Images below: First (and Thumbnail) - Guru Gobind Singh, Mata Sahib Kaur and the Panj Piare. Second - the Massacre at Jallianwala Bagh, Amritsar. Third - The Guru ka Bagh Morcha. Home Page - The British surrender the Durbar Sahib keys.

Vaisakhi

Jallianwala

Bagh

Guru

ka

Bagh

Art

Images of Freedom

A book review by MANJYOT KAUR

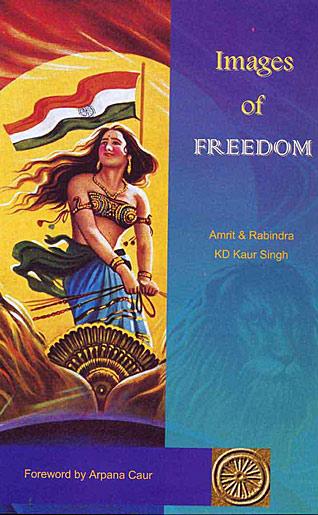

IMAGES OF FREEDOM, by Amrit and Rabindra KD Kaur Singh. Indialog Publications Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi, 2003. ISBN 81-87981-35-0. 128 pages.

The Singh Twins, as British-born and based identical sisters Amrit and Rabindra Kaur Singh are familiarly known, are internationally-renowned artists whose vision of popular culture, society, media and politics reinterprets a wide range of traditional art forms as embodied in historical paintings.

In addition to their dual career as artists, they jointly write, curate exhibitions, and lecture on various aspects of Sikh, Indian and British art and culture.

In this book, the Singh Twins examine the phenomenon of popular printed images - or "calendar art", as it is often generically called - pertaining to the pivotal historical period of the Indian Independence Movement. As they explicitly state, they did not intend their work to be an in-depth or scholarly look at India's Freedom Struggle.

Rather, its aim is to explore how this potent art form provided a means of expression (not only during the 1930s, 40s and 50s, but also in more recent times) for Indian popular sentiment regarding this significant era.

Most of the fifty images in this book, chosen from the private archives of Amrit and Rabindra Kaur Singh, come from a large set of stock samples used in catalogues publicizing the products of one of North India's earliest picture publishers, Hem Chander Bhargava. The remaining illustrations were taken from a collection comprising a variety of printed formats: greeting cards, calendars, company advertisements, posters, key rings, badges, and the like.

Their mass production ensured they were accessible and affordable to all, making them a truly popular form of art that accurately mirrored India's evolving religious, political, and cultural mores.

As the Singh Twins cogently explain in their excellent Introduction, India's Independence Movement was regarded not only as a continuation of its historical struggle against foreign invasion, but also in a more philosophical context, as nothing less than part of humanity's eternal battle between Good and Evil.

The authors effectively describe how, in projecting popular sentiment as it was inspired by historical role models and traditional religious iconography, the printing and publishing industry realized the awesome might of visual imagery in mass communication, and transformed it into "a powerful propaganda tool in terms of uniting Indians in a common cause for freedom and promoting the post-Independence vision for Free India".

Through their various works, the artists these companies employed strove to "create a new sense of national identity and vision of Indianness that would re-kindle the self-pride and confidence India needed to unite her against the common 'enemy' of the Raj".

These themes are also discussed in a well-written Foreword by contemporary artist Arpana Caur. She stresses that, in spite of the depth to which high-tech, computer-generated media have penetrated our contemporary lives, the freshness and directness of less-sophisticated popular imagery - such as "calendar art", with its bold colors and simplified rendition of figures - have retained a great appeal.

According to Caur, this art form bears "the fragrance of a lost innocence" from a time when "all religious barriers disappeared before one glorious goal: Freedom". She feels that today's India, plagued by increasing religious and cultural intolerance, as well as power-hungry politicians, has forgotten this "greater goal".

Hence, it has become "nostalgic for that time when Bhagat Singh, Udham Singh and Gandhi, all were thinking only of one thing", with images of the "dreamers and martyrs" who made a free India possible, taking on a renewed and urgent sense of relevance.

A "List of Plates" follows these two preliminary sections.

In each of the five segments which form the main body of Images of Freedom, a range of helpful data is provided for every illustration shown: its size, date, artist, source, the language of its inscriptions, and any company marks it bears. A detailed description of the image is given on the facing page, which greatly helps to situate, in the contexts of place and time, the people and events it depicts.

Another illuminating feature of the authors' explanation is that it masterfully "connects the dots", linking the techniques used in the piece to those employed in traditional styles of Indian art, such as murals and miniature paintings.

It should be noted that, for the purpose of this review, I will focus on only the book's sixteen Sikh-related pictures and explore their part in both the development of the art form under study, and to some degree, the contribution of the Sikhs and their extraordinary and disproportionately high role in the independence struggle.

Regarded as the first great martyr of the Sikh faith, Guru Arjan, the fifth Sikh preceptor, set a timeless example of the nature of self-sacrifice and serenity in the face of oppression that would continue to be expected from later "freedom fighters for the sake of Mother India". As seen in the time-honored Indian folk art of scroll painting, the entire cycle of events relating to his martyrdom is shown, in distinct yet interconnected vignettes.

A small inset, showing a section of a wall in Amritsar's Gurdwara Baba Atal, connects this juxtaposed style to that of traditional Punjabi murals.

In a similar way, the martyrdom of Guru Tegh Bahadur, known as "Hind Ki Chaddar" ("Shield of India"), was used by political leaders of the Independence Movement to inculcate the spirit of sacrifice and endurance called for in the struggle for freedom. Made in the 1930s, this depiction of the saintly ninth Guru and the Hindu Brahmins pleading for his intercession, shows the flattened "theatre style" backdrop characteristic of popular imagery of that decade.

Four images are given of the Tenth Master, Guru Gobind Singh, heralded by many involved in the fight for independence as the ultimate role model, his eternal values of sacrifice, equality and unity inspiring all the generations to come.

A pair of them show elements of both Indian and European styles of art, combining classic postures of Indian courtly miniatures with elements of Western artistic realism.

In the other two, he is portrayed initiating the Panj Piare into the newborn Khalsa, an act which symbolized the communal hope that, just as the Khalsa brought about the fall of the mighty Mughal Empire, so, too, would the new wave of Indian nationalism succeed in driving the British rulers from Indian soil.

A portrait of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, shown with Sardar Hari Singh Nalua, recalls those of the Sikh courtly miniatures of the early to mid-19th century. Founder of the first Sikh kingdom in the Punjab, Ranjit Singh's ending of two hundred years of foreign domination in that region made him a great national hero at the time of Indian Independence.

The two men are surrounded by various types of weaponry, including pistols: a most anachronistic touch of artistic license. It was painted by G.S. Sohan Singh, one of the most prolific producers of popular Sikh imagery.

The extraordinary might and bravery of Baba Deep Singh made him one of Sikhi's most revered martyrs. This image is inset with a depiction of the shrine at Amritsar erected in his honor, indicating its function as a souvenir poster produced for sale to pilgrims. Although Baba Deep Singh is shown in the classic posture of Sikh mural tradition, the glossiness of this brightly-toned 1991 reproduction reflects the technological advancements achieved by India's modern-day mass-art industry.

Another legendary Sikh martyr, Bhagat Singh, occupies a prominent place in five group images portraying national heroes of a more contemporary era. Depicted in the famous Westernized disguise he is known to have used while evading British authorities - a fedora hat, rakishly topping his short hair - he is shown in several valiant poses, along with a variety of noted personages ranging from the 17th-century warrior, Shivaji, to a leader of the Congress Party, Subhas Chandra Bose.

A particularly dramatic one is quite reminiscent of Christian "Sacred Heart" imagery: he has torn open his chest to reveal Mother India (who bears the Congress Party's spinning wheel emblem and the national flag).

In his last depiction, he is shown as having reverted to his full Sikh identity - which he did after he was captured - complete with unshorn hair and beard, he is shown with the saintly leader, Bhai Randhir Singh (with whom he is reported to have met at length during his final imprisonment), as well as his (Bhagat Singh's) two close political associates, Sukhdev and Rajguru, along with whom he was hanged by the British in 1931.

A scene from the Jallianwala Bagh massacre of 1919, where British infantry fired upon thousands of Punjabis gathered in the eponymous park for a Vaisakhi celebration, from the brush of Gurdit Singh, is excerpted from a 1997 calendar, published by Delhi's Sikh Gurdwara Management Committee to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of Indian independence.

As the authors explain, the patronage of popular imagery by Sikh religious institutions developed independently of the mainstream mass-picture industry. Unlike typical "calendar art", these images were distributed free of charge, with a view towards educational and public relations outreach to the wider Indian and Western communities.

This infamous incident was followed by the Morcha Guru Ka Bagh of 1922, when thousands of Akali (not related to the current political party sharing the same name) Sikhs non-violently protested being denied access to this Amritsar-area shrine.

Published in a calendar commissioned by the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee in 1984, this dramatic image was painted by Kirpal Singh, the artist behind the creation of Central Sikh Museum in the Golden Temple complex in the 1960s.

His graphic representations of acts of bravery, patriotism and martyrdom captured the imagination and stirred the hearts of the entire Sikh community. According to the authors, he is credited with being the father of popular Sikh art, having created "an archtypal vision of collective Sikh consciousness and identity".

The last Sikh-related image in the book is a depiction of the 1922 "Keys Affair". Through a series of peaceful protests (in which many were killed by British authorities), Sikhs regained their rightful control of the Harmandar Sahib from the British.

This illustration shows the British Deputy Commissioner personally delivering the keys of the Harmandar's toshakhana (treasury) to the then Sikh leader who led the "Gurdwara Reform Movement" protests, namely, Baba Kharak Singh.

Like the previous two examples of "officially" commissioned imagery, this 1997 calendar painting by Gurdit Singh focuses sharply on the Sikh historical context, using insets (here, by the contemporary calendar artist, Amolak Singh) to highlight key participants in the event being depicted.

Brief, but highly informative, biographies of the artists, as well as two pages of "Resources" and "Explanatory Notes", capably conclude this work.

For those readers who are already acquainted with the artwork created by the Singh Twins themselves, this book will strike some very familiar chords. Visually, it is a sumptuous and satisfying feast. The reproductions of the paintings are uniformly of high quality. Obvious care was taken in the composition and layout of its pages; the authors' keen passion for complex decorative touches and meticulous attention to even the smallest of details are everywhere apparent. Names, places and events are explained in the text with clarity and precision.

Commensurate with my own interests, I must admit I would have liked to have seen a greater proportion of the illustrations devoted to Sikh-related images. However, the authors can in no way be held responsible for this. As they note in their Introduction, the artwork represented in the book thematically reflects the ratio that existed in the collection as a whole.

It also would have been wonderful to see women included to a greater degree in these images. Except for the presence of Mata Sahib Kaur in one of the illustrations of Guru Gobind Singh initiating the Panj Piare, they are notably absent. They surely suffered and fought for freedom as much as their male counterparts.

But, I feel it is safe to assume this also is not attributable to a decision made by the authors. If these types of depictions had appeared in the collection or in the popular art form under study, I believe they surely would have been added to their selection.

My own bents and biases firmly set aside, it would indeed be difficult to find fault with this book. It is highly informative, without the slightest hint of a dry and textbook-like tone. It marks the events which changed the course of history and celebrates pride in Sikh and Indian identity in quite an inspirational manner.

Adroitly connecting the past with the present, it spurs the reader with the urgent need to remember - and to learn. As Arpana Caur fervently wishes in her Foreword: "Hopefully, there is still time ..."

[For more on the art and other works of The Singh Twins: http://www.singhtwins.co.uk/. The book, Images of Freedom, can be ordered from fineart@singhtwins.co.uk at 10 UK Pounds each.]

All illustrations shown here are details from calendars in 'The Twin Studio Sikh Print Archive'.

Conversation about this article

1: Manjeet Singh (Brampton, Ontario), August 17, 2007, 10:49 PM.

India's Day of Independence is the Sikh Nation's Day of Enslavement.

2: R. Sandhu (Brampton, Canada), August 22, 2007, 1:01 AM.

Why are the panj pyaras and Guru Sahib shown in saffron? Whatever happened to the blue robes? [Editor: they've always been depicted in saffron, in recent memory. The use of blue for these purposes has, until recently, been limited to the nihangs and has surfaced only recently as the colour of choice by some fringe groups. More importantly, our Gurus had freed us from being married to "holy" or "pious" colours - none of them have religious significance.]

3: R. Sandhu (Brampton, Canada), August 22, 2007, 3:35 PM.

It is worth noting the dress of the Nihangs/Akalis (now they mean different things!) of the Ranjit Singh era. Was there a time when the Akalis displayed a greater glory - besides the Jaito/Guru-ka-bagh morcha? Now we have only fringe groups left to display this piece of history? That is rather sad, and hardly inspirational!

4: Zeeshan (Hyderabad, India), August 15, 2008, 10:45 PM.

Excellent.

5: Vivek Bhartal (Ahmednagar, Maharashtra, India), March 21, 2012, 10:38 AM.

Very good composition and colour scheme.