Fiction

Emperor:

Duleep Singh & The Company

Chapter VI

A Serialized Hiistorical Novel by T. SHER SINGH

Previous and subsequent chapters are accessible by clicking on the DAILY FIX icon on the HomePage.

CHAPTER VI

At this time, Lord Auckland had other worries as well.

Interspersed with meetings on the developments in Punjab, there was a string of conferences with visitors from Shanghai and Hong Kong.

It was work and work and work everyday; I could see he had a lot on his mind.

I was relieved when he announced, only a few days after the visit to the great banyan tree, that he wanted to take another group for a day’s visit to the gardens. It would give him some respite.

Imagine my surprise then, as I followed the group through the thickets beneath the tree, that he was going through exactly the same routine with them.

Except, this time around, he wasn’t talking about Punjab. “Imagine,” he said to them, “that this great tree is China …!”

I was gradually beginning to get a feel for what his Lordship had meant when he had said to me once that his work was nothing but helping a company do trade.

I remembered how, when we were making our way back from Simla for Calcutta only a few weeks ago, we had lingered for a few days longer than usual en route in the ancient city of Patna.

It was a memorable stop for me. Lord Sahib was tied up in some business, and he allowed me to sneak away for a few hours. I told him I had long wished to visit a cherished church of my faith that I knew stood somewhere nearby in the neighbourhood.

No ordinary gurdwara, it was.

It marked the site of the birthplace of our Tenth Master. When I got there, I was delighted to see a magnificent new structure … I was told it had newly been built with a generous purse the Emperor Runjeet Singh had granted them only a few years ago.

The small entourage of my assistants who accompanied me, all decked in the Latt Sahib’s livery, attracted a lot of attention. The locals held a special prayer service in our honour, and regaled us with sweet kirtan, followed by a sumptuous langar. I made a mental note: next time we are passing through, I must bring his Lordship here. He’s always been so curious about my Faith.

I felt blessed … my parents and all in my village would envy me when they would hear that I had actually visited this blessed site.

Heading back to camp, I was able to enter the Factory -- that’s what the locals called it, the Company Factory -- from its south-eastern entrance. I hadn’t given it much thought when I had left the camp on the opposite side that morning, riding by the huge wall that lined the road, it appeared for ever, until the road swung to the right and we entered the heart of the city.

I asked the others to continue to the camp where I would join them later. I walked into the complex. A cluster of munshis and babus -- clerks -- followed me as I entered the building, and saw my jaw drop as I stood there, frozen and speechless.

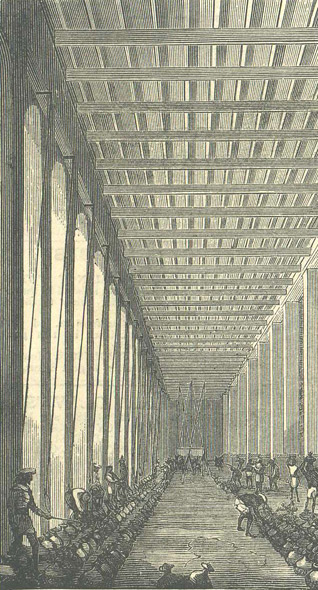

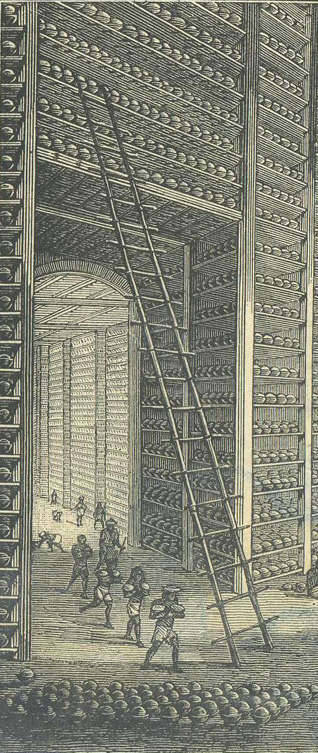

It appeared the wall I had seen along the road was one of the walls of the building which ran the whole length of the edifice. It was a structure larger than anything I had seen in my life. Higher than the walls of Fort William, bigger than the fort in Firozepur, no, even the buildings in the fort-palace of Lahore.

I couldn’t even see the far end … it would have to be stretching a mile, I guessed, but all of it within the same building.

Coolies were swarming inside, going about strange tasks. One of the munshis crept up to me and asked if he could be of help. I could barely understand more than a few words he was saying. I think he was speaking in one of the Hindu dialects. I had learnt a smattering of the poorbia (eastern) language by this time, and tried a few words on him. Another munshi pushed past him and said a few words. I could understand him better.

He explained how the product would be shipped in by boats from up country. I had already noticed the river running alongside -- the Ganges -- and at least a hundred boats docked outside, before I had entered.

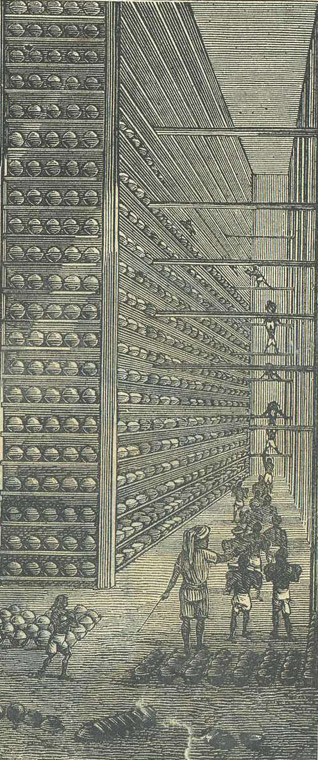

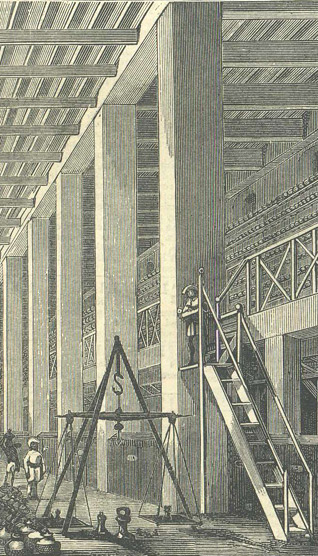

Inside the factory, the munshi went on, the product was processed and prepared for the market. First, it had to be dried, then rolled into balls of three to four pounds each. Wrapped in leaves. Stacked inside chests, about 40 to each. Put into storage in their godowns. To be taken carried out later to the boats on the backs of coolies, to be transported to Calcutta. From there, they were shipped to China and Europe.

Thousands were employed in the whole process. And, the munshi said proudly, we ship 12,000 of these chests every year. Sometimes more, depending on how good the crops have been that year.

Huge weigh-scales litter the endless halls. Floor to ceiling shelves are stacked with the balls. Rows and rows of shelves, some branching off into attached buildings at an angle from the main stretch. Ramps leading up to mezzanines, where further rows of shelves disappear into the shadows beyond. There are pulleys and ropes everywhere, with coolies climbing up and down like they’re on toddy trees.

“The Latt Sahib is happy with the work we do here?” He searched my face anxiously.

“What crops?” I ask, not willing to reveal my ignorance. This is the first I have seen or heard of such an operation.

“You don’t know, sir?” he was puzzled, looking up and down my uniform. “Why, opium, of course!”

“We produce opium here?” I asked, not sure if I had heard it right.

“Yes, sir!” he said, puffing his chest, “we are the suppliers of opium to the whole world!“

Suddenly, it began to make sense. The piece slipped right into place in the puzzle.

“We’re only a company doing trade, Amir Singh,” his Lordship had once said to me, “and I’m but a trader.”

The only thing that bothered me was the little I knew about opium -- ‘affeem’ is what we call it in Punjabi. It was a drug, wasn’t it? Addictive. Debilitating. Stupefying. Had my father been wrong in warning me against it, of telling me that it was not a thing a Sikh should imbibe.

Surely the Sahibs knew something we didn’t. Why else would they be shipping thousands of tons of it from here and selling it to the world?

* * * * *

I must confess the question rankled me endlessly, though I learnt to push it to the back of my mind and not let it distract me too much. I dared not ask his Lordship. It was not my place … I hadn’t forgotten: I saw nothing, I heard nothing. I was to say nothing.

I think it was a few years later … I was back in Lahore … I had been summoned by one of the Bhai Sahibs of the Court. It was Bhai Gurmukh Singh. He had questions relating to protocol: what the English Sahibs liked and disliked, their food preferences, what were appropriate things to say on their religious holidays, etc.

He was kind and gentle, and genuinely interested in learning. I thought he may not mind if I asked him a question or two of my own, pertaining to our faith practices. After all, he was a learned man. He would know and he would be open to my silly questions.

“Bhai Sahib,” I asked hesitatingly, “would you mind if I asked you something?“

His face was gentle, as he looked up at me. Not angry, not rushing, not dismissive.

“Yes, son, what is it?”

“Pardon me, Bhai Sahib, if you find it rude or ignorant, and please tell me to shut up if it is, but I am troubled by something. There are rumours that some people in court use opium from time to time. Some Sikhs, even. And I know that my employers trade in it and sell it to the world. Is it okay? Is it right?”

He smiled. He shook his head ever so slightly, and studied the carpet for a few moments.

“Sit down, son, pull up a chair. It’s a good question and I want to be straight with you.”

I grabbed a stool and sat down, close to his feet. I felt conspiratorial.

And encouraged.

“Sir,” I braved, “I hear even the Sarkar dabbled in it from time to time. Is that true?”

His face turned grim. Had I gone too far?

He didn’t say anything for a while. I thought maybe I should leave. I began to rise, but he put his hand on my shoulder and nodded.

“It is true,” he said. He waited a bit, and then continued.

“It is not right, it is not acceptable, but sadly, it is true. We, as Sikhs, are permitted no intoxicants, no drugs, not even tobacco. Nothing that is addictive. Nothing that dulls the mind and affects one’s judgement. Not even for recreation.”

He pulled up his left leg and tucked his foot under his other thigh, as he shuffled back a little in the settee and nestled against its back for support.

“But the Sarkar was susceptible to excesses. He had a number of vices, and we -- the three of us, the Bhais -- never minced our words in letting him know of our disapproval. To his credit, all-powerful that he was, he heard us out each time, and never expressed anger or impatience. He admitted he knew he was wrong. He promised he would try … but, then, he would falter again. A great man, an extraordinary man, but the lesser for his failings.”

His body rumbled as he let out a short laugh. He pulled up his shawl to cover himself tighter. I reached up and assisted him.

“But then, we all have failings. No one, not even the greatest amongst us are perfect. Therefore, we need to learn not to judge others, to be tolerant of the fact that they fail and fall from time to time. They fail us and they fail themselves. Just like each one of us.

“But he was gracious when we chided him. Allowed us to scold him. Even the good Fakir Aziz-ud-din joined us. The Sarkar was humble. That was his greatest strength.

“I remember once the Akalees -- his most loyal soldiers, but fiercely independent and committed to what they perceived as proper conduct for a Sikh saint-soldier, and always unaccepting of his excesses -- filed a complaint against the Emperor before the Akal Takht in Amritsar. The Jathedar sent him, the supreme ruler of the land, summons to appear in the court of the Akal Takht to answer the charges.

“And guess what? Runjeet Singh marches with his army to Amritsar. Once they arrive at the gates of the complex -- remember, it was his gift, it was he who had paid for the gilding of the building, so that it would be known as the Golden Temple forever thereafter -- he alights from his horse, asks everyone to wait, takes off his shoes, washes his feet and his hands, and walks alone to the Akal Takht.

“They try him for the misdemeanour. And find him guilty. The prescribed penalty is a dozen lashes. He bows before the Guru Granth, steps outside, removes his shirt, and stand with his arms wrapped around a tree trunk. No need to tie me down, he said.

“They gave him the lashes, and he took them without a wince.”

Bhai Sahib looked at me, to see if I had anything to say. I didn’t know what to say. This was all news to me. And too much for me to digest so quickly.

“Nothing … no position, no rank, no learning, no piety … allows anyone to bend the rules. The Sarkar never did. What we need to remember when we try and judge someone like him, is that we shouldn’t expect perfection. We can demand it, we should, of our leaders, but we know they will fail. We need to make sure that we don’t lose sight of their better qualities, their strengths, their sacrifices. While we don’t condone their excesses, we don’t turn blind to what they have done for the larger good. The test is: the failings should never be ones that prevent the man from doing his job, and that he indeed does what he is supposed to do.“

All of this was overwhelming for me. I have never thought of things in these terms. All I have done for much of my life so far is to steer away from judging what I see and hear. Is this going to mess me up? Get me thinking about things I shouldn’t get involved in? And lead to trouble?

“The problem,” Bhai Sahib continues … I want to stop him, but he carries on, as if in his own reverie. “The problem with potentates is the untrammelled access they enjoy to every excess. Anything, everything, is available for the asking. No, it is brought to them, unasked. Temptations galore, a thousand times more than what you and I grapple with.

“They are not saints. That is not the prerequisite for the tasks they take on … to feed and protect an entire populace. The saints don’t want to dirty their hands in these worldly tasks. You and I worry about our meals, our families, our homes, our futures. Runjeet Singh, because he took his role seriously, worried about all of us, the millions of us. And took care of us. It is no justification, and the good Lord knows I do not condone it in the slightest, but the magnitude of what we ask them to do, or what they ask of themselves, creates distortions in them as well. Immense appetites. And terrible excesses.

“But,” he said, and he raised his finger to emphasize the point, and wiggled it in front of my face, “if you’re not a Runjeet Singh, you don’t even have an excuse.”

“But then, why do the Sahibs trade in it?” I asked.

“Simple. Because there’s untold wealth to be made from it. People will pay a lot to feed their vices. So, if you have the wherewithal to do it, you build your markets by cultivating the vices … and you become the supplier. Even better, if you can, you make sure you become the ultimate and sole supplier.”

“Is that what they’re doing?”

“That’s what the Company is doing, and everything the Company does is to nurture that trade. They’ve just fought a war with China. You see, the Chinese know the ills of this weed and they’re anxious to control its sale. The English don’t want to let go of their monopoly. And they want a free and open market for their product. The product, that is, that is sold by the Company.”

“But they say it is sold to the Sahibs in England too. Is that true?”

“Yes, its true. There’s no morality involved in this whole affair. Trade, they tell us, is an amoral activity. If it makes profit, it is good. If it doesn’t, it is bad. If it makes a lot of money, it is very good.”

“But why do the English let it be sold in England, then? Doesn’t the Queen object, as have the rulers in China?“

“No, they don’t, because the Company hasn’t told their own people of the evil of opium. If they did, no one would buy it. And their goal is straight-forward -- to sell as much as they can grow and sell.

“One of your own Sahibs told me this. Here’s what they did in their homeland. In England, they distributed free samples so that English men and women would not hesitate to try the wonder drug. Doctors promoted its calming effect. Taught their patients to self-administer it to handle stress or sadness. Encouraged mothers to use it as a tranquilizer for their infants. Made it easily available as a tincture. Gave it a medical name: ’Laudanum’, they call it there.”

I sat there, now utterly confused. Should I believe this man, or should I rest assured that the Sahibs couldn’t possibly do no wrong.

“One more thing,” Bhai Sahib brought me back from my troubled thoughts. “How do you think the Sarkar got into this terrible thing. Sure, it was around, we knew about it. But we knew it was the crutch of unsavoury characters, that it is what drove them into infamy. Some used it, but for escape, and were openly derided for it.

“Then, along came a whole string of doctors. English doctors. Sent graciously to Lahore by our friends in the Company across the river ... to help, they said, as well-meaning neighbours. Our hypochondriac Sarkar, with his many ailments, received them. Ever curious but always suspicious and sceptical, he refused to take their prescriptions. He didn’t trust them. But they had one bit of advice: try opium, they said. We use it in England all the time. Even our women, our children, everybody. It relieves you of pain. Gives you comfort. Makes all ills disappear.

“The Sarkar knew of it. We all did. With the endorsement of the Sahibs, he turned to it. And, like many in England and China, he too fell under the charm of its addiction.”

He looked pensive, as he rearranged the shawl around him. Then, pulled out his leg, lowered it, and brought up the other to tuck under him.

“They didn’t tell him, though, that opium had one more quality … it could cover the taste of poison, hide the symptoms of poisoning.”

I had no idea what he was getting at. I looked at him, blank-faced, feeling that all of this was way above my head. I should be more careful asking questions in the future and not get into things that were none of my business.

“And … and,” he looked at me long and hard, “and you do know, don’t you, the fate of Maharaja Kharak Singh? Of the role opium played in his life … and in his death?”

To Be Continued ...

December 9, 2012

Conversation about this article

1: Baljit Singh Pelia (Los Angeles, California, USA), December 11, 2012, 10:35 AM.

On my visits to China over the last several years I have seen huge factories, owned primarily by the West, go up. They produce 'Apple' products and other gadgets the whole world craves but cannot otherwise afford. The fascination and addiction to these is widespread. The claimed benefits of their use is research and education. The reality is most of the younger generation abuse these to go astray and lose their bearings and connections to their religion, culture and proud history. The privileged ones breed a culture of corruption to afford these for showing off their high status or ill-gotten wealth. The immense profits generated are siphoned off to the west, along with the brightest minds that can also be procured and used as a human resource which we generally refer to as immigrants and aliens ... And thus the 'Company' lives and continues to thrive.