1984

Labh:

A Tale Of Resistance To India’s State Terror -

Part V

RATTANAMOL SINGH

Continued from last week …

PART V

A few days later, Devinder received a message: “Bhaji is going to Pakistan. Meet him at the Darapur Bypass and bring Rajeshwar.”

It had been a while since Sukhdev had seen Rajeshwar, and in Kashmir he had mentioned how much he missed his eldest son.

That night, Devinder arrived at the instructed location where a boy quickly approached her. “Chalo, chalo, we’re late. You just missed him. We have to go.”

It was dark now, and off in the distance Devinder saw two men board a departing truck. Devinder is certain one of them was her husband, and she tells us, “We definitely saw two people entering the truck, but we didn’t meet him.”

Unable to meet Sukhdev, they returned home.

It was a long night, and Devinder did not sleep. In the morning a police jeep came and took Devinder’s eldest brother. Devinder and her mother were both frustrated. They had no idea why the police took him and were debating who to contact in hopes of getting him released when another police jeep stopped in front of their house.

An officer named Jaswant Kahlon politely asked Devinder to get into the car. Devinder hesitated at first and asked, “Where’s my brother?”

“I’m taking you to him.”

A frustrated Devinder got into the jeep. Officer Kahlon brought the jeep to a halt at the vacant field across from those petrol pumps. A large crowd had gathered, and as Devinder exited the jeep, the collective gaze of the gathering slowly shifted towards her. Kahlon and his fellow officers separated the crowd and led Devinder to a bloodied lifeless body.

She immediately identified the body as her husband.

* * * * *

Act 7 - Four Deaths & A Funeral

“It felt like the roar of their voices was going to tear apart the earth and the sky.”

There’s little known about what actually happened on the night of July 11, 1988. General Labh Singh’s death is one of the most transformative events of the Sikh insurgency. Looking into the events of that night means asking a set of uncomfortable questions:

Who orchestrated the murder of Labh Singh?

Who gained from his death?

What happened to the money from the Ludhiana Bank Robbery?

There’s a theory involving poisoned milk. One is more focused on the money trail following the Ludhiana bank job. Another questions who went where in the days following General Labh Singh's death. The common theme is some sort of betrayal. In the end, all that is known is that he was found in a field.

Joyce Pettigrew calls General Labh Singh “Punjab’s most legendary guerrilla fighter.”

In the years leading up to Labh Singh’s death, the members of the Khalistan Commando Force had unleashed havoc on the Indian security apparatus. They had taken out Indian Army Generals associated with the Darbar Sahib attack, targeted those maintaining military rule over Punjab and killed politicians who organized the massacres of Sikhs. In October 1986, Labh Singh himself had spearheaded a daring attack in which his soldiers blasted straight into the headquarters of the Punjab Police.

From the state’s perspective, they had taken out one of the leading members of the movement. Ten days after Labh Singh's death, Avtar Singh Brahma, the head of an allied group, the Khalistan Liberation Force, was also killed. Avtar Singh, like General Labh Singh, was another beloved folk hero of the Sikh resistance.

Within two weeks, the two most feared, respected, and loved commanders of the Sikh insurgency were dead.

* * * * *

July 12, 1988

As Devinder stood looking over the lifeless body, she heard a policeman ask, “Child, can you identify who this is?” Dazed, and adamant that she would not cry, she looked the officer in the eye and said, “This is the man you have been looking for.”

General Labh Singh’s arm was wounded and bloodied. Blood seeped out of the bullet wound in his chest. Devinder ran her hand through his hair. Even now it looked and smelled freshly washed. The nails in his hands were partially removed and dangled outside of his skin. His knees and feet were dirty. His kachhera and undershirt were both torn. He had a yellow colored saafa, and his gun and shoes were placed inside it.

The police officers claimed they saw him walking and ordered him to stop. Instead, he ran into the fields. An encounter followed, and he was killed at this location.

The story made little sense. First, any claim of an encounter was immediately rejected by the owners of the nearby petrol pumps. More locals rushed to Devinder and agreed.

“There was no encounter here. There was no shooting here.”

Next, other members of the police pointed out a lady in the crowd and told Devinder that Labh Singh went to her house intending to kill her husband because he was an informant. Lastly, the local Tanda Police had little idea how Sukhdev’s body arrived here.

Officer Kahlon who had brought Devinder to the site was puzzled and told her he could not understand how any of this happened.

It is certain that the government’s portrayal of Labh Singh's death is a complete sham. In an open letter penned to KPS Gill, the chief of the Punjab Police, local photographer Roop Tara shattered the police account of the General’s death and openly accused the Punjab Police of orchestrating a cover up.

Devinder was taken to a nearby police station where she demanded the right to hold her husband’s funeral. They then took her to where his post mortem was being conducted. Devinder grew weary at being carted around by the Punjab police from one location to another.

There was a huge gathering of protesters who had assembled outside this building. Just as they had accompanied General Labh Singh to his court hearing and marched to Ludhiana for Devinder's release, they now stood outside the building that housed his dead body and shouted jakarey, the Sikh battle cries of "Jo Bole So Nihal, Sat Sri Akal".

The police charged the protesters, and Devinder remembers walking into the building while hearing the clatter of the police batons overpowered by the even louder battle cries emanating from the crowd.

Word of General Labh Singh’s death spread like wildfire. Family and friends traveled from Panjwar to the funeral house in Tanda Urmar where Devinder told everyone her husband’s prophetic words in Kashmir that signaled his impending death.

Two memorials were conducted, one in Panjwar and one in Tanda. Large crowds from all over Punjab came to both via cars, buses, trucks, tractors, and on foot.

Uneasy at the uproar General Labh Singh’s death had caused in Punjab, the police closed off all roads and bus depots in an attempt to block traffic. Unable to get through, people started holding langars along the roads leading to the memorials. Once the services were complete and the police left, there was a massive rush of people wanting to pay their respects to their General's family.

The villages surrounding Panjwar had a special relationship with Sukhdev. They were proud of him for the things he had done and viewed him as their warrior. In 1990, Paramjit gathered the residents of the surrounding five villages, and together they constructed a home for Devinder.

The same year, Harjinder Singh Jinda’s family attended a ceremony for Devinder’s children. Here, it was decided that both families would go visit Sukha and Jinda. By now, Harjinder Singh Jinda and Sukhdev Singh Sukha were imprisoned in the central Indian city of Pune and due to be hung for the death of General Vaidya.

In a few weeks, the group arrived at the jail in Pune, where they were searched and seated. As Sukha and Jinda entered the meeting room, they first walked around to check for cameras or recording equipment. They threw everything aside, and upon seeing Devinder, they stopped and immediately fell silent.

Suddenly and in unison, they began shouting jakaray. The sounds of the Sikh battle cry, “Jo Bole So Nihal, Sat Sri Akal” echoed through the prison.

Even today, Devinder is spellbound and smiles in awe thinking of this moment. “It felt like the roar of their voices was going to tear apart the earth and the sky.”

Before sitting down, they motioned over a guard and told him, “We have guests over. Bring coffee.”

Sukha and Jinda recalled Devinder’s search for Jinda at the Ludhiana house, and they teased her about it. Each one claimed to be Jinda. "I'm Jinda", "No, I am", "Bhabi ji, do you even know which one of us is which?"

Jinda had not seen Devinder since she left the Ludhiana house. The duo was imprisoned since before General Labh Singh’s death, and both were overcome with emotion in trying to give their condolences to Devinder. They teared up. “You used to be our bhabi ji (sister-in-law), now you are the sister of the Sikh nation.”

Sukha and Jinda both reflected on General Labh Singh and told Devinder again and again how much they missed him. They believed that if General Labh Singh was alive, neither would have spent a single day in this jail.

The guard returned with coffee. Jinda grabbed it and upon realizing it was cold, threw it at the guard’s face while ordering him to go make more.

There was a certain command that Sukha and Jinda possessed both inside the jail and with those they met. At the time of their sentencing, the judge had asked if they wanted reduced sentences. They rejected the offer, instead announcing that they’d given up their lives the moment Darbar Sahib was attacked. They refused an appeal and quickly accepted their death sentences while shouting slogans for Khalistan. The judge was struck by their principled stand and grew affectionate towards the two, saying he had never met people like them before. It is said he was teary-eyed when forced to sentence them to death.

Jinda had been shot during his capture. Devinder told Jinda, “I want to see the leg you’ve been shot in.” He showed Devinder his wound and attempted to reassure her by running around while yelling, “You don’t have to worry. I’m fine.”

The bullet was still inside and skin had started growing over it. Sitting down he continued, “It hurts when I walk around a lot, and I feel it at night. Otherwise, I am fine.”

By then, the guard returned with his second attempt at making coffee. This one was better and hence not thrown at him.

Sukha and Jinda continued joking with Devinder. They told her they were having fun inside prison. Devinder asked them how their lives were inside the jail. “We wake up at 3:30 am and pray. We’re happy between ourselves. We’re allowed to see each other twice a week.”

The conversation navigated to the Ludhiana house and eventually to how everyone was now either captured or killed. As the family was leaving, Jinda told his guests about the proposals offered by the girls of Ghumar Mandi. “All of them used to ask Devinder when she was going to marry me off!”

Jinda now viewed the date of his hanging as his wedding day. He referred to death as his bride and General Vaidya, who had allowed for this, as his in-law.

With this mindset, Sukha and Jinda viewed their looming execution as a celebration and told their guests to “pass out sweets, and sing ghoria.”

Ghoria are wedding songs sung by the groom’s marriage party as they arrive for his wedding. In thinking about their hangings, “This will be our final marriage. When we are to be hung, we will kiss the ropes ourselves!”

For Sukha and Jinda, there was a revolutionary tradition that fortified this struggle for Sikh sovereignty. In a famous letter sent to the Indian President on the eve of their hangings, they reflected on the spirit of revolution, referencing the Punjabi trio of Udham Singh, Bhagat Singh and Kartar Singh Sarabha with Tolstoy, Lenin, Che, and Mandela.

At the Battle of Amritsar, those defending Darbar Sahib had revived memories of the jungle-faring Sikh guerrilla warriors of the 1700s, and now Sukha and Jinda documented a historical parallel of resistance on their behalf.

“The dark storm of oppression that is blowing over the Khalsa and the fire of tyranny that is burning it, must have touched at least a little, the soul of Lincoln, Emerson, Rousseau, Voltaire and Shakespeare because the people fighting for their freedom and sovereignty have the same blood flowing in their veins.”

This was an age-old struggle pitting pervasive power against hopeful rebellion and now Sukha and Jinda seemed the latest entrants into a guild defiantly seeking liberation through revolution.

Until his hanging, Jinda sent letters to Devinder accompanied by drawings and sketches for the children. Sukha and Jinda comforted her when she was sick. “We are praying for you. Take care of the kids.”

They emphasized how lucky Devinder was to have taken Amrit. “We’ve done all these things in our lives. However, our only regret will be that we haven’t been able to take Amrit.”

They would ask about their friends who were still alive and if her husband’s killers had been found. During his time at Pune Jail, Harjinder Singh Jinda would send letters, often accompanied by his drawings. He had great affection for "his nephews, Rajeshwar and Pardeep" and would send drawings which depicted them getting into a plane and visiting him at Pune Jail.

In Jinda’s last letter, he gave his final farewell.

On the day of their hanging, Jinda and Sukha’s families passed out sweets and sang the songs of celebration that they had asked for. Jinda’s mother would later recount to Devinder the uncontrollable emotion of singing songs marking the arrival of her unmarried son’s wedding day as he walked to the gallows, only to soon thereafter, wash his body herself before cremating him.

* * * * *

The Khalsa has upheld the belief that whenever death comes, accept it with joy. For this reason please tell all those warriors of the world bringing the fire of freedom not to let go of the challenge thrown by us. Let their bursting bullets become a lament on our death.

The rope of gallows is dear to us like the embrace of our Lover but if we are condemned to be the prisoners of war, we will wish bullets to kiss the truth lurking in our breasts so that the sacred ground of Khalistan becomes more fertile with our warm blood.

[Sukhdev Singh Sukha, Harjinder Singh Jinda]

* * * * *

Act 8 - Coming to America

“My life is good”

By 1992, Devinder’s health was deteriorating, and she had to undergo multiple surgeries. The Damdami Taksal used to pay for these, and Devinder recalls the head of the Taksal, Giani Thakur Singh, with much fondness and appreciation.

Devinder had finally started walking again when the police came for her. Under the command of a local inspector named Ashok Kumar, they took all of Devinder’s belongings. A local police officer Balwinder Singh Chabal told Ashok Kumar, “Let her be; she’s raising her children” and asked him to return her possessions. Ashok Kumar refused.

One night at the police station, the drunk Ashok Kumar boasted, “I’m going to kill Sukhdev’s family.” Hearing this, Balwinder Singh Chabal went straight to Panjwar and emphasized the need to get Devinder out of India.

“We need to save Devinder and her children’s lives. The kanjar (prostitute) is saying there’s no way he’s going to let them live. We have to get them out as soon as we can.”

A large sum of money was collected by family and friends to arrange for passports and visas.

On January 7, 1993, Devinder and her boys arrived at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York. Upon arrival, they were immediately detained by immigration. Eventually they were released and told that a hearing would be held in a few weeks.

News of Devinder’s arrival spread quickly through the New York Sikh community. Her husband and his exploits were held in high esteem here. The Gurdwara provided an apartment and Sikh taxi drivers came together to place aside a part of their monthly salaries for the family. However, Devinder declined their offer and asked if they could find her a job instead.

“I wanted my children to know that their mother worked to provide for them.”

The Sikhs hired a lawyer for her immigration hearing where the judge told her to apply for a work permit and place her kids in school. She was eventually granted political asylum in 1995.

In Punjab, no one knew where Devinder or her children were. Police inspector Ashok Kumar raided Devinder’s house in Panjwar, demanding to know her whereabouts. “Where is she?! Who took her?!”

Devinder’s mother was home. He grabbed her and took her into custody while placing notice that she would only be released when Charan Singh Lahoria presented himself to the police.

Recalling what happened next, Devinder is the most emotional she has been. She pauses often, is reflective, and visibly shaken.

Charan Singh Lahoria was brutally tortured. He was beaten senselessly, huge presses were rolled across his body, and he was electrocuted with sharp nodes. The police hounded him, “How did she get to America?” “Who took her?” “Why did you let her go?”

After a month of this brutality, Rs 110,000 were demanded for Charan Singh’s release. The money was quickly gathered and given. After this ordeal, it became nearly impossible for Devinder’s father to move or walk. And it was during an attempt to ride his bicycle to a nearby town that he collapsed and died.

Devinder was unable to attend the funeral.

Two Sikhs who worked at a department store, National Wholesale Liquidators in Hemsted, Long Island, asked the store owner if he could provide Devinder a job. Devinder remembers him as a kind, caring Jewish man who told the two, “If she really is the wife of your general, then of course, I’ll help her too.”

Devinder worked at the store for 12 years. Her responsibilities included pricing and tagging incoming merchandise. The owner’s wife taught her English while explaining the process of opening merchandise and using a price gun.

“Bed sheets would come. This is a ‘queen‘; this is a ‘full‘; this is a ‘king‘. This is how we discount prices. She wrote down notes to help me remember what the new merchandise was. I would close the box of merchandise and tag it. Then, I would count all the inventory.”

Devinder started at $4.25 per hour. She worked well and received an additional 25 cent pay raise each year. Devinder is proud when she says, “When I left, I was making $9.30 per hour.”

Devinder thought it would be fun to work at the airport. She asked some girls who worked there if it was possible. They told her she needed to pass a test in English.

Devinder laughs as she recalls. “We used to memorize such large essays in school. Of course I could.”

She walks us through the application process. “I had to take a drug test!” Initially, she got 68% on her exam. She was feeling slightly down and thought of leaving it altogether. However, the urge to work at the airport persisted. So, she studied endlessly for 2 weeks, “I watched the exam prep on TV” and this time, “I got 96%.”

She worked at LaGuardia Airport’s Terminal 3 until June 2012.

By then, both her sons, Rajeshwar and Pardeep, had started working. Devinder is content when she says, “I worked and got both my children married.”

* * * * *

Currently, Devinder’s family lives in Richmond Hill, Queens, New York. It is a predominantly Punjabi neighborhood anchored by two gurdwaras and Punjabi shops and restaurants. Each year in July, she travels to Panjwar and organizes a huge remembrance on the anniversary of her husband’s death.

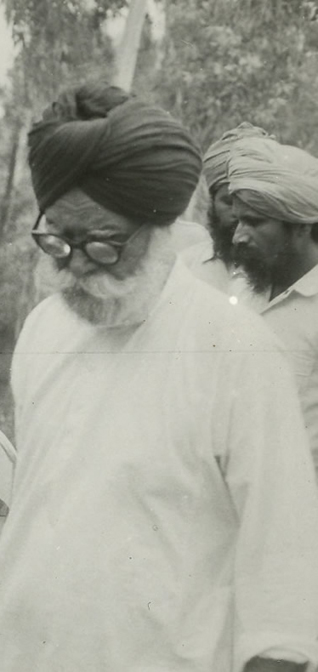

The first thing you notice walking into the house is a large portrait of General Labh Singh's lifeless body lying in that Tanda field. There’s another photo on a nearby wall of Devinder and Labh Singh on their wedding day. On the opposite wall, there’s a collaged picture of Sukhdev and his comrades standing dutifully behind Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale. It is as if the memory of the fallen general anchors the daily lives of the transplanted New Yorkers below.

Her house is in high spirits. Pardeep was recently married, and Rajeshwar’s wife gave birth to their second child.

“I am happy now. My life is good.”

CONCLUDED

Edited for sikhchic.com

August 26, 2015

Conversation about this article

1: Kaala Singh (Punjab), August 26, 2015, 2:28 PM.

This picture should shame every Sikh, a dead Sikh is lying on the ground and a crowd of Sikhs is watching and a Sikh policeman on the payroll of an alien entity probably killed this Sikh!

2: Kulvinder Jit Kaur (Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada), August 26, 2015, 5:03 PM.

Kaala Singh ji, this picture should shame the killers, not the Sikhs watching his lifeless body. Perhaps they came out of curiosity as to who this Labh Singh really was, the one that they read and heard about. Perhaps they were sympathizers who came to pay their last respects. There are many Sikh men in the Punjab police force. Not all are bad. People need jobs to feed their families! The Sikh policeman might be guarding the body as he was instructed to do by the authorities. We are too quick to point fingers. Just put yourself in those people's shoes and try to understand. I am curious as to what you would have done, Kaala Singh ji, if you were in their place? Not everyone is cut out to be a fearless "yodhaa." Most of us live our lives on the sidelines, living in quiet desperation ... or just passing comments! I remember you mentioned in one of your comments that you are not from Punjab. I guess you live in India but out of Punjab. You are one of the rare ones that takes so much interest in the Punjab issues, especially pertaining to Sikhs. Most Sikhs living outside of Punjab have a disconnect with the Sikhs living in Punjab as most of the issues don't effect them directly.

3: Talwinder Singh (USA), August 26, 2015, 7:57 PM.

Can't help but reading with misty eyes. Thank you, sikhchic.com.

4: Kaala Singh (Punjab), August 26, 2015, 10:56 PM.

@2: I have the experience of living both in Punjab and outside and I would humbly say that I know quite a bit about Punjab despite being a short time "settler" there. I do not agree when you say that people who live outside Punjab are not affected by the happenings in Punjab. You are right in the sense that Punjab having stagnated due to various reasons and having nothing to offer the Sikhs living outside Punjab does not figure much on their radar.

5: Kaala (Punjab), August 26, 2015, 11:23 PM.

@2: What I really meant in my comment #1 -- Is it not an anomaly that a person fighting for the rights of his people has do die at the hands of his own people, whatever the reasons may be?

6: Harsaran Singh (Denpasar, Indonesia), August 27, 2015, 1:37 AM.

After decades, it seems a lot could have been done for these young resistance fighters when they were hounded, tortured and brutally killed. But those were one of the darkest days in Sikh history. The situation for Sikhs in India post-1984 was the same as is for Muslims after 9/11. Those days a hostile Indian media projected every Sikh as a potential terrorist. Any one recalling those days will remember how difficult it was to travel in trains and public transport without getting suspicious stares from the public. Someone with a flowing beard or a kesri puggh was looked upon suspiciously. Moreover, by then Punjab had completely become a police state where fake encounters and custodial killings by the police had become routine. The government of India, in order to tarnish the image of Sikhs helped criminal and lumpen elements to infiltrate into the movement, therefore murder, rape, extortion and kidnapping for ransom became frequent. The Punjabi populace was in a real confused state. It was during this period that KPS Gill and company with active support from the Indian government indulged in one of the worst periods of human rights abuses ever recorded in Indian history. Under the garb of fighting insurgency they became perpetrators of a genocide against Sikh youth, intellectuals, academicians and religious persons.

7: Kaala Singh (Punjab), August 27, 2015, 3:08 AM.

@2: I missed your question about the "Yodha" part. My father owned a lot of land in West Punjab and during the Partition of Punjab in 1947, he lost everything and became a pauper overnight. He came to a newly created India and adopted a very frugal lifestyle and rebuilt his life from scratch, but did not kill for a living. In my mind he is the real "Yodha".

8: Kulvinder Jit Kaur (Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada), August 27, 2015, 1:20 PM.

@ #1. Kaala Singh ji, my reference to being a fearless "yodhaa" was specifically in context to the passive bystanders watching the lifeless body of Labh Singh, as seen in the picture. If people were feeling rage against injustice or remorse for not being able to do anything about it, they could not openly express it. Not everyone is bold and fearless to risk one's life and property by openly declaring their emotions. This is what I wanted to convey. Also, we should not expect others to do acts of bravery which we cannot do ourselves. You and I are at a safe distance, but people who live in the midst of this kind of environment are in a constant state of fear. I give full credit to all the refugees that arrived empty handed from Pakistan and built their lives again. They are no doubt yodhaas. They accomplished everything by sheer hard work.

9: Sunny Grewal (Abbotsford, British Columbia, Canada), August 27, 2015, 3:05 PM.

@2: Kulvinder Jit Kaur ji: The police officers who were collecting salaries while their colleagues were murdering and torturing Sikh men and raping Sikh women in jail cells are just as guilty as those who did these crimes. Please watch: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bKmxqqhlPD0. This is the story of a Sikh police officer who refused to participate in the killings of Sikhs. Not all of the "salary-walas" needed to show the same level of courage as Bhai Rajoana and Dilawar Singh, Sikh men who were police officers and sought to end the tyranny that their own colleagues had inflicted against their own community. Many could have shown the same courage as Satwant Singh Manaak and refuse to participate in the wholesale slaughter of innocent people. A paycheck is not a defense to genocide.

10: G Singh ( Arizona, USA), August 27, 2015, 5:18 PM.

Too bad KPS Gill is still living in luxury and has not paid for his crimes against humanity.

11: Kulvinder JIt Kaur (Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada), August 28, 2015, 7:24 AM.

@#9. My comments were all in reference to the picture and the comment about the people in the picture, including the police constable. I saw the Youtube recommended by you. Truly heart wrenching but also proves what I was trying to say. I am sure there were many other such police constables who felt the same way but did not have the courage to do what he did, i.e., leave the police force and expose the criminals in the police force and their atrocities on innocent Sikhs. To reiterate, the kind of torture Satwant Singh Manaak and his family were subjected to was a deterrent to many whistle blowers. All I was trying to convey was that we have to put ourselves in the shoes of these policemen, the good ones. Most of them come from rural areas with virtually no education and are very poor. They desperately need jobs to care for their families, to educate their next generation. This state of affairs of our rural Sikhs is a shame for our Quom. As I said earlier not every one has the courage of Satwant Singh. However, once the caravan starts moving, more and more will join it. As for the "equally guilty" we all fall in this category. Not many of us have exposed/talked about the injustices and atrocities on the Sikhs. Not enough have written about it. Not enough have extended help to the families of the victims. Collectively, we are equally guilty.

12: Harsaran Singh (Denpasar, Indonesia), August 28, 2015, 9:20 AM.

As I have mentioned in my earlier post, those were the most trying times for Sikhs, especially in Punjab. While most of the commentators acknowledge that these policemen desperately needed to keep their jobs, in the same breath they want them to have refused to follow orders or become whistle-blowers, which is a very naive argument. If you have studied the genocide of that period, you will know that KPS Gill had raised the infamous and dreaded STF (Special Task Force) out of the Punjab Police. This special unit was tasked with most of the extra judicial killings in Punjab. The STF people were mostly non-local policemen based in all district headquarters of Punjab. Their job was to pick up youth, torture them into false confessions and also eliminating those suspected to be involved in the movement, once the target was pointed out by informants or mischief makers. The policemen from the local police station had nothing to do with these operations. They came into picture after the killings, just for filing reports and disposal of the dead bodies (as the picture seems to indicate). Therefore, please do not make an issue out of something which was beyond the possibility of any human being, however courageous or virtuous he might be.