Columnists

The Sikhs In Britain

A Book Review by RAVINDER SINGH

THE FOLLOWING BOOK HAS BEEN SELECTED sikhchic.com's BOOK OF THE MONTH FOR DECEMBER 2011.

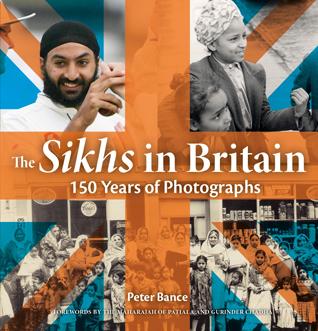

THE SIKHS IN BRITAIN: 150 YEARS OF PHOTOGRAPHS, by Peter (Bhupinder Singh) Bance, Coronet House, London, 2012. New Edition, Hardcover, B & W and Colour illustrations, pp 186, 22.99 Pounds. ISBN: 978-0-956-1270-2-0.

The adage, “a picture is worth a thousand words,” very aptly describes Peter (Bhupinder Singh) Bance’s, The Sikhs in Britain: 150 Years of Photographs.

First published in 2007 and now in its revised version and second printing, the book is a visual celebration and stunning

photo essay of Sikhs in Britain - from the arrival of the first permanent Sikh resident, Maharaja Duleep Singh in 1854 to the present-day Maharaja of the Marathon, the centenarian Fauja Singh.

Between these two milestones are 150 years of photographs and illustrations, many from private collections and never seen before, that capture the many faces and reflections of Sikh life in Britain.

It makes for a fascinating journey.

It is designed to be a coffee table book - and it is quite exquisite indeed. But unlike any other, it offers more than just a visual treat.

Coffee table books like The Sikhs in Britain, unlike their library or bookshelf counterparts, are often thought of as no more than an adornment, an object of art and decoration, to be seen but not read.

Peter Bance breaks that mold.

The front cover is an imaginative juxtaposition of pictures of Sikhs over an image of the Union Jack. The choice of the first two pictures in the book complement the cover and caught my attention.

The first picture, c1936, constituting the frontispiece, shows four Sikhs, fashionably dressed like English gentlemen - complete with three-piece suit, leather shoes and umbrellas - standing outside an underground (subway) station. But, instead of bowler hats, all four are sporting beautifully wrapped turbans and beards!

The second picture shows Birmingham-born 28-year-old Chaz Singh, posing as St. George in Plymouth, in 2008. The caption describes Chaz as Plymouth’s first Sikh Councillor and an activist who has made a public statement (through images and

campaigns) about his Sikh identity: Made in Britain!

The message is clear: being British and being Sikh are not mutually exclusive.

The book consists of nine chapters, an introduction, a long list of obligatory acknowledgements and a foreword - two, in this case, one by the Maharaja of Patiala and the other by the film maker, Gurinder Chadha. A time line, a glossary and even a

bibliography round out the 186-page volume.

Sikhs in Britain are a thriving presence. But their distinct identity and their success evokes, in certain quarters, envy, prejudice and even hostility.

The similarity with the Jews is not lost on the author. It is no accident, he states, that the first Sikh immigrants to Britain in the 1920’s followed the pattern of the Jewish community by “engaging in the peddling trade, bought their supplies from Jewish

wholesalers and resided in the Jewish East End of London.”

However, Sikhs have never “adopted a strategy of lying low, even in the face of negative reactions from their peers. Rather, they have built on this and turned it into one of their strengths. Hence their success in India and abroad.”

Chardi Kalaa at work!

The author identifies four significant “waves of Sikh migration to Britain,” starting “between the two world wars,” followed by the second, “after Indian Independence in 1947,” and the third and largest in the 1960’s, concluding with a fourth, in the 1970’s, consisting mainly of East African Sikhs.

But Sikhs had already set foot in Britain prior to the 1920’s. In less than fifty years of the signing of the Treaty of Amritsar in 1811, Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s son, Duleep Singh, was escorted off the boat at Southampton in 1854 - an unwilling child exile, a forced convert cut off from his community through a deliberate assimilation into British aristocracy.

Sikh Maharajas, especially from Patiala, Kapurthala and Jind, were also very visible in England and Europe during the late nineteenth century - though not always for the right reasons. Their images are captured in the first two chapters of the book, “Early Sikhs to Britain,” and “Visiting Royalty and Nobility.”

I wish we had a picture of Bhai Kahn Singh Nabha who visited with Max Arthur Macauliffe, the historian of the Sikhs during this period.

Some pictures from the two World Wars will ring familiar with readers as they will recognize some faces. Among others, they depict Hardit Singh Malik, Mohinder Singh Pujji and Manmohan Singh, all well-known war heroes.

Personally, I found the war pictures of ordinary Sikhs in extraordinary surroundings and situations more interesting: Ram Singh Suwali, an Air Raids Precaution worker, talking to King George VI during the Blitz of Birmingham in 1940; a WW II publicity

postcard captioned, “ A Sikh Factory Inspector,” with a picture of a Mr. K. Singh; a Sikh arms worker in Hertfordshire in 1941 and Sikh soldiers celebrating Vaisakhi in 1945 at the Bhupinder Singh Dharamsala (now better known to us as the Shepherds Bush Gurdwara).

From the 1920s to 1947 is the subject of Chapter 4. The first significant arrival and growth of Sikhs in Britain occurred during this period, largely due to the arrival of the Bhatra Sikh community from the Sialkot region of West Punjab. A close-knit group, they were itinerant traders or peddlers who went about selling household wares and clothes - door-to-door or from the equivalent of modern day American flea markets. What struck me in thumbing through the pictures in this chapter was how well dressed (by today's standards) the Sikh peddlers appear.

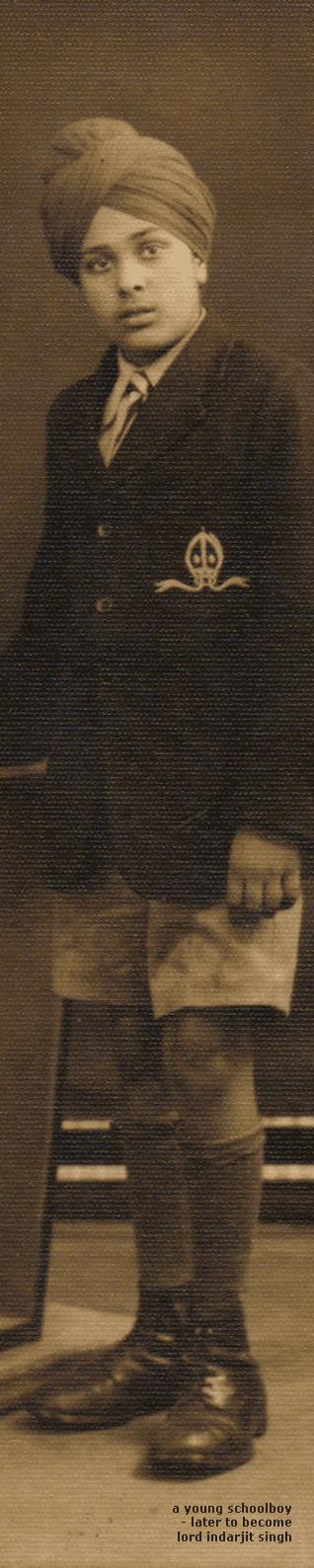

This period also witnessed the arrival of the children of the wealthy and the privileged who enrolled at schools and colleges for a proper education!

Labor shortage in a booming post-WWII British economy offered Sikhs, uprooted by the Partition of 1947, an opportunity to rebuild their lives. Chapter 5 recounts their arrival in Britain in the decade after the War. Unlike their earlier counterparts, the Bhatras, who clustered around seaports and stuck mainly to peddling, the second wave of Sikh migrants had the opportunity to find factory jobs in the cotton mills of Lancashire, the auto industry in Coventry and industrial parks in Manchester and Birmingham.

Pictures of Sikhs protesting the Partition in front of 10 Downing Street in 1947, or the Khalsa Jatha raising funds for service at the Darbar Sahib and a rare picture of the wrestler Dara Singh touring Britain, tell an interesting story - that in the midst of trying

to put down their own roots in a foreign land, Sikhs remained politically and socially active and did not lose their zest for living.

One picture that stands out for me is on page 76 and shows a young Sikh, Jaswant Singh Jas, at the Chatter Secondary School in Cambridgeshire in 1949. His Sikh spirit is captured in the caption, which tells us that as the only turbaned Sikh in the school (perhaps in the country), he had put the entire school on notice (through his teacher) that his turban was sacred and not to be touched. Or else, there would be consequences!

Evidently, one of his white friends would hold his turban as Jaswant got into a fight!

Indeed, instead of the handwringing I witness these days, this is the spirit that we should inculcate in our kids.

The 60’s brought families (wives and children) that Sikhs had left behind in India as they tried to find a footing in the new country. From shared lodgings, Sikhs began to buy homes, making a second income a necessity. Despite language and cultural barriers, women began to find employment and work alongside their men.

It would unimaginable to find a cluster of Sikhs - anywhere - with no gurdwara.

The pictures in Chapter 7 testify to the fact that Britain was no exception. From the founding of the Khalsa Jatha British Isles, c. 1908, by Teja Singh, to the acquisition of a lease for the first gurdwara on Sinclair Road in London (thanks to a handsome donation from the Maharaja of Patiala), the growth of gurdwaras followed immigration - and clan/ village/ caste patterns - a trend that has been visible in other countries as well.

No history of the Sikhs in Britain would be complete without mention, or pictures in this case, of the Sikh exodus from East Africa in the 60’s and 70’ and the fight for preservation of the Sikh identity, especially the wearing of a turban in government jobs.

The appearance of color pictures in the last chapter, titled The 80’s to The Present, reflects not just advancements in photography, but also the coming of age of a community.

Sikhs everywhere have made an impact out of proportion to their numbers. In Britain, their presence in every walk of life is reflected in these pictures: there is Prince Charles, obviously at home around Sikh-Britons; Sikh exhibits at the Victoria and Albert Museum; Lord Indarjit Singh posing with the Queen and figures like Fauja Singh and Monty Panesar.

Sikhs are rightfully proud of their past but the past, like pictures, is silent until evoked and described. We Sikhs are not much given to recording and preserving history.

Peter Bance has done just that and deserves our thanks for this exquisite labor of love.

The book can be purchased online from any of the folowing outlets:

www.amazon.co.uk

www.waterstones.com

www.coronethouse.co.uk

www.duleepsingh.com

December 1, 2011

Conversation about this article

1: Lakhvir Singh Khalsa (Nairobi, Kenya), December 01, 2011, 10:19 AM.

Kenya - the birthplace of the world's KalaSinghas (the respectful name give to Sikhs by Kenyans) ... Proud to be a Sikh-Kenyan!

2: Ranjeet (Southampton, United Kingdom), December 02, 2011, 8:16 AM.

Just a note to Ravinder Singh ji, the author of the review. The four stages of Sikh Migration to Britain was first propounded by Roger Ballard, and is commonly known as Ballard's Four Stage Migration Process (1977). Credit to Peter Bance. A brilliant and timely book.

3: Baldev Singh (Bradford, United Kingdom), December 02, 2011, 2:15 PM.

Some Sikh-Britons have just added another trend to the repertoire: a 'pointed' starched turban and trimmed beard to go with it! Not a very good advert for the Khalsa or Sikhi, I'm afraid!

4: Khalsa Lakhvir-SINGH (Nairobi, Kenya), December 03, 2011, 4:32 AM.

The starched turban was a Kenyan style which I am glad to say has largely diminished here in the past decade or so. More and more of Sikh-Kenyans are now tying their turbans daily and have dome away with the 'hat' (starched turban). I think the starched turban is still a trend in the United Kingdom because the community there is larger and for them life is on the fast track and the starch turban is just a shortcut to trying to remain relevant in the midst of Sikh pride.

5: Raj Hundal (London, United Kingdom), December 15, 2011, 5:14 AM.

As a photographer myself, I found this book visually pleasing. As a Sikh-Briton, I think this book has great value to anyone interested in history, journeys and struggles of our parents and grandparents. I'm glad I bought it and would highly recommend it.

6: Rachel Burton (England), April 24, 2012, 1:03 PM.

I think it is a good website apart from it doesn't actually explain everything ...