.

During the past three decades, under the aegis of the Punjab and Sind Bank and, later PSB Finance, there has been a significant change in the quality of poster/calendar art on Sikh themes. It is a lineal descendent of the same genre of art, and the 1995 book by Bains is a collection of it. It is much easier on the eyes, showing improved technique and perspective. Although this is pop art, McLeod did not include it.

In the book by Bains, there are 119 paintings in all. Sikh history, from the Gurus to Maharaja Ranjit Singh, is well represented. There is even one plate from the period of the Gurdwara reform movement. A set of paintings illustrates the afore-mentioned Barah Maha Tukhari. Sikh themes have been wisely chosen - such as the dignity of labor, equality of women, love of mankind, helping the needy, Kaar sewa, Amrit ceremony, etc. Each scene illustrates a lesson from Sikh history, and drives it home clearly and forcefully, with an informative commentary in English describing each panel. An appendix provides translations into Punjabi and Hindi.

In this book there are no mixed themes, nor Hindu idols of gods and goddesses, as in McLeod's collection. The art is much more sophisticated, the artists significantly better. Ten artists - both Hindu and Sikh - are represented. They are listed on the inside cover of the book, but each painting's maker or his style are not individually identified. The glossy reproductions are superb and expensively produced; they clearly highlight the labors of first-rate skilled artists, devoted to their craft.

Besides the natural embarrassment suffered by a cultured mind when confronted by inferior art such as presented in McLeod's work, Sikhs have been reluctant to endorse depictions of Gurus for two sensible reasons: no authoritative likeness of any Guru exists, and the danger that a picture will become an icon. The latter would be contrary to Sikh teaching.

However, popular art, like its written counterpart - even dime store stuff - remains a powerful window into popularly prevailing notions and understanding of a people, in this case Sikhs, their Gurus and Sikh history. In that sense, they are no less valid sources of history, social and cultural constructs, than many first-person accounts of oral history recorded by non-historians. History doesn't come to historians in neat packages. They create the discipline by mining data from such artifacts as art, diaries or letters. Notwithstanding Andy Warhol, pop art and pop literature are important to both defining and understanding a people.

Calendar art, which illustrates parables and events from Sikh history, thus becomes a logical continuation of the illustrated janam-sakhis, which remain important secondary sources of Sikh history to academic historians.

Both books deal with Sikh calendar art, but there is such a world of difference between them in terms of their quality as well as their thematic content, that one wonders if they are talking of the same religion. The problem, of course, is rooted not in any dichotomy in Sikh history or heritage, but in the Indian society, which remains highly stratified along lines of education and economics. McLeod presents Sikh art that is abundantly found in small towns and the countryside even today, whereas the Punjab and Sind Bank book derives its inspiration from the very rich tradition of Christian art in the best of European cathedrals.

The story of Sikh bazaar art does not end with the works of McLeod and Bains. Over a million Sikhs now live outside Punjab, largely in Britain and North America. And they have measurably impacted Sikh calendar art as well. Since 1999, the year that celebrated 300 years of the Khalsa, the California-based Sikh Foundation has annually produced calendars highlighting a variety of Sikh motifs. Museum-quality art is reproduced from the Kapany collection, contemporary works of Arpana Caur as well as the U.K-based twin sisters, Amrit and Rabindra Kaur. The Sikh Foundation's 2007 calendar showcases the illustrations of India-based artist Sukhpreet Singh, who has captured in stunning detail the childhood games that Sikh boys and girls play while growing up in Punjab.

Future Computing Solutions (Sikhpoint.com), an online company, has just released its 2007 calendar. This multifaith calendar focuses on the major religions of the world through the crisp, clear and eye-catching line drawings of the USA-based architect and artist, K.P. Singh. Each panel contains a sketch of an important event or monument of one of the many faiths of mankind; its meaning is further elaborated by an appropriate citation from Sikh scriptures. In 2006, I saw a calendar highlighting suitably clad Sikh male models. In this new Sikh art, the influence of western techniques, motifs and esthetics is unmistakable.

It seems to me that Sikhs outside Punjab have carried Sikh calendar pop art a magical step forward from the quality of art discussed by McLeod and Bains, which is commonly found in Punjab and its gurdwaras even today. Sikh Foundation and Sikhpoint.com have produced calendars with Sikh art that is relevant to the times, which even the most sophisticated viewers would enjoy displaying in their homes and offices.

McLeod concluded by opining that the current struggle of the Sikhs in India will also find expression through pop art. In that, he is right. Bains' selection included one painting from the days of the Gurdwara Reform Movement of the 1920's. The events of 1984 increasingly find expression in the poster art that is found in most homes and gurdwaras today.

Sikh history has been most colorful. From the Gurus to martyrs like the sons of Guru Gobind Singh or Baba Deep Singh, figures larger than life have dominated the canvas. They live through Punjab's folk art, however unformed it may appear at times. In the newer Sikh calendars, each panel presents an accompanying parable from the lives of the Gurus or martyrs, illustrating some vignette or lesson of Sikh history and religion.

Admittedly, what emerges is a straightforward account of Sikhism as the Sikhs and their friends see it. It is not a historian's view - weighed, measured, distilled and refined, yet imperfect. But it continues to nurture our connections to our roots.

The two samples of early Sikh Calendar Art shown on this page are from the Twin Studio Sikh Art archive, as reproduced in a publication titled "Images of Freedom - The Indian Independence Movement in Popular Indian Art" by Amrit and Rabindra Kaur Singh. Published by Indialog. ISBN 81-87981-35-0. Available through mailto:%20fineart@singhtwins.co.uk