People

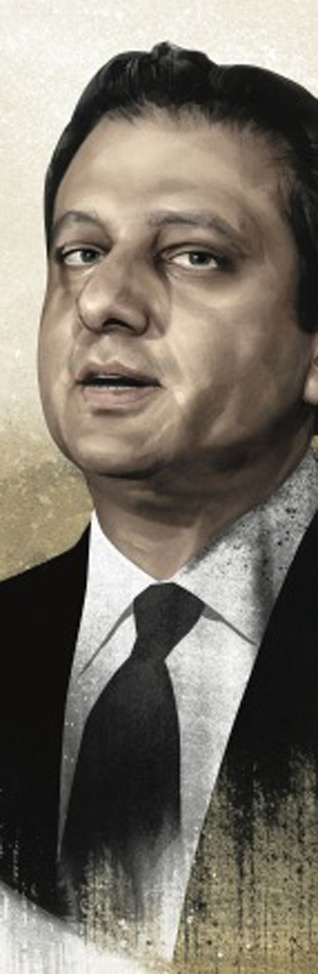

How U.S. Attorney Preet Singh Bharara Struck Fear Into

Wall Street

Part I

JEFFREY TOOBIN

As the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, Preetinder Singh “Preet” Bharara runs one of the largest and most respected offices of federal prosecutors in the country.

Under his leadership, the office has charged dozens of Wall Street figures with insider trading, and has upended the politics of New York State, by convicting the leaders of both houses of the state legislature.

Last week, he announced charges against a hundred and twenty alleged street-gang members in the Bronx, in what was said to be the largest gang takedown in New York history. The turning point in his own career, though, took place not when he triumphed in a courtroom but when he masterminded a dramatic congressional hearing.

Preet Singh Bharara, who is now forty-seven, graduated from Columbia Law School in 1993, spent several years at private firms, and then, from 2000 to 2005, served as an Assistant U.S. Attorney (“AUSA“), in Manhattan. On leaving his A.U.S.A. post, he made an unusual choice for a promising young lawyer. Instead of becoming a partner at a law firm, he went to Washington to work for Senator Charles Schumer, the New York Democrat.

Schumer chaired the Judiciary Committee’s oversight subcommittee, and Bharara was the top aide on his staff. He organized hearings and prepared Schumer for conducting them. Schumer is famous for cultivating media attention, and his aides are responsible for making sure that he gets it.

“When Chuck approaches a hearing, he wants to elicit something, leave a mark, unearth something that the Associated Press (“AP”) will file a story on,” a Schumer staffer from this era told me. “Preet knew this, and he would take the pen and make the first draft of questions that made Chuck’s round of questioning stand out. He would draft them with sound bites in mind. He learned to think that way and write that way.”

In early 2007, Bharara, under Schumer’s supervision, was investigating the firing of several U.S. Attorneys by Alberto Gonzales, the Attorney General in President George W. Bush’s second term. For a hearing on May 15th, the issue was whether the firings had been politically motivated.

Bharara prepared James Comey, who had been Deputy Attorney General in the Bush Administration, to testify.

“That was my hearing, chaired by Senator Schumer,” Bharara told me. He knew the witness well, because Comey had been the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District when Bharara was an A.U.S.A. there. “I talked to Jim the week before and said, ‘We’re going to have you come testify.’ ”

In debriefing Comey before his testimony, Bharara heard a more extraordinary tale than he had expected. On the night of March 10, 2004, Comey had learned that Gonzales, then the White House counsel, and Andrew Card, the White House chief of staff, were heading to a Washington hospital, where John Ashcroft, the Attorney General, suffering from gallstone pancreatitis, was in intensive care. Gonzales and Card wanted Ashcroft to reauthorize a government surveillance program that Comey and his staff had concluded was unlawful. Comey and Robert Mueller III, the F.B.I. director, raced, sirens blaring, to beat Gonzales and Card to Ashcroft’s bedside.

In a tense confrontation at the hospital, Ashcroft told Gonzales and Card that, since Comey was Acting Attorney General, the decision was his to make.

As Bharara recalled, “Jim told me the whole story on the phone, and the hair stood up on the back of my neck, because I realized what a significant story this was, and I was sworn to secrecy and nobody knew about it. I told Chuck. He was, like, ‘Whoa!’ ”

In the days leading up to the hearing, Bharara and Schumer told no one about the revelation that was coming. “I was afraid that if the story got out of what Jim was going to say the Bush Administration would figure out a way to prevent him from testifying,” Bharara said. “We needed to preserve the element of surprise.”

At the committee hearing, Comey, under Schumer’s questioning, told the story of the bedside confrontation. It caused a sensation in the hearing room and in the press. “Russ Feingold” - the Wisconsin Democrat - “said after that that it was the most amazing and jaw-dropping hearing he had ever attended as a senator,” Bharara told me. “So that was my formative experience.”

Less than two years later, when Barack Obama was elected President, Schumer recommended that he nominate Bharara as the United States Attorney for the Southern District.

Bharara was forty, and he brought a media-friendly approach to what has historically been a closed and guarded institution.

In professional background, Bharara resembles his predecessors; in style, he’s very different. A longtime prosecutor, he sometimes acts like a budding pol; his rhetoric leans more toward the wisecrack than toward the jeremiad. He expresses himself in the orderly paragraphs of a former high-school debater, but with deft comic timing and a gift for shtick.

Bharara’s success with Comey’s testimony prefigured some of the methods he has used as prosecutor. He believes in meticulous preparation and reveres the tradition of collegiality among current and former Southern District prosecutors, like Comey and like him. He also welcomes publicity.

The U.S. Attorney’s main office is housed in 1 St. Andrew’s Plaza, a brutalist carbuncle beside the Thurgood Marshall United States Courthouse, a classical-revival gem in lower Manhattan. Next to the door of Bharara’s office suite, there is a large-format photograph of a reunion dinner of Southern District prosecutors, at the Plaza Hotel, in 2014: hundreds of middle-aged white men in tuxedos. For decades, a stint as an A.U.S.A. for the Southern District has led to prosperous anonymity in the upper reaches of the legal profession, especially in major New York law firms.

And Bharara’s predecessors in the top job include Robert Morgenthau (1962-1970), who later became the Manhattan district attorney; Rudolph Giuliani (1983-89), subsequently the two-term mayor of New York; Mary Jo White (1993-2002), the current chair of the Securities and Exchange Commission; and Comey (2002-03), now the director of the F.B.I.

“At least since the time of Morgenthau, the Southern District has been known for integrity and innovation,” Jed Rakoff, who was a prosecutor in the Southern District before he became a judge there, in 1996, told me. “The Southern District was the first U.S. Attorney’s office to take on white-collar crime on a regular basis. It led the way in official corruption cases,” as well as in Mafia cases and in terrorism cases.

“There’s a tradition of independence in the Southern District,” Rakoff said. “And that has often led to tension with the Justice Department.” Indeed, in law-enforcement circles the Southern District is nicknamed the “sovereign district,” because of its reputation for resisting direction, even from its nominal superiors, in Washington.

Some have said, half-jokingly, that the Southern District is the only U.S. Attorney’s office with its own foreign policy.

In 2013, Bharara’s office charged Devyani Khobragade, then the Deputy Consul General of India in New York, with committing visa fraud in order to gain entry for an Indian domestic worker in her employ. Khobragade was strip-searched after her arrest, and the government of India demanded an apology and removed the security barricades in front of the U.S. Embassy in New Delhi.

Secretary of State John Kerry expressed regret about Khobragade’s treatment. Bharara told me that the case originated in the State Department, and was properly vetted by his office. (Khobragade, who still faces charges, has gone back to India.)

On a more positive note, in March Bharara’s office charged Reza Zarrab, a Turkish gold trader, with money laundering and with helping Iran evade trade sanctions imposed because of its nuclear program.

In Turkey, where the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has become increasingly authoritarian and tolerant of corruption, Bharara has been hailed as a hero on social media. He quickly gained nearly three hundred thousand Twitter followers, many of them in Turkey, and has had to decline numerous offers of Turkish rugs and delicacies, though he did take his son out for Turkish food.

Bharara’s family history is unusual for someone in his position. His parents were born in what is now Pakistan, before it separated from India. Brought up a Sikh, his father is Jagdish Singh, his mother named Desh; their families joined the great migration to a newly created India after the Partition of Punjab and the subcontinent in 1947.

“My father is one of thirteen, my mother’s one of seven, and that doesn’t count siblings who didn’t make it for very long,” he told me. The family eventually settled in Firozpur, in Punjab, where Jagdish, a physician, was assigned to the Indian railway system. Shortly after Preet was born there, in 1968, Jagdish received a fellowship to practice medicine in Buffalo. “My mother had never seen snow,” he said.

The family soon moved to New Jersey, where a second son, Vinit, was born, and Jagdish set up a pediatric practice in Asbury Park, with Desh as the office manager.

Vinit Bharara told me, “Dad was a principled, disciplinarian kind of guy, an introvert, very focussed on our values, cared a lot about our getting good grades. He doesn’t have a great sense of humor. Our mom was sort of the opposite. She is an incredibly optimistic, affable, easygoing person. She loves to throw parties and mingle and make friends. Preet and I both got that yin/yang.” (In keeping with the local customs of his adopted region, Bharara became a Bruce Springsteen fan and has attended about thirty of his concerts.)

Bharara recalled, “Our dad definitely wanted us to grow up to be doctors, but in seventh grade I read ‘Inherit the Wind’ and decided I wanted to be Clarence Darrow. And then, in tenth grade, chemistry was a disaster, and that probably sealed it for lawyer over doctor.”

After serving as valedictorian of his class at a small local private school, Bharara went to Harvard. A college friend, Viet Dinh, recalled that he met Bharara in an introductory government seminar. “Our first assignment was to determine whether the Framers set up the American government based on the idea that man was essentially bad or that man was essentially good,” Dinh said. “We left class and wound up talking all night. I argued ‘bad,’ and Preet argued ‘good.’ I am more skeptical. Preet is more optimistic.”

Bharara was a Democrat, and Dinh a Republican, who went on to serve as a senior official in George W. Bush’s Justice Department. Despite their political differences, the two have remained close friends. (Bharara was the best man at Dinh’s wedding.) “People think that because Preet is a prosecutor he sees only the underbelly of society, but he fundamentally believes in the goodness of man and that government can ennoble society,” Dinh said. “He sees all the bad, but he sees his job as a way to foster good.”

After Harvard, Bharara went to Columbia Law School. “My wife never wants me to say this, but I was not a good attender of classes,” Bharara told me. (Bharara and his wife, Dalya, a nonpracticing lawyer, live in Westchester; they have three children.) He figured he could read the texts. “I think the only class in which I had a perfect attendance record was trial practice,” he said.

A veteran of the Southern District taught the class, which fixed Bharara’s ambition to become a federal prosecutor. In 1999, Mary Jo White offered him a job as an A.U.S.A. “It was the best day of my life,” Bharara said. “It was awesome.”

Vinit Bharara followed Preet to Columbia Law School but, after practicing law briefly, became an entrepreneur. His first venture, which included Preet as an investor, did not thrive. Then he and a partner went into the diaper business. Preet, of course, became the U.S. Attorney.

He said, “I have subpoena power, I’m chief federal law-enforcement officer in Manhattan, Bronx, and six other counties. So I’m thinking I’m winning the family competition, and my brother calls me and he’s, like, ‘I’m going to sell diapers.’ I said, ‘Knock yourself out, man, I still got subpoena power.’ ”

Vinit’s company, diapers.com (“We’re No. 1 in No. 2”), went on to be acquired by Amazon in 2011. Preet told me, “That’s my brother’s way of saying, ‘Hey, bro, I see your whole U.S. Attorney thing, and I raise you five hundred and forty-five million dollars.’ ”

Southern District prosecutors traditionally conduct roasts of departing colleagues. When Richard Zabel, Bharara’s longtime deputy, left the office last year for the private sector, Bharara sang a farewell to the tune of “American Pie.” In his response, Zabel said, “Since I left the office, everyone has been asking me the same question. Have I seen ‘Billions’?”

The television series, on Showtime, features the pursuit by an aggressive U.S. Attorney, played by Paul Giamatti, of a Wall Street billionaire for insider trading. It is widely thought to have been inspired by Bharara’s long-term investigation of Steven Cohen, the founder of SAC Capital Advisors; there is also a fanciful subplot involving sadomasochistic sex.

“The truth is, I haven’t seen it yet,” Zabel said. “But I did see a clip, where a woman in a dominatrix outfit stands astride our shirtless U.S. Attorney, burning him with a cigarette and then urinating on him.” Zabel added, “I am surprised how since I left they have lost control of his image.”

Before Bharara became known as the scourge of insider trading - a 2012 Time cover story called him the “top cop” of Wall Street - he gained attention for the cases he did not bring against the financial industry. He took office in 2009, at the height of the mortgage crisis, and the Southern District, along with the Justice Department, in Washington, conducted investigations of the major firms and individuals involved in the financial collapse. No leading executive was prosecuted.

Bernie Sanders, the Presidential candidate, says in his stump speech, “It is an outrage that not one major Wall Street executive has gone to jail for causing the near-collapse of the economy. The failure to prosecute the crooks on Wall Street for their illegal and reckless behavior is a clear indictment of our broken criminal-justice system.”

In a conversation in his office, Bharara rejected the critique. Without going into specifics, he said that his team had looked at Wall Street executives and found no evidence of criminal behavior. “It shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone that the things that we had either been assigned before I got here or had the initiative to look at were looked at really, really carefully and really, really hard by the best people in the office,” he said.

“There’s a natural frustration, given how bad the consequences were for the country, that more people didn’t go to prison for it, because it’s clearly true that when you see a bad thing happen, like you see a building go up in flames, you have to wonder if there’s arson. You have to wonder if there’s anybody prosecuting. Now, sometimes it’s not arson, it’s an accident. Sometimes it is arson, and you can’t prove it.”

Eric Holder, who, as Attorney General, was Bharara’s boss for six years, made a similar point.

“Do you honestly think that Preet Bharara and all those hotshots in the U.S. Attorney’s office would not have made those cases if they could?” he said. “Those are career-making cases. Those cases are your ticket. The fight would have been over who got to try them. We just didn’t have the evidence.”

Continued tomorrow …

Jeffrey Toobin has been a staff writer at The New Yorker since 1993 and the senior legal analyst for CNN since 2002.

[Courtesy: The New Yorker. Edited for sikhchic.com]

May 3, 2016