Books

Another Look At "The English Patient":

The Book & The Film

by NIKKI GUNINDER KAUR SINGH

THE ENGLISH PATIENT, by Michael Ondaatje (1992) has been selected sikhchic.com's Book of the Month for December 2010. Eighteen years after it was first published, and fourteen years after it was turned into a movie, it is time to take a fresh look at the two versions ... through the eyes of a brilliant scholar.

"One of the things that surprised me with this book was the arrival of Kirpal Singh. I suppose, subconsciously, it was just waiting to happen, but it came as a complete surprise. Kirpal Singh is a soldier with the Royal Engineers who's been traveling through Italy defusing the bombs left by the Germans. There's a pivotal scene in the book in which Hana is at her lowest - almost suicidal, though it is just hinted at. She starts playing the piano in the villa, and at that point two soldiers walk into the room. It was such a surprise to me, as a writer. I thought, Wait a minute! What's happening here?

"No one believes that I wasn't expecting them. But it was a moment. I thought, okay, I've got these two other people in the room, and then I had to wait to see what would happen. I started to investigate Kirpal Singh, trying to find out who this person was, what his job was. And that became, in a way, a new part of the book, a new character whose presence fills one-quarter of the novel." [Michael Ondaatje, in an interview with Eleanor Wachtel on CBC]

For the reader as well, Kirpal Singh's appearance in The English Patient comes across as a surprise, in fact as a wonderful surprise. It is so seldom that post-colonial literature has Sikh protagonists, and if and when they are, the Sikhs are blasting bombs - not defusing them. But here we have, according to Ondaatje himself, one-quarter of The English Patient devoted to the development of a Sikh. And even more importantly than the space given to Kirpal Singh (Kip) is the inspiration that comes from him, and the effect he has on the other characters.

Ondaatje's verbal camera focusses on Kip's appearance, on his upbringing in Punjab, on his sacred space - The Golden Temple in Amritsar - and on his spiritual-psychological development from a colonial to a postcolonial character. The more authentic Kip becomes as a human being, the more deeply rooted he becomes in his own religious faith. Ondaatje's narrative serves as a beautiful introduction to Kirpal's Sikh identity.

Such an introduction is desperately needed in our dangerously divided and polarized world. Since September 11, several hundred Sikhs have been victims of hate crimes in America. In the mind of the attackers, Punjabi Sikhs are the same as Afghani Muslims and Afghani Muslims are the same as al-Qaeda terrorists. In Phoenix, Arizona, a Sikh gas station owner was murdered in that blinding rage. It is urgent that we in the West learn about our Asian neighbors and begin to respect them.

Ondaatje provided Miramax with a wonderful opportunity to familiarize Western audiences with some fundamental aspects of Sikh physical identity and spirituality.

Unfortunately, however, the film reduces Kip's profound personality into a one-dimensional representation. This duplicitous phenomenon is carefully explained by Jackie Byars: "Representation is not reflection but rather an active process of selecting and presenting, of structuring and shaping, of making things mean".

It took the director, Anthony Minghella, three years to develop the kind of script that producer Saul Zaentz could sell to a studio. In his press notes, Minghella admitted to "sins of omission and commission". Minghella is undoubtedly a brilliant and creative director, but the economic profits from western moviegoers dominated his vision, and through brainstorming sessions with Zaentz, Minghella worked strenuously for those three years to produce a triumphant success - winning numerous Oscars, including the Best Film Award for 1996.

But as far as Kip is concerned, the film fails terribly. Moviegoers neither get to meet Ondaatje's authentic Sikh character, nor do they learn about his Sikh heritage. Alas, Minghella's film fails to replicate Ondaatje's great contribution to religious pluralism. This film still leaves us ignorant of our "brown" neighbors. So in spite of their presence for over a century in America, Sikhs with turbans are often mistaken as al-Qaeda members and are target of hate crimes.

In the film Kip's turban , the emblem of Sikh pride, is carelessly tied. Its shabby appearance on the Hollywood screen recalls the term "raghead" which is what the first Sikh immigrants were called in America. Ironically, the subject who frees himself of British colonialism in Ondaatje's novel becomes in the film an object of American racial and sexual obsessions. He is the ideal case of one who is twice repressed. Edward Said's theory of Orientalism is very effective for analyzing Kip's cinematic reproduction. In Said's popular words,

Orientalism was ultimately a political vision of reality whose structure promoted the difference between the familiar (Europe, the West, "us") and the strange (the Orient, the East, "them"). This vision in a sense created and then served the two worlds thus conceived. Orientals lived in their world, "we" lived in ours. The vision and material reality propped each other up, kept each other going. A certain freedom of intercourse was always the Westerner's privilege; because his was the stronger culture, he could penetrate, he could wrestle with, he could give shape and meaning to the great Asiatic mystery.

The binary opposition between 'them" and "us" which Edward Said made us so conscious about years ago, infects the 1996 Miramax production. Even though Ondaatje's Punjabi sapper comes to Europe during World War II, and warmly embraces Catholic frescoes in Italy, the Canadian Hana, the Hungarian Almasy, and the Italian thief, Minghella and his crew reshape him and recast him in a very different meaning - as Said would say, in "one of its deepest and most recurring images of the Other."

Said's theoretical framework offers us valuable insights into examining the colonialist master discourse of Hollywood, especially, how Hollywood dominates and restructures the Sikh protagonist through a sumptuous display of Oriental stereotypes, images, and fantasies.

The Displaced Other

... the Orient is all absence, whereas one feels the Orientalist and what he says as presence; yet we must not forget that the Orientalist's presence is enabled by the Orient's effective absence. [Said]

Kip's place before or after post war Italy has no relevance for Hollywood, for both his migration to England which precedes his bomb-diffusing in Italy and his return to Punjab, are conspicuously erased in the film. By erasing the spaces where Kip grows up socially, culturally, and religiously Hollywood not only dislodges Ondaatje's hero to the periphery but also makes him a momentary and insubstantial figure. As Homi Bhabha remarks in "The Other Question ... " it is through phantasy that the colonist desires and defends his position of mastery. Without history and identity, the Sikh sapper effortlessly glides in and out of Hollywood's phantasy world.

Not only is Kip's historicity but even his mental journeys home to the Punjab during his stay in the Villa are entirely absent from the screen. Memory and imagination superimpose as Kip and Hana travel together during those verbal nights to the central shrine of the Sikhs, their Harmandar in Punjab. Ondaatje presents a most beautiful and sensuous experience of the Sikh shrine. We see the structure of the shrine inlaid with gold and marble lifted by the shimmering waters surrounding it. How easy and splendid it would have been to flash an image of the Harmandar - even for a second!

But the film utterly omits this sublime vision, and thereby categorically conceals Ondaatje's pluralistic perspective in which the Sikh shrine is linked with the Desert and with the Villa Girolamo. These are three important spiritual locales which nurture and bring out the best of humanity. Great religious figures like Moses, John the Baptist, Christ, the Desert Fathers, Prophet Muhammad were all attracted to the Desert. It was in that open and limitless space and silence of the shimmering sand that they carried on their communication with the Divine. Ondaatje's early-twentieth century explorers in the desert also acknowledge the presence of the Divine in their midst.

Whereas the world outside is sunk in economic and political wars, everyone fighting to shape and fashion matter and materials after their own name and profession, people in the desert renounce all their artificial hierarchies and possessions, and became a part of the infinite space. It is the desert that makes them truly human, "their best selves."

Just as the desert has no walls, Guru Arjan, the Fifth Guru, consciously had the four walls of the first Sikh shrine broken into four doorways as an architectural statement to welcome all four castes. The spiritual expansion of the desert is experienced in the Harmandar. As we walk barefooted beside the pool with Kip and Hana, we too smell pomegranates and oranges from the temple garden, while hearing the scriptural recitations. The harmony of the sights and sounds and smells and touch fills up all fissures and cracks, strengthening the individual. Though thousands of miles away, by envisioning his very special space in this intense way, the disintegrated senses of Kip begin to reassemble.

The Desert and the Harmandar resonate in the Villa San Girolamo. This Italian building, once a convent, is both exposed and enclosed - many of its shelled walls and doors from the war open into landscape. Our four charred victims (psychologically, and even physically as in the case of the English patient), find shelter in the villa. The fragmented architecture of the villa expresses their selves, and its open-cum-closeness, the secrets they begin to share with each other. The war breaks their walls too, and just as the rooms of the villa open up to the sky and gardens, their secrets and emotions reach out to one another. As the days pass, their wounds begin to heal.

The Harmandar, the Saharan Desert, and the Italian Villa thus provide an entry into the deepest recesses of the Self. Each serves as a vital space for spiritual and emotional sustenance. The diverse places direct us to the universal Centre, and their connection reveals the essential unity of us humans, across centuries and across cultures. But since the orientalist worldview of Hollywood is ontologically and epistemologically grounded on the contrast and difference between the West and the East, it cannot and must not disclose any links.

Kip's sacred space of course gets deleted from the Hollywood screen, but even the Desert does not come across as a place where we would find mystics and prophets. The novel's focus on Kip and his tender relationship with Hana in the Villa shifts to Almasy and his illicit passion in the Desert for the dazzling newly-wed Katharine Clifton. There are magical shots in the desert.

Through John Seale's brilliant cinematography, the body becomes fused with the topography; the sand is sumptuously transferred into silky sheets, full of sexual innuendoes. Visual pleasure is at its zenith. But as we see the wealthy and beautiful Katharine erotically gazed at and possessed by the English patient, we observe clear instances of scopophilia and fetishism (which are also repeated in the case of Kip). The White Male is in the active and dominant role, the woman, his passive other. The mystical search for Truth and Subjectivity in the Desert is clearly replaced by objectification of the "other".

In a telling scene, Ondaatje gave us a glimpse of the horrific reality of the White Man's "relief" in the Desert as he carries on his burdensome explorations. Through a mirror tacked up high in a European's tent in the desert, the reader sees a small dog-like lump on his bed - which in fact is a small Arab girl tied up both literally and imaginatively by the Orientalist. But this tragic victimization of the "other" by one of Almasy's European friends has no place in the sensual and ravishing cinematography of the Desert. Rather than face up to the tragic fact of the dog-like lump, the audience is induced to the fetishistic pleasures of Katharine's blemishless and perfect face, arms, back, and legs as they are luxuriously shot against the glossy sands.

The manipulative Hollywood camera continues to take us away from the harsh realities of Western exploitation in North Africa to cheery Christmas celebrations with a perspiring Santa giving out gifts. It brings us to exotic Cairo bazaars teeming with curious native sounds and enchanting calls from the mosque.

The media Mogul, Anthony Minghella, controls our visual pleasure in a powerful way. He and his associate "mind managers" must be very aware of the fact that western moviegoers were unlikely to identify with a brown native from India. Now Shohat and Stam have a valid argument against the notion "of any racially or culturally or even ideologically circumscribed essential spectator - the White spectator, the Black spectator, the Latino/a spectator, the resistant spectator".

Depending on gender, race, sexual preference, region, class, and age, each spectator is involved in multiple identities and identifications, ending up, as Ella Showhat and Robert Stam correctly claim, in "multiform, fissured, and even schizophrenic" positions. But in spite of the fact that there is no absolute Platonic spectatorial positioning, Hollywood does cater to a specific spectator, and that happens to be a White Male. It is therefore no accident that Kirpal Singh is out of the picture. The audience follows the European Count Almasy as the camera follows him and his gaze on the beautiful Katherine.

The Brown and the Childish Other

The Orient at large, therefore vacillates between the West's contempt for what is familiar and its shivers of delight in - or fear of - novelty. [Said]

We first see Kip lying on the ground, clearing land mines with his dark sensual hands. This scene is not from the book but the topical issue made fashionable with Princess Diana must have caught the fancy of Hollywood. Through its own additions and subtractions, then, Hollywood solipsizes the Sikh for the exoticist's pleasure: he is the dark, mysterious, feminine, and childish Other. The camera captures Kip's body, his mystery, his sexuality; it exoticizes his "oriental" body and coloring and features. We find a critical discursive strategy of imperial discourse in operation: the Asian Kip is stereotyped by Hollywood to reinforce the Whiteness, rationality, masculinity, and adulthood of the West.

In this ideological construction of Otherness, Kip's complexion forms an immediate signifier of cultural and racial difference. The camera gently turns and returns to his dark skin, according to Homi Bhabha, "the most visible of fetishes". Bhabha qualifies darkness as "a prime signifier of the body and its social and cultural correlates." Drawing upon the work of Karl Adams, Bhabha reflects upon its scopopholic value: "The pleasure-value of darkness lies in a withdrawal in order to know nothing of the external world."

Kip's brown complexion serves as an enchanting entry into a primal and mythical world. For a stressed but affluent and technologically advanced Western society, the pleasure in seeing a dark person, without being seen of course, serves as an idyllic return to Eliade's Illo Tempore, or, as Bhabha would say, "a desire to return to the fullness of the mother, a desire for an unbroken and undifferentiated line of vision and origin."

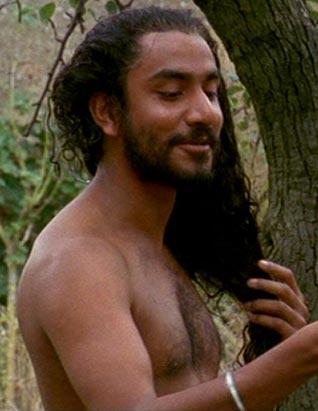

Like his brown skin, Kip's hair is also exoticized. His long hair is a symbol of his religious identity, for the kesh or the unshorn hair, is observed by Sikhs as one of their Five Articles of Faith (the "Five K's").

But rather than mark his Sikh identity, the long dark hair is fetishised in the movie. Such a representation facilitates the division between the viewing subject and the viewed object, and converts a religious person into a knick-knack for sexual gratification. With his hair on display, the Asian is no more than an interesting spectacle, and each time his hair is shown, his upper part of the body is also bare. The way in which the camera operates is subtle because it makes Kip an object of double desire. On the one hand, Hana is fascinated by the Sikh man. She gazes at him washing his hair from the English patient's room upstairs. She then runs down to give him the olive oil (an action again missing from the book) and watches him seductively from close.

Simultaneously, however, Kip is feminized for the general audience. His masculinity is neuteralized by the camera, and instead, the exoticization, the feminization of the East, gets curled up in his long, dark and mysterious tresses clinging to his bare bronze back. In fact, the depiction of his hair is so like that of Katherine's body parts. Kip and Katherine become fitting illustrations for Mulvey's Freudian analysis of Scopophilia and Fetishism which are two modes of taking sexual pleasure by looking at rather than being close to a desired subject. Through these two mechanisms, Hollywood succeeds in shifting the threat of the Other to a control and power over the Other.

Kip's long hair is mentioned many times in the novel as well: "During the nights, Hana "lets his hair free" and she witnesses "the gnats of electricity in his hair in the darkness of the tent." In contrast with the vacuous Hollywood imagery, Ondaatje's descriptions are imbued with an inner sensuousness and beauty. With his hair open, the masculine body of the soldier becomes for Hana an Indian goddess holding "wheat and ribbons." Male and female dualism dissolves in Hana's wholistic perception of the Sikh. The "gnats of electricity" in Kip's hair are analogous to the light-bulbs attached to the wings of the warrior angel in the damaged Church of San Giovanni. The peace, security, and vitality that come with the lighting up of the bulbs on the angel in the Church parallel Hana's emotions as she lies besides Kip with his hair charged with electricity in his dark tent. While Ondaatje traces the emergence of Hana's sexuality through Kip's long hair, and braids it with the sacred, the film merely shows us a foreign and effeminate Other, physically different from anyone Hana has ever met.

The deep friendship between Kip and the Canadian nurse is treated simply as childish and frivolous. Their short-lived affair is no more than an interesting sub-plot in the film. The scenes of Kip and Hana swinging in the church cheapens their spiritual feelings into mere fun and frolic. Ondaatje's brilliant depiction of the Sikh sapper's intimacy with the Virgin Mary is also left out from the film. With his verbal camera, Ondaatje leads our eyes to see Kip's turbaned head resting serenely on the Virgin's shoulder: "The color of his turban echoes that of the lace collar at the neck of Mary." Such moments of unity between east and west, male and female, human and divine, Sikh and Catholic, have no significance for the orientalist mindset of Hollywood.

It is sad that throughout the two and a half hour film we never get to see Kip grow up. In an earlier work, I discussed how Ondaatje sensitively portrays Kip's development from a colonial false consciousness to an authentic post-colonial Self, one that subtly mirrors the development of the ego in Lacan (Singh). In the Hollywood version though, Kip remains stuck in Lacan's Pre-Mirror Stage. We do not discern any relation between Kip and his reality, or in Lacanian terms, between his Innenwelt and the Umwelt. Like the infant (prior to six months), Kip does not go through the specular activity - "an ontological structure of the human world ..." (Lacan).

If anything, Hollywood dwarfs the Sikh's growth and holds him back in the pre-mirror stage. Till the end of the film we find Kip busy imitating his imperial masters - speaking their language, wearing their uniforms, and following their codes. He is unable to look into his inner self. In Minghella's long and captivating film, Kip acquires no understanding of his Sikh identity. The "series of absences" that the colonial ideologue Geroges Hardy posited for the "African Mind," Minghella posits for his Sikh character).

In Kip's instance, the series of absences are his memory, imagination, growth, self-awareness, and rationality. Immature, the Sikh sapper remains blind to the exploitations of his imperial masters, and remains ever compliant and friendly with them. What breaks him finally in the film is not the savage attack on the Japanese civilians by the Western civilization but the booby trap death of Hardy, his British sergeant! Hollywood's typically Orientalist representation clearly demonstrates the truth of Said's judgement: "the very possibility of development, transformation, human movement - in the deepest sense of the word - is denied the Orient and the Oriental."

The Silenced Other

The Orient was not Europe's interlocutor, but its silent Other. [Said]

As Hollywood carries forth its binary typology, Kip is muted. His crucial recognition of Western seduction and exploitation, his challenge of western hegemony, his attack on Euro-centric sensibilities, are entirely obliterated from the film.

There is, however, one scene added earlier on in the film where Kip objects to the British. We find Kip reading out the opening of Rudyard Kipling's Kim to the English patient - a striking contrast from the novel where it is Hana who reads the passage to the English patient. But Kip is reluctant to read this opening passage which describes the cannon reigning over the city of Lahore. He cannot carry on, he says, because the words "stick in my throat." It is strange that Almasy who was against nations and boundaries would be insensitive to Kip's feelings for he insists that Kip read the words slowly, "at the speed of the author's pen." Kip explains that the cannon in Lahore was made by melting down cups and bolts from every household, and he slowly reads, "later they fired the cannon at my people, comma, the natives, full-stop."

We discern Kip's hostile reaction but it is only reaction to Kipling's narrative - to a particular book, and to a particular author. In fact it seems to be motivated by Almasy's rather pedantic suggestion that he learn to read Rudyard Kipling slowly. Kip's is not a real critique of Britian and does not indicate any self-awareness on his part.

Actually, Kip's complaint does not make much sense to the audience. His character is not developed for us to empathize with his perspective. Lahore means nothing in the film. In the book Lahore has many associations. It was in Lahore that Kip's body was marked with yellow chalk - like bombs - by his British officials. Unlike the reader, the audience is not aware of the link between Kipling's fabulous narrative of the colonial city and Kip's painful memories. It is also confusing that if Kip were genuinely angry at the British, why would he be working so devotedly in their army? Why would he be sitting beside the English patient in his British uniform?

Isn't the real issue that he regards himself a proud subject of the British and is offended by Kipling's usage of the word "native"? And would a truly important matter be dismissed so lightheartedly: "What I really object to Uncle is that you are finishing all my condensed milk." Hollywood's insertion of the scene is as good as "condensed milk sandwiches ... with salt." Ironically, the manner in which Hollywood contextualizes Kip's disgruntlement with the British, the benefit of tinned milk comes out to be strikingly more important than the disadvantages of imperialism.

On the other hand, Ondaatje's finale gradually builds up to the Other questioning Us. The English Patient may be a novel produced in the West by a Dutch-Sri Lankan, but the readers look into the novel and see an Asian, a Sikh looking at the West. In lieu of weird sandwich recipes, Kip offers urgent reflections for western readers. In his Punjabi accent, he makes them examine their attitudes towards the Other. He embodies the famous Rushdie statement: "...the empire writes back to the Centre" (Ashcroft, Griffiths & Tiffin).

Ondaatje presents him as an authentic Indian voice protesting loudly and clearly against the racial superiority and technological savagery of the West. Could Hollywood hear an Easterner attack its fundamental ideology and dominance? Would Hollywood allow an Asian to critique its superior stance in any way? Since the quintessential dream factory of Western capitalism will have no dialogue or interlocution with the Third World, it has to impose silence on him. The film leaves out the whole last section, so pivotal to the novel, and the audience leaves the theatre without hearing the liberated Kirpal vent his feelings of insult and violation. It is ironic that Ondaatje's book which ends in a postcolonial consciousness is subverted and perverted into a colonial text by Minghella et al.

The explosion of Hiroshima and Nagasaki explodes Kip's construction as a loyal subject by the imperialists, and he begins to reinterpret and redefine himself. He brings out the photograph of his family, which was somewhere hidden in his tent, and looks at it. As he unwinds his ancestral affiliation and uncovers his communal memory, he realizes "His name is Kirpal Singh and he does not know what he is doing here."

It is a moment of self-definition. He is not a fractured entity, a Kip or Kipper grease or a Kipling cake; he is Kirpal Singh, reconnected with his family and with his Sikh community. Kip's body is now freed from the tight and stifling uniform, and his hands from the weight and burden of weapons. Without the oppressive imperial codes and equipment, Kip becomes receptive to his inner feelings and thoughts. It is not the sorrow of the death of his sergeant but the rage at the West's gruesome act that sets him off. While riding his Triumph, Ondaatje even shows him spitting on the goggles as though, to use Fanon's words, he were "vomiting up the white man's values."

Such scenes are deleted from the screen, and thus Ondaatje's Kip as a vital source for counter-hegemony is lost to the millions of viewers. In the book the Sikh forcefully confronts the "English" patient and volleys a barrage of accusations at him: how the British and then the Americans converted the Indians through their "missionary rules;" how he was seduced as a child by the grand customs and manners and medals of the Masters; how his brother had warned him never turn his back on Europe - the "deal makers", the "contract makers", the "map drawers" ...

The tone in which Ondaatje's fictional figure exposes Western hypocrisy bears a striking resemblance with the influential thinker of our century, Aime Cesarie. The two belong to different races (Indian and African), different countries and continents (India/Asia and West Indies/ the Americas) and are oppressed by different colonial powers (English and French), yet the two have been victims of the same system of "thingification," and so their reactions end up being identical. Of course, as Cesaire poignantly remarks, "The petty bourgeois doesn't want to hear any more. With a twitch of his ears he flicks the idea away. The idea, an annoying fly."

The Dream Factory cannot and will not deal with Kip's disclosure of the dirty deeds of the colonizing West. The camera effortlessly leaves out the empowered Kip - no more than an annoying fly - and directs our attention to the "English" man's heroism. We see Almasy boldly walking for miles, jumping off trains, selling his maps - all to keep his promise to his sweetheart. Amidst haunting music and endless sand we see in the centre of the screen an exhausted White man - a saviour - carrying a burden in his arms, the corpse of the vivacious Katherine. The movie blatantly reminds us of Said's realization that "the Orientalist's presence is enabled by the Orient's effective absence."

The unconsciously racialized nature of Hollywood's conceptual framework also leaves out Kip's final union with Hana.

Hollywood has traditionally been very awkward about interracial communication. Jun Xing informs us that the antimiscegenation laws and the restrictive Motion Picture Code which were in control from 1934 into as late as the mid-1950s had even "expressly prohibited the filming of interracial sex or marital scenes and themes (76). Our Hollywood film from the late nineties continues to exclude any meaningful human encounter between an eastern man and a western woman. Whereas Ondaatje's novel ends in a touching scene that brings Kip and Hana together, Hollywood underscores the typical division between "East is East and West is West, and the twain shall never meet."

The book ends with a physically and psychologically mature Kip who has the urge to call Hana. Surely theirs is not a "one night stand" - a frivolous affair soon forgotten as in Minghella's film, but an intimacy lodged deeply inside both. In spite of the passage of time, and in spite of their geographical and cultural distance, the Punjabi Sikh and the Canadian nurse live closely together. They mutually understand each other, for, as the glass dislodges in Canada, Kirpal Singh picks it up in the form of his daughter's fork at his home in the Punjab before it breaks and shatters on the floor.

As his finale, Ondaatje's draws us a circle. A rhythmical pattern of peace and harmony emerges on the global scene. Our post-colonial world, with its falling glass and fork - symbolic of its dangers, uncertainties, and intransigences - can in fact lead to new ventures and new relationships. Kip and Hana are residents of our international and plural society, one in which we need to live together, understand one another, value one another. Thriving on the antithesis and binarism of east and west, Hollywood cannot accept the basic human links that shatter barriers and connect us across cultures. The Asian Other is sent away on his motorbike, never again to be seen or heard.

Instead, the film ends with Hana carrying back with her the European Count's heavy volume of Herodotus's Histories in which he had added many of his new adventures and explorations. Whatever pages he loved from other books were also cut and glued in the volume, including segments from the Old Testament. But of course spectators are blind to that powerful moment in the book when Almasy "had passed his book to the sapper, and the sapper had said we have a Holy Book too."

For the Sikh his sacred book, the Guru Granth, is the centre of his life; like Almasy's Herodotus, the focal point of his experience. Ondaatje has two men of the Book across cultures and continents share a profound human experience that goes beyond words, bringing together the Greek-Hebrew and Punjabi texts, bringing together western and eastern civilizations, bringing together the pagan Herodotus, the Jewish Prophets, and the Sikh Gurus. The Orientalist Hollywood narrative fails to project such identifications and openings for the development of a human community.

We see Hana put Almasy's book into her knapsack, but sadly, the portrait of "A Sikh and His Family" that she holds in her palm is left out from the film. Ondaatje poignantly takes us down the river of memory as Hana unearths Kip's bag from his collapsed tent and reflects upon his belongings, including his family photograph and a "drawing of a saint accompanied by a musician" (most likely, Guru Nanak and his Muslim rebab player, Mardana).

Kip's past is lovingly retrieved by Hana. She puts all of his other belongings back, but the picture of the eight-year old Kip with his brother and parents is "held in her free hand." In contrast, Hollywood sends away the Asian without a memory or a trace. Only the Western text, with the added experiences of the "English" patient, is reverently carried into the New World.

The last shots of the movie fuse together two scenes, both of which underscore the power and glory of the West. Almasy courageously pilots his plane over and above the Desert, dominating the entire golden panorama. He is fulfilling his obligation, carrying Kathryn - strikingly regal even in her shroud - to her childhood English garden. On land, Hana sits in a truck - heroically carrying forth the "burden" of the White Man. We return to the plane and the aristocratic couple we saw at the beginning of the movie.

Hollywood has also drawn a circle, indeed a brilliantly tantalizing circle, nevertheless a circle that pushes out the East. In spite of Minghella's hard work for three years, his film confirms Said's claim "that systems of thought like Orientalism, discourses of power, ideological fictions - mind-forg'd manacles - are all too easily made, applied, and guarded."

[Courtesy: Journal of Religion & Film]

December 1, 2010

Conversation about this article

1: Inni Kaur (Fairfield, CT, U.S.A.), December 01, 2010, 5:56 PM.

I was hyperventilating reading this piece! It is beyond brilliant! Spoiled for life! Will want to see every film through Nikki's eyes.

2: Sangat Singh (Kuala Lumpur , Malaysia), December 01, 2010, 7:17 PM.

Since reading Nikki's brilliant piece, I was prompted to dig my old copy of the 9- Academy Award Winning CD for "another look". While scrounging for it, I also found the equally brilliant "Schindler's List" - a 7- Academy Award winning picture - to once again impart the lesson that whoever saves one life, saves the World Entire. Thank you. Nikki ji will hopefully write again.

3: Aman Kalsi (India), December 10, 2010, 9:19 AM.

Where can I buy this book? [EDITOR: You can buy it online. Or, it should be available in any reputable book store in India.]