Columnists

Dara Singh

T. SHER SINGH

DAILY FIX

Wednesday, July 11, 2012

Growing up in a newly-minted India, far from the land of my ancestors, the dichotomy in my upbringing left a gnawing hunger in me, even as a child.

I inherited an intense pride in being Sikh and Punjabi from my parents, but strangely no bitterness from the recent cataclysm they had left behind in a metastasized Punjab.

On the other hand, we were living in Patna and Bihar, a city and a state which had no indicia of a Sikh or Punjabi lifestyle, or any public display of their history or culture. The world at home found no emotional support in the world outside.

It created a deep yearning for things I could relate to emotionally - for things that gave me a personal sense of belonging. I sought out and savoured every little tidbit I could find and squeezed out of it every drop of inspiration I could find.

Sure, there were the weekly visits to the Takht Sahib a few miles away for the Sunday morning service. It filled a necessary part of my life, but still left a huge hole - one that could only be filled with what we term culture, because it is culture that brings all the disparate things in our lives together.

Without culture, we remain disjointed.

And disjointed I felt, always hungering for the slightest connection I could find to Punjab.

The periodic kavi darbars - song & poetry concerts - held on gurpurabs were mesmerizing, even to a six year old. The language was obtuse but the sights and sounds and accents were enticing, and merely proved to salivate me for more.

I was forever looking for Punjabi song and dance. Remember, it was an age before basic radio - and any airwaves we were able to catch were in Hindi. It was before television. Gramaphones were scarce - we didn’t have a His Master’s Voice.

Punjabi films turned up in town at the rate of about one every year, and we lapped it up in no time: the earliest one I remember is Jugni. Guddi and Jeejaji came much later.

And then there were the folk-singers: Hazara Singh Ramta, Surinder Kaur and Asa Singh Mastana who were guaranteed every Punjabi soul within miles at every performance.

The once-a-year appearance of a Bhangra group for Basant or Lohri left us in a tizzy.

But the one that grabbed me the hardest was Dara Singh.

Because he was in the papers, on the front pages. Posters of him, poised to strike like a cobra, were every where. He was the single-most public acknowledgement for me by the world at large that indeed there was a Punjab out there somewhere and it did matter.

I was no wrestling fan, but that didn’t prevent me from hero-worshipping this demi-god. I looked around me and noted that everyone was gaga over him. It fed into my personal hero-worship of him.

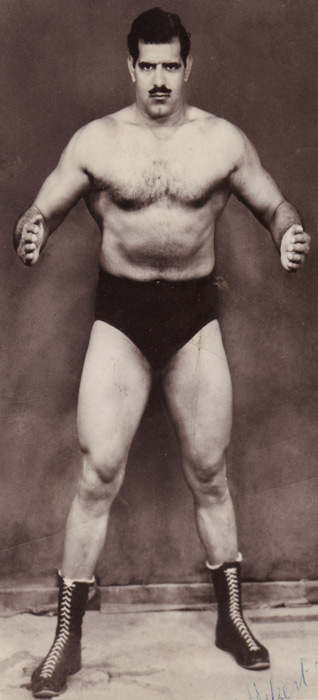

I followed his exploits as much as I could. The scantier the information available, the hungrier I became. There was only one image of him available and it was not only iconic, it pervaded everybody’s consciousness stronger than any film-star or deity.

With arms out-stretched, body crouched and cocked, his muscles and sinews taut and ready to spring, his eyes piercing right through you … it was something no cricketer, not even Nari Contractor, no tennis player, not even Rod Laver, no hockey player, not even Dhyan Chand, no boxer, not even Rocky Marciano, could do.

I too, like all other boys at school, had a scrap book at home with photos from newspapers, magazines and playbills clumsily cut-out and pasted in them.

Dara Singh had pride of place. On the cover and on the very first page inside. The only other wrestlers featured in the tome were King Kong - I had assumed then that he was King of Hong Kong! - and the great Gama.

With all this hero-worship and nothing to feed it, imagine my delight when news hit us that Dara Singh was coming into town. I was no more than 6 years old then, and come hell or high water, I was going to see him.

My father was not into wrestling, and didn’t think it was a good idea. It was something the servants would go to, not respectable people. I must have created a perfect storm because he ultimately gave in, on the condition that my cousin - who worked in my Dad’s store - and not my Dad would accompany me.

Harbhajan Singh - Bhajan for short, ‘Bhajan Veer ji’ to me - was designated my escort and guardian for the evening.

Bhajan was not happy. Yes, he wanted to see Dara Singh as much as I did, but not with a pesky cousin tailing along.

We had had an unfortunate incident only a few months earlier.

The much-heralded, much acclaimed film, Nagin (The Cobra), had finally arrived in Patna after a whirlwind of hoopla. People lined up to get tickets for days. My parents had no interest in it. So, Bhajan got to take me because I wanted to go!

I was 5 years old.

Bhajan dutifully used all of his connections until he managed to finagle two tickets. Excited beyond words, we sat in our seats, eyes glued to the screen, as Pradeep Kumar began to play the been (a wind-instrument used by snake-charmers, its sound remotely similar to a bag-pipe’s), Vijayantimala began to gyrate … and, as was the intent, cobras appeared as well, swaying and dancing, intoxicated by the music.

I tugged on Bhajan’s sleeve.

“I want to go home,” I said.

“W-H-A-T!” he shouted, as close to a whisper as he humanly could.

I did not like snakes, and I wanted to go N-O-W.

How do you argue with a 5-year old? Especially one terrified by snakes, and dozens of them slithering on the huge screen.

Bhajan had to take me home, mere minutes after the film had begun.

Suffice it to say, he never forgave me for that night. It took him months before he could finally get to see Nagin, and he blamed it squarely on me.

So, here we were, less than a year later, together, heading for the Kala Manch (Theatre of the Arts), a ramshackle arena earmarked for the night’s wrestling tournament, the crowning finale of which would be: the Winner vs. Dara Singh.

No love flowed between the two of us as we headed out on a rickshaw, but it didn’t matter to me: I was going to see Dara Singh! Live!

I had been to Kala Manch once before. The famous Punjabi actor Prithvi Raj Kapoor (father of Raj, Shammi and Shashi) had brought a play to town, depicting the recent horrors of the Partition of Punjab. I remembered the evening well: at the conclusion of the play, Prithvi Raj had come down into the audience, his arms out-stretched with a shawl draped over them, begging for donations to help the refugees who were still in camps in Punjab.

The evening was seared onto my memory - it was a cash society then, no cheques, no credit cards! - and people, all teary-eyed, had spontaneously opened their hearts and emptied their pockets, with the women throwing their gold jewelery into his arms.

I thought the whole scene had been mighty strange, but my father had explained why, while my mother had sat, red-eyed and mouth smothered with her chunni.

This evening, though, was going to be different.

To begin with, the monsoons were in full swing and it felt like we were standing at the foot of Niagara. I remember each moment of the evening in great detail: after all, it was Dara Singh I was going to see!

The chaos outside to get in - the queue had not been introduced to India by the British, as it still hasn’t since by the desis - was memorable. There were thousands outside, and each wanted to get in FIRST and NOW!

Once inside, there were new adventures that awaited us. The tin roof of the Kala Manch was no match for the monsoon. Water was leaking everywhere. Which meant that the seating arrangements weren’t going to work. There were no rows left. In fact, no seats were visible on the floor. People were either standing on them, or holding them over their heads as umbrellas. Wall to wall. The organizers, taking advantage of the added space thus created, kept on selling tickets and letting people in, until it was a mass of standing humanity.

Bhajan had no choice. I sat on his shoulders, with the best view in the house.

Odd, but there were no other kids in the house.

Hours passed by, with occasional word that the event may have to be cancelled, because of the rain. Succeeded by varying rumours: the wrestlers have arrived, and are on the way. They’re refusing to fight in the rain. They’ll come but they won’t fight. They’re not coming. Yes, they are …

Late into the night, close to midnight, when the rain had relented, it finally began.

The rest is a bit of a haze for me. It was dark. It was dripping everywhere. It was past my bed-time … and this time, no matter what, Bhajan wasn’t going home early. Neither did I want to, as long as he could keep me upright on his shoulders.

The tournament went on and on and on. There were many champions, many were vanquished. Most of the stars, I noted, were Singhs … all from Punjab. There were occasional interludes … with dwarves. Which I remember relishing a lot.

And then, and then … there was Dara Singh.

He appeared and stood there at the edge of the stage, cocked and crouching with his trade-mark outstretched arms, and the crowd roared. Suddenly, the wet didn’t matter any more, nor the jostling mob, nor the overwhelming odour of sweat and smoke.

He swung around and in a single bounce climbed into the ring.

There was no music. No commentary. The sound system, if any, had long given up to the downpour. Who won? Who is it, who is it? Who’s winning? Who’s down? - were the most common yells heard around us.

We could see only shadows as they coiled and uncoiled in the ring, throwing themselves at each other, or catapulting each other all over the ring. Sometimes outside the ring.

It was magical.

I cheered and bounced non-stop. I don’t think Bhajan saw or heard anything. He just stood there, poor man, and bore his cross like a man.

I remember we all went berserk when we finally saw Dara Singh, a lone herculean figure left in the ring, with both his arms held high in timeless triumph. He had once again vanquished them all.

I don’t think I’ve seen another wrestling match since, live or on television. Nor have I ever seen Dara Singh on the screen - he became a lead film-actor a decade later and found new levels of adulation.

But I remember that night in Kala Manch as if it was yesterday.

Bhajan? I don’t think much love was lost between us that night or since. It’s been a life-long regret, though, that I never got a chance, when I grew up, to thank him for all his trials and tribulations. It’s too late now - the dear man passed away a few years ago.

Dara Singh? Now 83, after several decades of a successful career as a movie actor and producer, is in hospital, in a life-and-death struggle. Judging from the e-mails I have received these last few days from the world over, there’s a billion people thinking and praying for him today.

Conversation about this article

1: Kunal Kalra (India), July 11, 2012, 10:36 AM.

Hope he gets well soon! Praying for his good health!

2: R. Singh (Canada), July 11, 2012, 11:18 AM.

Heartfelt good wishes and prayers for a speedy recovery for this great stalwart!

3: Gurmeet Kaur (Atlanta, Georgia, USA), July 11, 2012, 3:14 PM.

I am so touched by this story - but the person that moistened my eyes is your Bhajan Veer.

4: Ari Singh (Burgas, Sofia), July 11, 2012, 3:42 PM.

I wish Dara Singh good health. I saw him in Kenya in those days along with his brother, Sardara Singh. In my opinion, he is the only true Bollywood hero! I have been his fan since then. I pray for his health.

5: Kabir Singh (New York, USA), July 11, 2012, 7:54 PM.

A touching story. Let's hope for the good health of Dara Singh. In my personal opinion, the real hero in this story was not Dara Singh but your cousin, Bhajan Veer ji.

6: Shivdas More (Pune, Maharastra, India), July 12, 2012, 3:45 AM.

Dara Singh ji - who inspired us all as the ultimate Strong Man, the "Mard"!