People

My Mothers Story:

Shukar Hai, Shukar Hai

(Part Three/ Conclusion)

by SUPRIYA SINGH

PART THREE - CONCLUSION

She completed a full B.A. in 1955.

For my mother this was a hard, though enervating time. I remember only the excitement it brought into my life. My only experience of drama as a child was going to Miranda House to see my mother's students enact tragic love stories such as Sassi Punnu.

Or hearing Mummy and her students sing Heer Ranjha, also a story of doomed love.

My mother's life seemed to be full of adventures. The story I liked best was the one about Mummy saving a girl's honour when she was cycling back with her students from Kurukshetra College at about 8:30 one night. Near the bungalows at Shahjehan Road, a young girl was standing, surrounded by a large crowd of people and one or two policeman. My mother dismounted her cycle and moved the people aside and asked the girl, "Where are you from?"

The girl was very beautiful. She had a broad face, a fair complexion. She was wearing jewellery and shimmering clothes. She said "I am lost. Yesterday I got married. Today my in-laws took me to Hanuman temple. When we came out, I went one way and they went another way." She had been walking and walking. She dared not get into a taxi.

Just then, the wife of a noted cloth tycoon happened to pass by in a car. She stopped to check out the unusual situation. There was a newly married woman. There was my mother who was tall and strong. The cycles were also there. The tycoon's wife said, "I will send the car back for you. Please see her home."

Her car came back. My mother sent her cycle with one of the boys. The other boy rode in the car with them with his cycle at the back.

However, first the policemen took them all to the police station. After the report had been made, the policemen said they would see the girl home the following day. Mummy insisted that the girl be allowed to go with her. She told the policemen that her maternal uncle was a member of parliament. Upon hearing this, they began to mollify her. My mother insisted that she would accompany the girl to her parents' home. She told the policemen, "You know, if this girl stays even one night here, her honour will be lost. I am not saying you are bad, but it is the public view that any girl who has spent a night at the police station is not worth anything anymore."

Two policemen accompanied my mother and the girl in the car. The student and his cycle went too. Mummy's voice lowers as she retells the story. "There were a hundred people sitting in her parents' small house. When they saw us, they were mad with joy. They started shouting, ‘The girl has been found. The girl has been found.' The in-laws were there too. I told them ‘I have come with this girl to tell you personally that nobody has touched her. This girl is as untouched and pure as she was before. Now please look after your girl.' "

They began to prostrate themselves at my mother's feet, calling her "Goddess, Goddess." Even the girl said, "For me the goddess appeared. For me a goddess appeared." My mother was very satisfied that she had been able to do a good deed.

She came back home to find everybody was asleep. There was no food or water left for her. My mother says, "I went to sleep too. The next morning I told your father I came home after midnight, and he was angry and said, ‘Why take an unnecessary risk?'"

My mother began attending M.A. classes at the University soon after she completed her "full" B.A. in 1955. The Master's was a joy compared to the B.A. Her knowledge of the scriptures became an asset as she was studying classical devotional poetry.

The emphasis now was on getting a first division, something that had eluded her all her life. After studying for two years, in the preparatory holidays before the final exam, she developed a severe pain in her right arm and had to defer taking the exam.

By that time, her 28-year marriage had disintegrated. My father left for his clinic and did not return home. I was 12. Most people thought it was my mother who had left her husband to study and live her own life. A failed marriage, a husband who had left home, was such a disaster that the fact that I had lost a home and a father was never discussed. It was not something I myself talked about fully for over 40 years.

Ranjan says the trouble had begun when Mummy decided to take the first tuition at Miranda House. My father's earnings had begun to slip. My mother says she had no choice but to go out and earn some money. Unlike their life in Rawalpindi, there was no grandmother here who would pay for the housekeeping, or familiar traders with whom they could run up credit. The military life too was finished.

Lata was completing her B.A., Ranjan was in Year 10 and I had not gone to school as yet. Mummy thought, how long can one depend on relatives? She says: "Life ahead looked very dark. Only Swaran was my support. He would sign a cheque and leave it with me. In between, he would give me money. But in the life ahead, only I could do something. I had energy, enthusiasm and intelligence. Only if I stood up would I be able to look after my children."

Ranjan says: "Once she started giving tuitions, she wasn't asking Pitaji's permission whether she could go to another college. Then she started studying in order to teach. The result was that not only was she earning more money, but she also was not there. Pitaji would come home and eat his meal alone, spend the afternoon alone, spend the evening alone. We were busy with our colleges. Pitaji was lonely. So when she came home, Pitajei had no sympathy for her. He had his own problems."

For my father, life fell apart after Partition in 1947. He was no longer the breadwinner.

Mummy's income kept increasing, his income kept decreasing. Mummy wanted kindness. Pitaji wanted obedience and recognition that he was the husband, the lord and master. But now his word was no longer unchallenged. For Pitaji, his years in the army were the brightest portion of his life. He talked continually of what the commanding officer had said to him.

But everybody else had moved on. His world was slipping.

Ranjan remembers that the household was still there but cracking when I was nine. She left on a scholarship to Sarah Lawrence College. The fights between my mother and father increased. For a short time, on weekends, the three of us would play 'Cut Throat' - a three-handed version of Bridge - in the bedroom. My mother would bluff outrageously and often win. My father would get angry that she had not followed the rules, she had not played it right, and she still won. One day he said he was going to play no more. Thus the only kind of activity we enjoyed together stopped.

There was no longer any laughter at home.

THE GRADUATION PHOTOGRAPH

Mummy's black and white graduation photograph used to hang on the whitewashed wall in the living room of her house along with Nanaji's photograph. It shows my mother in a sombre pose, wearing a sari, holding her Master's degree in Punjabi literature. She is standing under some trees, so it looks as if a few leaves are sprouting from her head.

Three years after her death in 1996, I took this photograph to her summer unit in Dharamshala, which is now my base in India. I placed it beside the other family photographs on the covered tin trunk. For me this photograph told the epic story of her life. All the years that I lived with my mother, education was at the centre of our lives - hers and mine. There was never the slightest doubt in my mind that the excellence we were striving for was excellence in learning.

But parallel to the story of my mother's education was another story.

At her graduation ceremony in the University of Delhi in 1958, she was alone. Our family home had dissolved. My father had left home and was living at his clinic. My mother was living at the Working Girls' Hostel. I was in the hostel in Queen Mary's School in Delhi. Lata and Ranjan were already married and living in Bombay and New York respectively. But for us in Delhi, the traditional structures had fallen away.

There however was time for philosophy and poetry. It must have been 1957 when Mummy went to the Miranda House hostel to prepare for her Master's degree. She was 46. Her room was on the first floor, on the eastern side of the quadrangle. There were friends with whom she discussed Punjabi and Hindi literature, the philosophy of Sikhism and Hinduism, the Bhakti movement.

These discussions took place over hostel food that came from the mess in a three-tiered container eaten with rice jazzed up with cumin and ghee on an electric stove in Krishna Sharma's hostel room.

My mother had become friends with Krishna Sharma. She was a historian and went on to do a doctorate on Kabir and the Bhakti Movement. My mother knew Kabir's work for it is incorporated in our Scripture, the Guru Granth Sahib. Not only did they discuss poetry, history and religion, but Krishna Sharma also found in Mummy a surrogate mother. She was the first person who said to me that my mother was remarkable, that she had courage, that she was a scholar. Krishna Sharma was my mother's first public fan and would say over and over again that I was fortunate to have a mother like her.

But that was the only mother I knew and I did not regard her as unusual.

My weekend visits to Miranda House when I was 13 were also my first experience of being with someone who was not from North India. My mother's neighbour in the hostel was a South Indian woman who had been married and widowed as a child. Listening to her tell Mummy of her struggles to obtain an education and financial independence first brought home to me that the stories of women in India had a common thread of sorrow. I listened to her, for I was always in the room as that was the only place I could be.

One day, the South Indian neighbour's uncle was visiting her. The story about him was that he had received a boon from a yogi or fakir and could read hands accurately. In his family he was much avoided for he had the habit of telling people what they did not want to know. But my mother was taken by the idea of this uncle, and wanted to know, more than anything else, whether she would get a first division in the coming M.A. exams.

The uncle looked at her hand and told her, No, she won't get a first division. But, he said it wouldn't make any difference because she would get good jobs. Mummy says he looked at her hand, then looked up at her, and said softly, "Life has been difficult." But, he said, the last 20 years of her life would be her best years.

And so they were. She retired from academic life at 75 after being the founding principal of three women's colleges in Punjab.

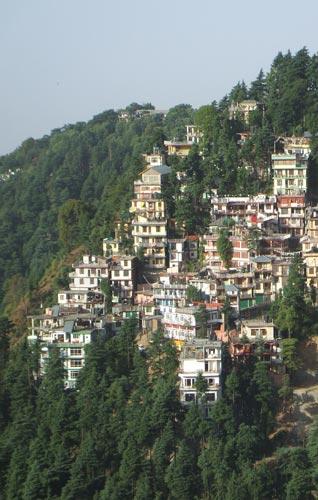

DAWN IN DHARAMSHALA

I sit in my mother's house in Dharamshala seeing the outer Himalayan ranges glowing in the early morning light. The glow suffuses the low lying peaks on the right, slowly moving westwards. After an hour-long display, the sun emerges suddenly from behind the mountains.

My mother sits on her high divan bed saying, "Shukar hai, shukar hai." How do I translate this? Thankfulness is what it means, thankfulness from a grateful heart. To how many is it given to wake up to a view of the Himalayas?

Dharamshala is my mother's special place, the bit that belongs to her alone. She loves the sight of the mountains. They remind her of the summers she spent as a child in Murree, near Rawalpindi, when she would run all day among the hills till she could hear the servants calling for her. She has used it as a summer place since 1977. After she retired because her eyesight began to fail, she spent nearly half the year in Dharamshala.

Her identity in Dharamshala is focused on religion and family, rather than education.

For a while, people knew her as the Patti Principal, referring to her last college in Patti, near Amritsar. But towards the end, before she died in March 1996, she was known simply as Mataji (Mother).

She sits on her bed, holding court among her many visitors, dispensing advice to all who came. And then the common refrain 'shukar hai, shukar hai'.

To how many people is it given to have a place of their own and the means to live with freedom and dignity?

People begin streaming in as the winter sun moves towards my mother's unit. When one lot goes, another group comes, and my mother says, "Come, come. Blessed is our fortune that you have come. I haven't seen you all day. Come, come. Let us have tea."

Swarna, 16, from the nearby village who helps in the house, begins to brew the tea with milk, cardamom and sugar. "Bring out the dry fruit," she says.

Before one neighbor leaves, another comes. "Come in, come in, welcome," my mother chants. "Put the tea on," she tells Swarna. "Come, come. Sit, sit. You make my heart feel glad."

Some come to see me to honour Mataji, and also to check out this Australian daughter from Melbourne. The litany begins. When did you arrive? Where do you stay?

But soon the conversation goes back to the familiar tracks - life in Dharamshala, births, marriages and death, matters of religion. The visiting does not stop at night. Even when the electricity goes off, there are visitors, for every house has candles on hand. This is, of course, a time before the neighbourhood got colour TV and cable.

In the early morning and late at night when we are alone, she talks of her thankfulness that she can hear so acutely. "I pleaded with God," she says "to let me continue to hear so that I could hear His name." The scriptures she already knew in her head - the result of a lifetime of religious devotion and a critical study of religious poetry for her Master's degree in Punjabi literature.

Each time we meet, it is a time to count our blessings. We re-establish the small talk that cannot be communicated by letter or phone. Also to say the things we cannot say to anybody else. I tell her of my joy at completing my Ph.D and going back to a life of learning and scholarship. As she doesn't think she can make the 14-hour flight to Melbourne, I describe my house high on a hill, with its cathedral ceilings, the 100-year-old wood inside and outside the house, looking out on a forest of eucalyptus trees. I tell her of my delight in the large rolling garden - the yellow wattle along the drive that makes winter a blaze of yellow, the white and mauve agapanthus along the driveway and a cascade of yellow jasmine falling over the rock wall. I describe to her the smell of the eucalyptus after the rain, the sound of the wind chimes hanging outside the kitchen.

I tell her of the birds that came every day, often the only visitors. I tell her of the plum trees and apricots, nectarines and peaches, lemons, olive and quince, so that she can re-imagine the orchards of her grandfather's house.

"I am waiting for death," she says. "I am waiting at the station, but the whistle does not blow." We collapse into laughter. This is something she cannot choreograph.

"That's very well for you," I say, "but what will happen to me?"

"The spirits look after those they love," she says.

"Well, in that case, here is my wish list for when you have greater power to deliver," and we laugh again.

My mother dies three months later at 85, after a brief illness. Ranjan and I go to Dharamshala to hold the Akhand Paatth, the three day reading of our Scripture.

One by one, Mummy's neighbours and friends come, not to commiserate with us in our grief but to mourn her for themselves. People stream in to talk of my mother. All of them say how she had loved them in a special way, how she was the mother or sister they had never had.

They do not talk of her achievements. They talk of the love she had given them. They are the chief mourners, we the outsiders. "Don't think," one of her neighbors says, "that if you had not come to hold the prayers, there would have been no prayers said for Mataji."

And in the overflowing hall where prayers are chanted for three continuous days and nights, the congregation folds me in for I am my mother's daughter.

This is the third and final segment of the saga of Sardarni Inder Kaur.

[Supriya Singh was born in India and moved to Malaysia at 23 when she got married. In 1986 she migrated to Australia. She lives in Melbourne and is Professor, Sociology of Communications at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT University). She has a son and grandchildren in Melbourne and a son in Kuala Lumpur. She continues to spend part of the Indian winter in Dharamshala.]

September 11, 2010

Conversation about this article

1: Gurinder Singh (Stockton, California, U.S.A.), September 11, 2010, 10:38 AM.

Supriya Bhain ji: Thanks for bringing back memories of Maasi inder Kaur ji. She was a great Sikh woman who affected many lives in a positive way. She stayed with us for a few weeks in Amritsar during her last days, before we took her to a nursing home. We also had a chance to meet you after her departure from this world. We remember and talk about her very often. She is fondly remembered by many others who happened to know her. She was a great Gursikh who left lasting impressions in our life.

2: Inni Kaur (Fairfield, CT, U.S.A.), September 11, 2010, 11:54 AM.

Thank you for giving us glimpses into the life of a Gurmukh. Immersed in Naam, her fragrance lingers and will continue to inspire those who long to hear the Divine Melody within.